who decides the greatest film ever made?

An investigation into our industry's grand delusions.

Before we dive in, could I have your attention please?

My lovelies, we just hit 1200+ subs in 4 months (unreal) so it’s time for me to recalibrate (real). Mind taking the survey below to let me know what you’re enjoying so far, what you’d like to see more of & any other suggestions you may have? Thank you, i appreciate you all so much 🥹

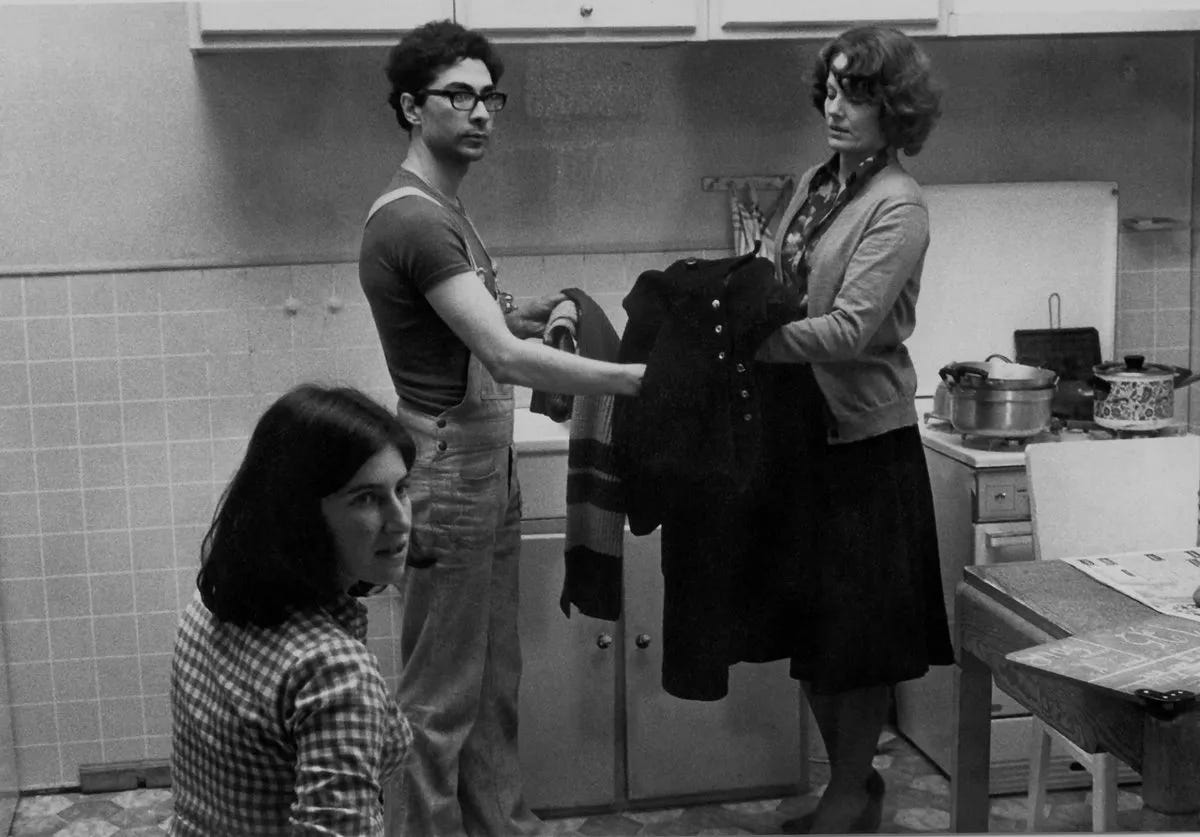

Earlier this month I found myself at the BFI Screening Rooms watching a widow make meatloaf for three and a half hours - and reader, it was transcendent. My second date with Jeanne Dielman came courtesy of a press screening for BFI's Chantal Akerman retrospective. The first time I watched it was on my laptop during lockdown, which felt thematically appropriate given the subject matter: a meticulous documentation of domestic imprisonment that makes Martha Stewart's daily routine look positively anarchic.

But witnessed on the big screen, Delphine Seyrig's Brussels apartment becomes a pressure cooker of repressed rage, each coffee grind and potato peel landing with the weight of a thousand feminist manifestos. A woman next to me gasped at the ending, a blessed first-timer. I caught myself envying her shock while simultaneously noticing details I'd missed before. Seyrig's hands betraying the tiniest tremor while folding that cursed blanket, or the way sunlight creeps through the apartment like an unwelcome houseguest.

Three years have passed since Sight & Sound's 2022 poll dropped this particular bomb into the canon. Their decennial survey had always served as cinema's version of the Vatican conclave - white smoke rises above London, and suddenly Citizen Kane (1962-2002) or Vertigo (2012) is blessed with cultural immortality. But 2022 brought reformation.

The British Film Institute, in a move that must have sent several lifetime Sight & Sound subscribers into the kind of existential crisis usually reserved for finding out your favorite auteur dated teenagers, flung open the voting gates to programmers, archivists, and academics. The resulting list didn't just put Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles at number one; it essentially announced that the old boys' club of cinematic greatness was now accepting new membership (dues payable in experimental film knowledge and feminist theory).

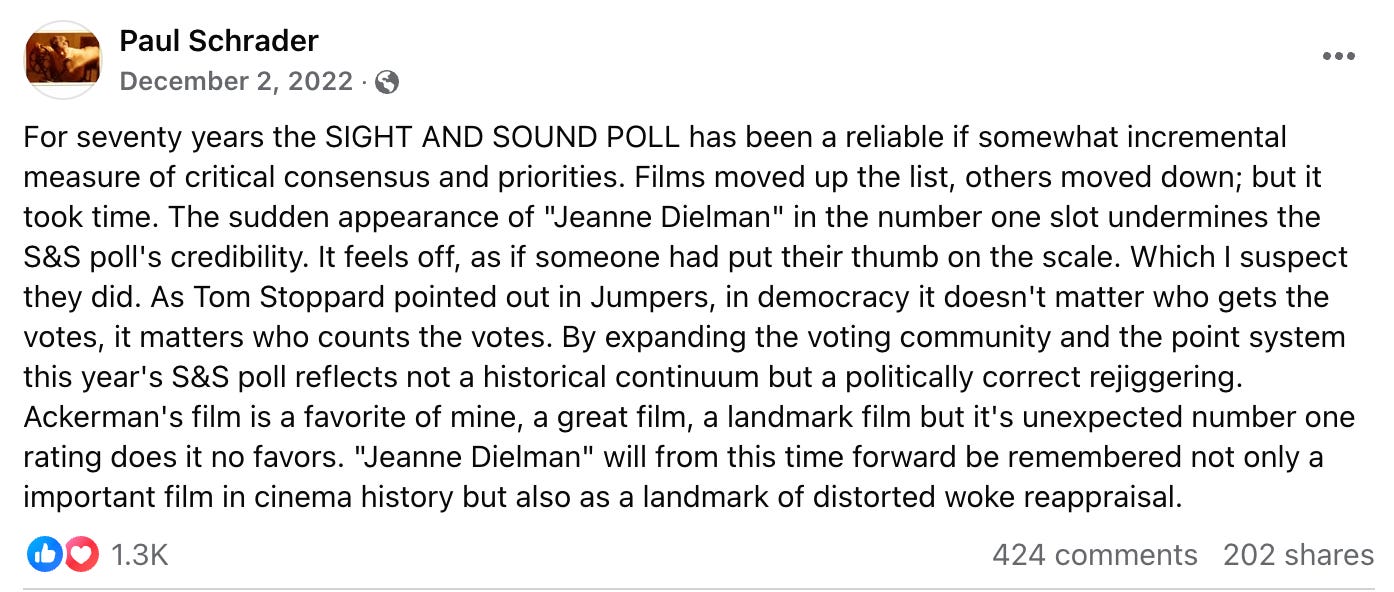

The aftermath played out exactly as you'd imagine, if you've spent more than fifteen minutes on the internet. Paul Schrader took to Facebook (a long-time concerning tradition) to suggest someone had "put their thumb on the scale" through "politically correct rejiggering" - a phrase that manages to be both dismissive and revealing in its defensiveness.

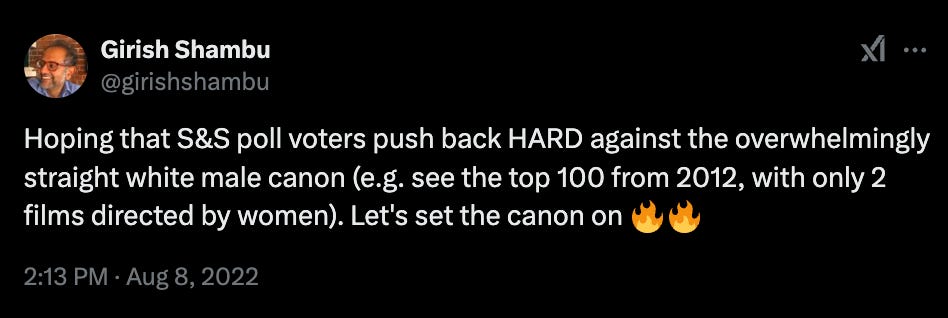

Meanwhile, management professor turned film theorist Girish Shambu celebrated the disruption of a canon historically anointed by white men imposing their version of "universalism" (a word that, in cultural criticism, usually means "things white guys decided were important in 1952").

The whole discourse revealed less about Akerman's actual achievement, a film so formally rigorous it makes Kubrick look like an improviser at Second City, and more about four fundamental delusions I believe we maintain about cultural permanence.

Great art means what it meant when it was made

Time makes fools of us all, but perhaps especially of film critics. I suppose this dawned on me somewhere between my first and second viewing of Jeanne Dielman, as I watched the same meticulous scenes play out in a radically different cultural moment. A film about domestic imprisonment hits differently (pardon the cliché) when you've actually experienced domestic imprisonment, just as a film about feminist rage lands with particular resonance when you've watched decades of progress disintegrate faster than a Twitter (rip) timeline.

Akerman made this film at 25, a precocious achievement that makes me question what I've done with my life besides running this cute lil’ Substack. Now her masterwork perches atop a canon that spent half a century treating experimental feminist cinema like that weird cousin nobody wants to sit next to at Christmas dinner, somewhere between Soviet montage's serious face and the French New Wave's cigarette aesthetics.

Schrader's lament about disrupting the "historical continuum" reminds me of those people who insist their hometown peaked exactly when they graduated high school. The notion that film history flows in some pristine river of influence - Méliès to Murnau to Welles to Hitchcock to Kubrick, with maybe a token Varda thrown in for diversity - belongs in the same dustbin as auteur theory and the idea that Tarantino's foot fixation qualifies as homage.

Cultural rupture becomes historical continuum becomes rupture again, an ouroboros of taste-making that would make Barthes reach for something stronger than his pipe. Two years later, I still watch critics scramble to contextualize Jeanne Dielman's ascension as either apocalypse or apotheosis, while the film itself sits there, accumulating and shedding meaning like the dust in Seyrig's immaculate apartment.

The strange alchemy of time transforms meaning whether we like it or not. In 1975, Akerman's film registered as a radical feminist statement about women's invisible labor. In 2022, it spoke to pandemic isolation, to lives measured out in domestic routine, to the quiet violence of confinement.

By 2025, with reproductive rights under siege and domestic violence statistics climbing, its climactic act of rebellion reads less like allegory and more like prophecy. This multiplicity drives the canonizers mad. They want stable meaning, fixed significance, a permanent hierarchy of artistic achievement. But art moves through time like light through water, refracting and splitting into spectrum.

The question "is this the greatest film ever made?" misses the point so spectacularly it almost circles back to relevance.

I find myself asking instead: greatest for whom? Greatest when? Greatest according to which version of ourselves - the ones we were, the ones we are, or the ones we're terrified of becoming?

The right room full of people can make anything immortal

Cultural canonization operates like an exclusive country club - one where the membership committee keeps insisting they're working on diversity while somehow managing to admit people who look remarkably like themselves. In 2022, the BFI approached this problem with all the careful choreography of a debutante ball, expanding their voter pool to over 1,600 critics, academics, programmers, and distributors. Their invitation letter invited voters to interpret "greatest" however they pleased. Maybe pick films "most important to history," or those representing "aesthetic pinnacles," or just whatever "had the biggest impact on your own view of cinema."

The path to cinematic immortality runs through what I'll call the Three V's of Validation:

Visibility (can people actually watch it?)

Volume (how many prestigious voices champion it?)

and Velocity (how quickly does it accumulate cultural capital?)

This unholy trinity determines which films get sanctified and which get sacrificed on the altar of availability. A film can't be canonized unless it's seen, discussed, championed, and - most crucially - made available for repeated viewing. Films that nail all three V's enter a kind of perpetual motion machine of prestige: they get preserved because they're important, and they're important because they've been preserved.

Meanwhile, experimental works, films by women, underrepresented communities, and non-Western masterpieces languish in the purgatory of partial validation. Plenty of Volume from devoted champions, perhaps, but cursed with limited Visibility and glacial Velocity.

Take the way we construct canons through what film scholar Donato Totaro calls "omnipotence level" - that magical combination of TV airings, repertory screenings, classroom syllabi, and streaming availability that keeps certain films perpetually in circulation. In 1952, when De Sica's Bicycle Thieves claimed the crown four years after its release, the relative scarcity of available films made such quick canonization possible. Today, we're drowning in ‘content’ while still somehow managing to preserve and circulate the same narrow slice of cinema.

The recent expansion of voting pools reveals less about changing aesthetic standards than about how previous generations weaponized the Three V's to maintain their grip on greatness. Every crack in the canonical fortress exposes the architecture of exclusion that built it.

Speaking Latin about films makes them important

The English language reserves its most grandiose etymological weapons for moments of cultural consecration. Our beloved suffix "-est" evolved from the Proto-Germanic *-ista, meant to mark absolute supremacy, a linguistic crown we still place atop words with the solemn ceremony of medieval coronations. Greatest. Finest. Best.

Each superlative performs a tiny coup d'état, where opinion seizes the throne of fact through sheer grammatical muscle. The result? A vocabulary of supremacy so intoxicating it could convince a room full of cinephiles that Mozart would struggle to get a meeting with Madonna's ex-agent.

Our current cinematic vocabulary emerged from Victorian nightmares about artistic hierarchy - all those dusty terms like "masterpiece" and "classic" that imagine film history as some grand atelier where master craftsmen hammer out pristine objects of unassailable quality. We cling to this fantasy where genius comes pre-certified, where cultural value arrives fully formed like Athena springing from Zeus's forehead (though in this case, probably wearing a Cahiers du Cinéma t-shirt).

Roger Ebert understood this racket perfectly. His assertion that great films "make us better people" belongs in the same rhetorical family tree as those Renaissance nobles who insisted their taste in art proved their divine right to rule. Darling, pass the popcorn and the papal decree.

The linguistics of legitimacy operate with tasty irony in film criticism. We built a fortress of fancy words around an art form made of light and shadow, projected illusions that disappear the moment someone flips the wrong switch. Our desperate grab for permanent markers of quality - "timeless," "universal," "transcendent" - betrays our anxiety about cinema's ephemeral nature. As if calling something "important" enough times will somehow protect it from changing dying formats. (Pour one out for your local Blockbuster.)

This verbal arms race has turned film discourse into a kind of linguistic Super Bowl, where every adjective must arrive pre-inflated with historical significance.

But here's where the vocabulary of supremacy pulls its finest trick: it transforms the speaker into a kind of cultural wizard, capable of turning subjective experience into objective truth through the magic of fancy words. The same linguistic sleight-of-hand that elevates a film to "masterpiece" status elevates its pronouncer to master status.

Suddenly you're speaking ex cathedra about aspect ratios at dinner parties, explaining Tarkovsky's use of time to your therapist, building little linguistic fortresses around your taste that absolutely nobody asked for. The more baroque the critical vocabulary, the more impregnable the cultural position. It's genius really. We created a system where the ability to deploy terms like "mise-en-scène" in casual conversation somehow proves you understand art better than people who simply feel things about movies.

If we count enough opinions they turn into facts

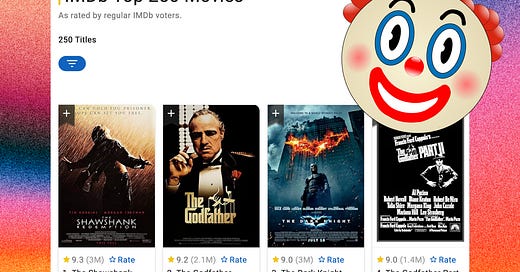

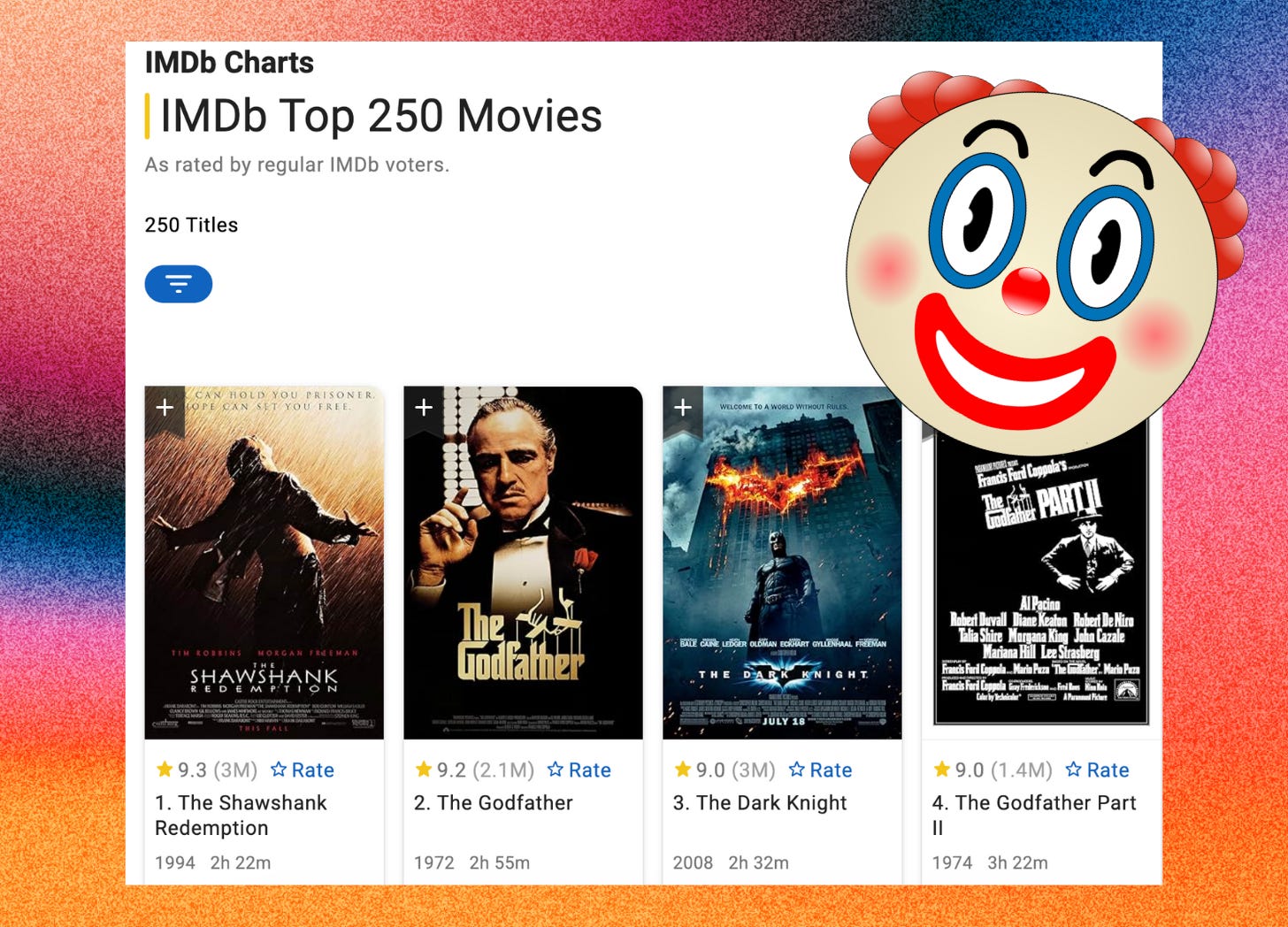

Our collective obsession with ranking art has spawned its own digital hellscape: the IMDb Top 250, where The Shawshank Redemption has reigned supreme for so long you'd think Andy Dufresne tunneled his way straight into the algorithm (love the film btw!). This list - a beautiful disaster of demographic skew and brigade voting - perfectly captures our desperation to turn subjective experience into mathematical certainty.

Nearly three million users have rated The Dark Knight, presumably believing their individual 1-to-10 scores will somehow average out into empirical proof of Christopher Nolan's genius. (The numerical distinction between "best film ever" and "pretty good time at the movies" apparently comes down to decimal points.)

The psychology behind this measurement mania would make Freud reach for something stronger than cocaine. We've built entire cultural ecosystems around the fantasy that art can be measured as precisely as mortgage rates. Letterboxd users craft elaborate personal rating systems with half-stars and quarter-stars, as if the difference between 3.5 and 4 stars might finally capture the ineffable quality of Bong Joon-ho’s directing. Rotten Tomatoes reduces critical discourse to binary thumbs while Metacritic pretends it can average opinion pieces into percentages. The underlying assumption would make a statistician weep.

If we just collect enough numerical data points, subjective experience will magically transform into objective fact.

This quantification compulsion reveals our deepest cultural anxieties. Every "Top 100 Films of All Time" list, every aggregated score, every ranked database operates as a kind of security theater for taste - pretending we can solve the messy problem of artistic value by throwing enough numbers at it. The more uncertain we feel about our judgments, the more desperately we cling to the fiction of mathematical precision.

We've created a parallel universe where Forrest Gump outranks 1927’s Sunrise on IMDb, Marvel films consistently score higher than Mizoguchi, and millions of users genuinely believe they can capture the transcendent power of cinema by clicking a star rating. (Though I guess five stars for Taxi Driver does take less time than writing a dissertation.)

You can't blame platforms for feeding this delusion. They're just meeting our insatiable demand for cultural certainty. But something profound gets lost when we pretend art operates like baseball statistics or stock prices. Every attempt to quantify greatness erases the beautiful chaos of individual response, the way a film hits differently at 15 versus 50, the impossible-to-measure magic of watching Jeanne Dielman in an empty theater on a Monday evening versus streaming it on your phone during a commute.

The numbers promise clarity while delivering nothing but the illusion of consensus. (Though I must admit, there's something poetic about millions of humans collectively trying to rate their own emotional experiences on a scale of 1 to 10. We contain multitudes, and apparently those multitudes really love The Godfather.)

A final note for people with taste 🫦

While the internet's prioritizing hot takes and SEO-optimized nothingness, I’m here trying to build a sanctuary for people who believe film and television criticism can be thoughtful, accessible and fun all at once.

For the price of a truly mediocre sandwich, consider joining the resistance with a paid subscription – it keeps independent film writing alive and the algorithms at bay.

Plus, you'll get exclusive access to After Credits, my monthly handpicked selection of films & tv shows that will make your brain do the happy chemicals AND save you from doom-scrolling.

Now go forth and raise those standards, darling.

- Sophie x

You’re the best film critic I read.

It's all egotism, isn't it?

Being mad that there's a ranking of great movies with which you disagree implies that in the end there is only ONE, CANONICAL "Greatest" list. Which means that you CAN know all the greatest movies, that ALL KNOWLEDGE is within your terrestrial grasp.

Which... C'mon fam. That's ridiculous.

We need to stop placing weight on "the greatest" and humbly concede that there is an ever-morphing canon from which we can always shape and change and more importantly challenge. Which involves dropping the ego and trying new things, usually from people not like us. I wish people like Paul Schrader realized this.

Fromtheyardtothearthouse.substack.com