My 2013 Tumblr archive used to read like a particularly earnest teenager's attempt to process American pop-punk through German Expressionism. Between frantically reblogging Panic! at the Disco lyrics overlaid on Victorian mourning portraits and spending hours perfecting the contrast on my badly-lit concert photos, I somehow convinced myself I was creating high art. The entire platform operated on this delightful contradiction - we were simultaneously deadly serious about our aesthetic choices and completely aware of how ridiculous we must look to anyone outside our bubble.

The thing about that era of the internet is that we didn't know yet how to perform ourselves into submission. Our physical circles were tiny, suffocating things until Tumblr taught us how to pick the locks. Before Twitter turned us all into personal brands. Before Instagram made us calculate the exact angle of our morning light. We were still learning how to be weird in ways that made sense only to ourselves and the strangers who somehow found us in that strange corner of the worldwide web.

Oh I miss that internet. Not the current version where Mark Zuckerberg keeps insisting Threads is where culture happens, but that gorgeous “wasteland“ where Tumblr fandoms were building elaborate monuments to absolutely everything and nothing. Back then, you could log on at 3am and find a 47,000-note post that started as someone's sleep-deprived observation about Gothic literature and evolved, reblog by reblog, into an accidental masterpiece of queer theory. The platform worked like a particle accelerator for somewhat odd people, like myself, smashing together references until something new and strange emerged from the collision. obsession_inc called this phenomenon ‘transformational fandom’ in their 2009 essay. More on this later.

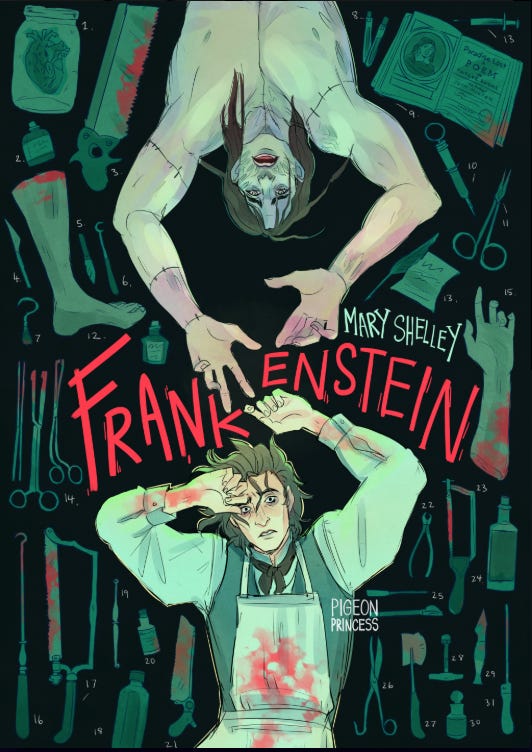

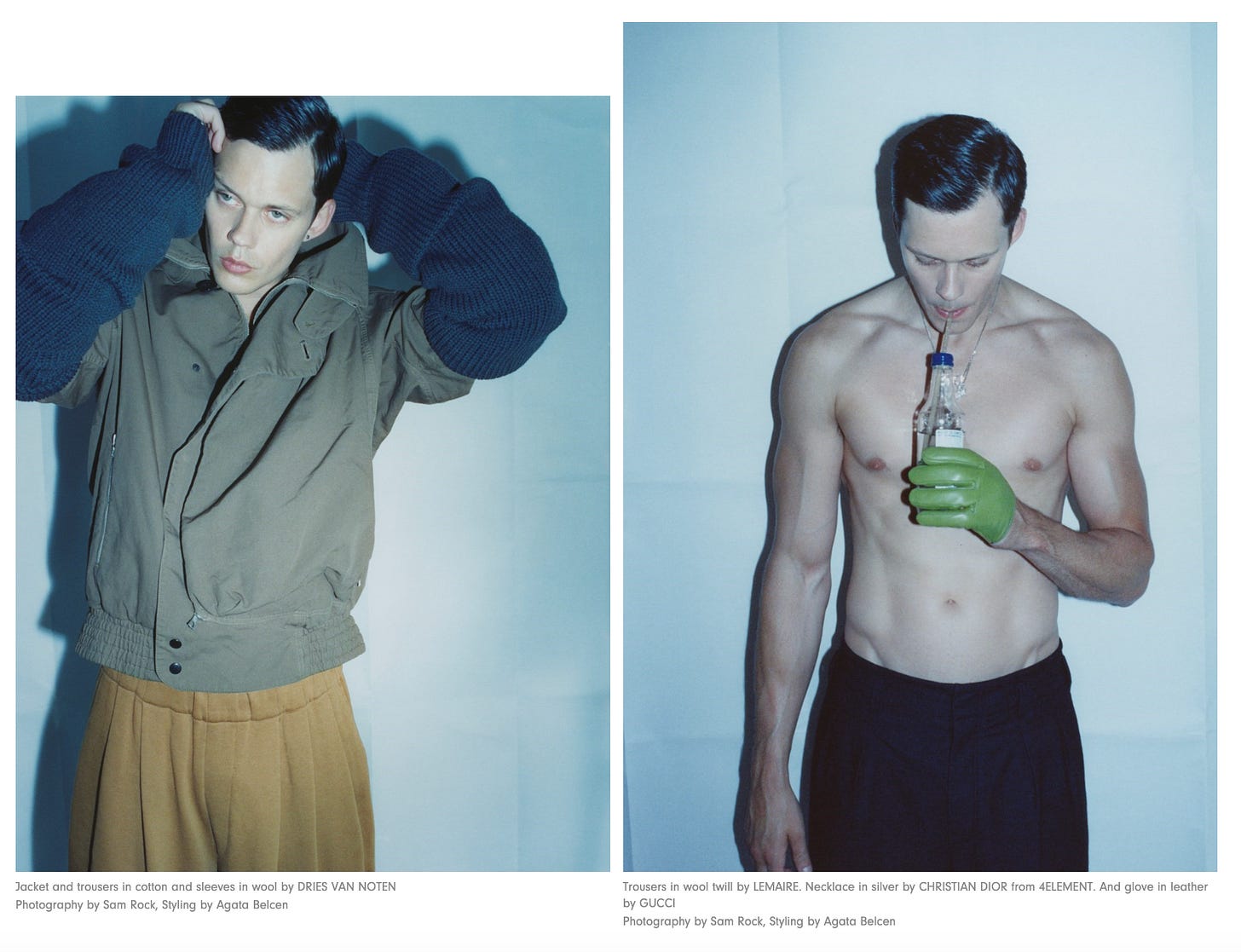

That's the internet that produced Hemlock Grove fan fiction, a show that could only exist in that precise moment when streaming executives were desperate enough to greenlight anything and Tumblr's sticky brain rot had taken over underground online culture. Netflix handed over millions to let werewolf transformations look like Caravaggio paintings reimagined by kids who spent too much time on fashion blogs. The series itself was gloriously incoherent - the kind of sensational disaster that launched a thousand gifsets captioned with lyrics from The National. But it established Bill Skarsgård as someone we’d only come to know in the following years: an actor who, just like Tumblr kids, understood that performance is often not about authenticity nor relatability - but about spectacular artifice.

“The performance becomes most compelling when it resists naturalism. Artifice creates distance, but paradoxically allows us to see deeper truths.”

—Alex Clayton, Writing about Performance

In the decade since, through Pennywise's otherworldly laugh (developed while driving through Los Angeles in DIY clown makeup) to Castle Rock's deliberately ambiguous Kid to his latest transformation into Nosferatu's Count Orlok, Skarsgård has carved out territory that Tumblr culture instinctively nurtured: True monstrosity requires distance from relatability. This is a concept that major studios are becoming increasingly allergic to, of course, frantically bringing every villain's rewritten origin story to life. Maleficent was misunderstood, Cruella just needed better PR, the Evil Queen probably had body dysmorphia, Joker had a mental health problem, Wicked was bullied, Ursula was fighting marine gentrification, the list goes on.

In The Bloody Chamber, Angela Carter crafted feminist Gothic reimaginings where the monster's magnetism stems from its potential for destruction. Her protagonist doesn't dream of saving the Erl-King. She fantasizes about strangling him with her own hair after he ruins her.

“Erl-King will do you grievous harm. But he laughs at me as I lie at his feet...I shall strangle him with them, the ribbons of my hair, and then bind myself around his neck.”

—Angela Carter, The Bloody Chamber

The horror genre has always thrived on this paradox - we're drawn to what might destroy us. Studios keep trying to sand down those edges, convinced audiences need psychological scaffolding to embrace darkness. But Carter's work reminds us why that instinct misses the point entirely. After all, it's what makes Skarsgård's performances so compelling. His monsters don't apologize. They don't explain. They don't arrive with trigger warnings or character development arcs. They don't want your understanding. They want your on-your-knees discomfort.

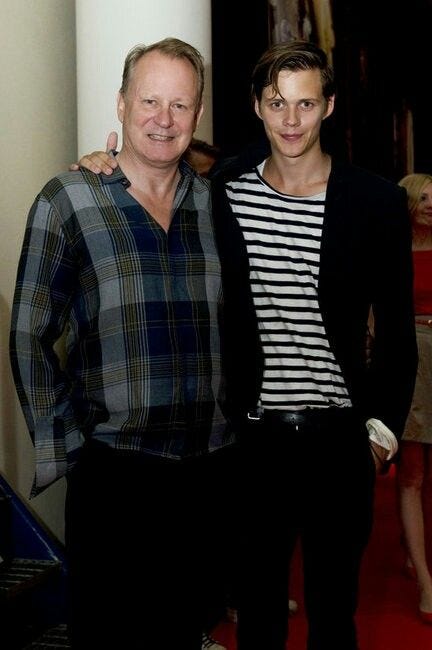

Bill’s dad is a magnificent vampire factory

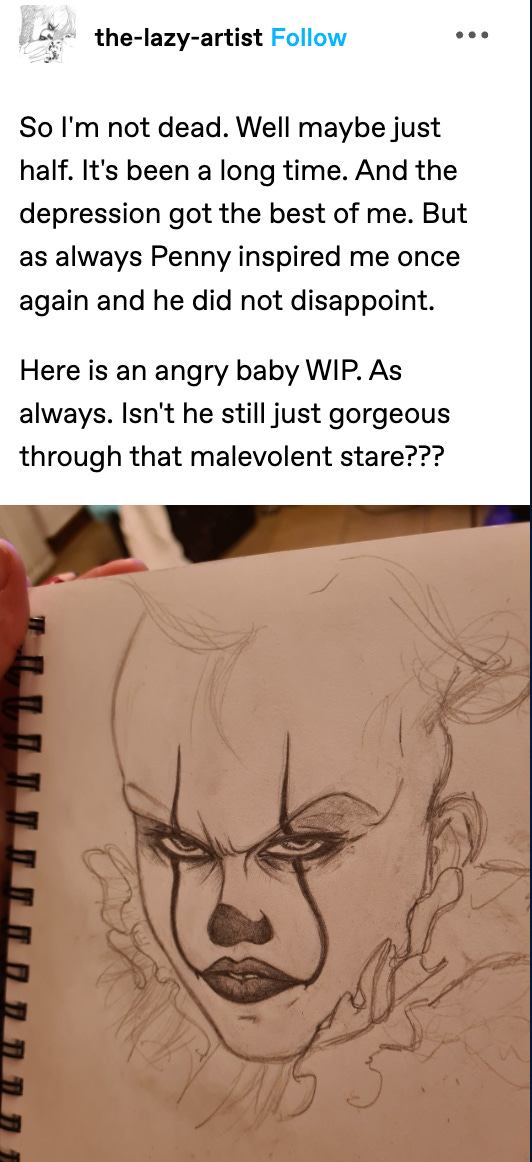

Bill is the son of Stellan, brother of Alexander and Gustaf, blessed with the same angular beauty that launched a thousand Swedish vampire fantasies - and all he wants to do is spend three months learning Japanese corpse dancing and working with opera singers to push his voice into registers that made his own brother recoil in horror. "What the fuck is going on?" Gustaf asked after hearing the playback, echoing the exact mix of repulsion and fascination that once made Tumblr such a fascinating space for exploring darker impulses. Crystal sharp gifset worthy, if you ask me.

Bill Skarsgård's early film education looks like something dreamed up by a European arthouse director. Growing up in a Stockholm apartment building where the Skarsgårds occupied two floors - cousins above, grandparents across the street, and every night someone's projector flickering to life. While other Swedish families maintained polite distance, the Skarsgårds created their own gravitational field.

Young Bill would sprawl on the couch next to Stellan, fresh off shooting Lars von Trier's latest descent into madness (as you do with your family on a Tuesday night) or wrapping Good Will Hunting, watching his father build a cinematic curriculum. Sergio Leone westerns dominated weekends. Kurosawa commanded weeknights. Charlie Chaplin's silent comedy offered Sunday relief. But what separated these screenings from standard father-son bonding was Stellan's fierce moral framework. Violence could never be romanticized. Power Rangers? Strictly forbidden. Too many consequence-free head kicks.

Yet this restriction sparked something unexpected in Bill. "I've never held those ideals," he says now of his father's stance. "I grew up in a different time. I don't think playing a violent video game makes you a violent person. I've always found violence fascinating." The son of Swedish cinema's moral compass developed an obsession with exactly what his father tried to shield him from - not violence itself, but its aesthetic potential.

As the fourth of six children, Bill found himself quite literally pushed out of his mother's orbit. "You kind of pick what side of the bed of your parents you sleep on," he explains with characteristic deadpan. "My sister's a year and a half younger than me, so I got pushed off from Mom's side fairly early onto Dad's." While his mother devoted herself to helping recovering addicts after working through her own struggles, Bill gravitated toward his father's more constructed relationship with feeling. Sitting on his father's side of the bed shaped more than just Bill's movie education - it gave him front row seats to the psychological thriller playing out in his own development as an artist. The way he gravitated toward his father's constructed relationship with feeling mirrors what Freud discovered when he started poking around in our collective psyche back in 1919.

“The uncanny is that class of frightening things which leads us back to what is known and familiar. It is the return of the repressed.”

— Sigmund Freud, The Uncanny

Writing about "the uncanny," Freud mapped out territory Gothic writers had been mining for centuries: our deepest fears don't come from the alien or unknown, but from the familiar twisted into new shapes. A child's beloved doll becomes terrifying when its painted smile shifts a millimeter too wide. A family home breeds horror the moment something moves in the shadows where nothing should move. The uncanny hits hardest when it forces us to confront what we've tried to bury - those impulses and desires proper society demands we suppress.

Bill is too strange for Swedish cinema

Swedish cinema loves a certain kind of brooding. They'll fund endless movies about quiet men staring at lakes. They'll greenlight another meditation on seasonal depression. They'll take Alexander's stoic romance or Gustaf's calculated intensity or even Papa Stellan's capacity for controlled menace. But Bill's particular strain of weird? That was too much even for the country that gave us Ingmar Bergman's whole thing about Death playing chess (writer’s note: I love Swedish cinema, btw).

After a small role in Linklater's Fast Food Nation prompted him to abandon his film theory classes at UT Austin, Skarsgård returned home to find his intensity overwhelming Sweden's careful relationship with success. "Sweden is very known for tall-poppy syndrome," he explains. "You can be successful but not too successful." The country produces more brilliant actors than IKEA produces allegedly easy-to-assemble furniture, but its exile of him was madly ironic; Pushing him to drop film theory only to chase the kind of roles that would later make their film theorists lose their minds.

His performances in films like Behind Blue Skies proved so uncompromising that they made Swedish film executives nervous. Not because the performances failed - but because they refused to make themselves palatable. While his contemporaries were crafting diligent careers in Stockholm, appearing in the right festivals and saying the right things about Nordic noir, Bill was developing the kind of aesthetic that would eventually lead him to spend three months perfecting a vampire's vocal fry. Sweden had no idea what to do with an actor more interested in Japanese corpse dancing than appearing in another movie about divorce in December.

Robert Eggers confirms this, slyly proclaiming that Skarsgard out-occults even his own level of weird. “I remember early on, him trying to talk to me about what it meant to be a dead sorcerer—and I’m into some pretty heavy occult shit, but he was on a different level,” Eggers said with a laugh. “I was like, ‘This sounds accurate, but I don’t know how to converse about this with any fluidity.’ ”

Tumblr and Skarsgård both got kicked out of the cool kids' table for the same crime: reimagining their thirst for monsters. While other platforms rushed to verify celebrity accounts and amplify elitist, conventional, voices, Tumblr's reblog function created something more radical, a space where meaning accumulated through preservation and reinterpretation rather than explanation. As Ángel Mateos-Aparicio argues in Making Sense of Popular Culture:

“Monsters in postmodernity are never static; they slip between categories, blurring the boundaries of desire and terror. They challenge the moral binaries of good and evil, allowing audiences to project their own ambivalences onto these figures.”

— Ángel Mateos-Aparicio, Popularizing Postmodern Utopian Thinking in Science Fiction Film

Postmodern narratives, both present in Tumblr culture and Skarsgård’s career choices, dismantle traditional tropes. They challenge the notion that any single interpretation can claim dominance. They reinterpret vampires and werewolves and clowns as simultaneously seductive and horrifying.

And that's exactly what made both so threatening to their respective gatekeepers. A text post could travel through hundreds of blogs, gathering new layers of meaning with each reblog, its original author's identity becoming increasingly irrelevant to its impact. The platform's "heritage posts" emerged not through individual genius but through collective curation, each reblog adding another brushstroke to the artificial beauty being constructed. It's the same approach Skarsgård brings to his monsters: not method acting immersion but careful, deliberate artifice built piece by piece. Both refuse to let their work be pinned down to a single authoritative meaning. Like the best postmodern art, they gain power precisely by slipping free of explanation.

Bill is very good at economics

Nothing ruins a grocery store run quite like fame. Little Bill Skarsgård would get sent down the aisle for milk only to hear strangers stage-whispering about his dad. Must be weird, having your family Frosted Flakes mission turn into an impromptu Nordic celebrity spotting. That early taste of fame's weirdness shaped how Skarsgård would later navigate Hollywood.

His first real swing at Hollywood was a $35,000 role in Hidden Figures. That's right - $35,000 for an entire year. In Los Angeles. Where a parking spot costs more than rent in Stockholm. Most actors would have padded that with network TV guest spots, building the kind of IMDB page that leads to CW teen dramas and eventual Marvel consideration but Bill wasn’t just broke. He was strategically broke. Sleeping on couches broke. The kind of broke that happens when you decide to become unavailable right when Hollywood wants you most available.

"I used my old UT economics class," he says about this period. "Just supply and demand. Took supply out of it and hoped demand would follow." This is the kind of strategy that should get your management team fired: Making yourself harder to find when Hollywood finally knows your name. But Skarsgård bet on the idea that would later turn him into a household name - being undefinable is more interesting than being everywhere.

Tumblr thirsted so Bill could bite

In 2013, after Yahoo acquired Tumblr for $1.1 billion, new CEO Marissa Mayer promised users that nothing would change - that classic Silicon Valley fairytale where acquisition somehow means preservation. The reality hit harder. Twitter and Facebook had already transformed into verification hunger games, turning blue checkmarks into digital nobility. Tumblr offered something radically different: a digital speakeasy where identity itself became fluid art. No verification badges meant no hierarchy. A viral post about Victorian sexuality could come from a Harvard professor or a teenager in Toledo. That shrine to beautiful sadness might have ten followers or ten thousand.

The platform's users called it "a perverse equality," and they meant it as the highest compliment. This anonymity created possibilities unthinkable on other platforms. Queer kids could explore their identity through SOPHIE avant garde bops and high-contrast fashion photos. By 2014, this freedom had evolved into what users called anti-FOMO culture, a complete rejection of Instagram's manufactured joy.

Your Tumblr could be equal parts coming out narrative and artfully composed photos of empty swimming pools at 3am. Nobody demanded you explain which parts were performance and which were confession. The platform became a sanctuary for aesthetic depression, for beautiful darkness, for the kind of emotional exploration that terrified advertisers. Verizon's acquisition of Yahoo in 2017 proved exactly why. Their immediate sanitization campaign didn't just alienate users - it crushed the precise mechanism that made Tumblr valuable. Its refusal to explain itself to algorithms.

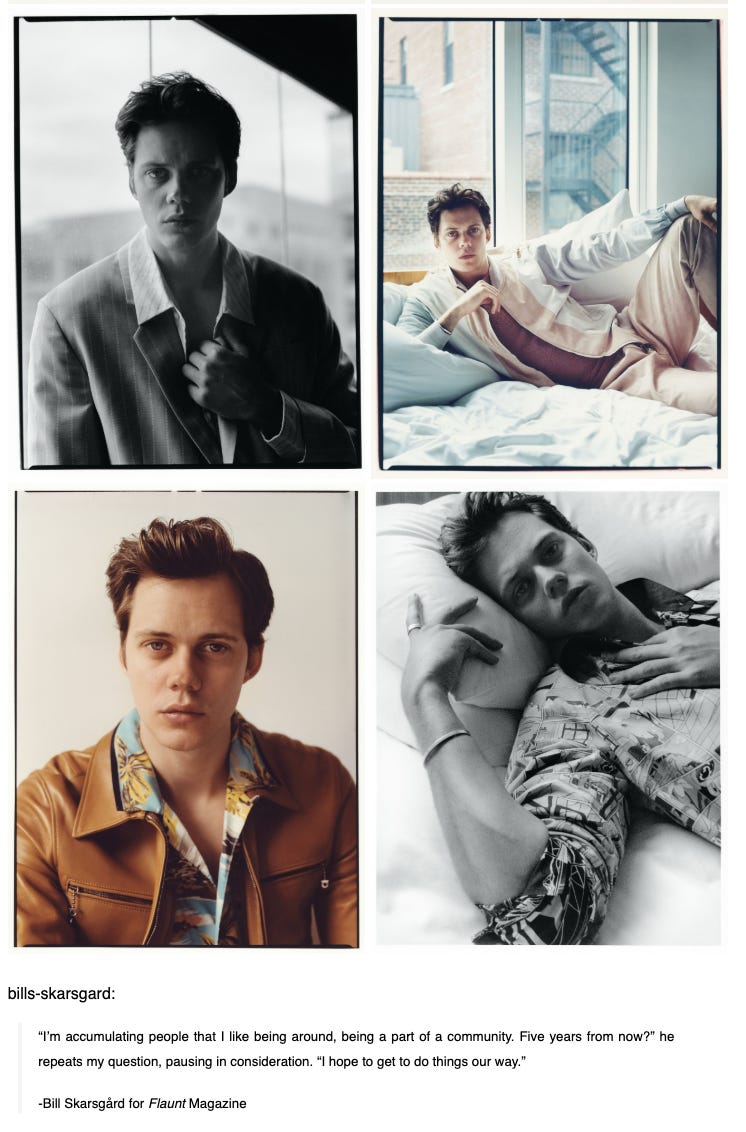

Skarsgård's career reads like a one-man resistance to this same corporate sanitization. While other actors his age maintain PR-approved content schedules, he remains gloriously absent from social platforms. He shows up to premieres like someone who runs a Tumblr dedicated to abandoned Soviet factories - fascinating and chaotic precisely because he refuses to explain the aesthetic. "I'm accumulating people that I like being around," he says of his long-term strategy, describing a vision where those same people can adapt books they admire into films they want to make. "Five years from now? I hope to get to do things our way."

This perspective makes particular sense for someone who watched fame devour his family's privacy in real time. Swedish tabloids treated the Skarsgård surname like an all-you-can-eat buffet by the time Bill was booking his first roles, two-thirds of all articles about him started with some version of "Here we go again...". Rather than fight these comparisons, he learned to use them - studying his father's performances not to emulate them but to understand how artificial distance could create something more compelling than manufactured intimacy. When every rising star gets packaged into algorithm-friendly content, Skarsgård keeps proving that audiences crave exactly what Tumblr's corporate owners failed to understand. Beauty works best when it maintains its mysteries.

Bill knows what it takes to run a Tumblr blog

A year before Bill Skarsgård disappeared into Count Orlok's shadows, he was fighting a different kind of darkness as Eric Draven in The Crow. His take on the resurrected avenger emerged from the same creative philosophy that got him exiled from Swedish cinema - a bone-deep commitment to keeping characters magnificently unknowable. Studio executives wanted another Brandon Lee, all righteous vengeance and tragic romance. Instead, Skarsgård delivered something closer to a German Expressionist nightmare wrapped in black leather and face paint. The film stumbled at the box office (spoiler: it was not good), but the performance itself feels like a defiant bridge between his early work on Castle Rock and his current transformation in Nosferatu.

As The Kid on Castle Rock, Skarsgård crafted the kind of character that would have spawned a thousand aesthetically coordinated Tumblr shrines in 2014 - gifsets of meaningful glances, elaborate theories about his true nature cataloged in powder-blue Helvetica, endless reblogs debating whether that slight smile meant salvation or damnation. The show's creators originally pitched The Kid as a straightforward antagonist, another damaged antihero for prestige TV's endless parade of misunderstood men. But something in Skarsgård's performance kept pushing them toward stranger territory. Every episode added new layers of ambiguity until the writers themselves seemed unsure whether they'd created a victim or a monster.

Robert Eggers spent eight years searching for his Count Orlok, cycling through actors who could never quite capture the particular breed of beautiful horror he envisioned. When Skarsgård finally emerged as a contender, it wasn't because he fit the traditional vampire mold. His screen tests revealed something the director hadn't even known he was looking for - the kind of persistence to artificial beauty that once made Tumblr such a fascinating crucible for exploring darker impulses.

Robert Eggers: Well, I clearly wanted you to get the role or I wouldn’t have gone through all that hullabaloo. Because I had the realisation that, for Orlok to be a corpse, and for the romance to still work, it would be helpful for the audience to know that there is someone young and beautiful under there. And I thought, Bill’s so tall and so skinny, which is perfect for the physicality I was looking for, and he’s so good … And then I saw It Chapter Two. The scene where you’re Pennywise but as a guy …

Bill Skarsgård: Yeah, Bob Gray, the human.

I keep rewinding that Bob Gray scene until my laptop fan starts screaming. This is what Eggers saw - someone who understands the knife's edge between grace and corruption. The way ballet dancers snap their own bones into submission. The way martyrs painted their own wounds into roses. That moment when beauty decides to break itself.

Tumblr worshipped that level of effort. We didn’t appreciate the surface stuff all that much - the fake blood and flower crowns and pastel grunge bullshit. But we loved to experience that electric current that ran through everything we made. The way we'd spend hours perfecting each mutation, each transformation, until it sang with its own twisted harmony. We knew then what Bill knows now - the most devastating monsters are the ones who remember exactly what they gave up to become monstrous.

Now tell me this is not a Tumblr kid.

Bill wants you horny for Nosferatu-core

December 2018 marked the moment both Tumblr and mainstream entertainment faced the same crushing pressure to make themselves palatable. As Bill Skarsgård's demonic clown was still sending shockwaves through pop culture, Tumblr executives unleashed their own horror show: a "no adult content" policy that obliterated entire communities overnight (though this has since been reversed). At the time, fan fiction writers who'd spent years building intricate mythologies watched their stories vanish into the internet void. Artists posting classical nudes got lumped in with hardcore pornography. Underrepresented communities saw their perfectly innocent content flagged as inappropriate, their very existence deemed too dangerous for advertisers.

What the platform's corporate overlords never grasped was something film theorist David Bordwell had already pointed out:

“Violence, when abstracted into aesthetic form, retains its horror but acquires a strange allure. The audience is confronted not just with the act, but with its beauty—forcing a reckoning with their own emotional response.”

— David Bordwell, On the History of Film Style

Tumblr kids weren't just shoving gore into the void for kicks. I watched them turn Skarsgård's murder-clown into something you'd find in a McQueen lookbook, and nobody blinked. God, what a time. The platform used to wave its freak flag right in the terms of service - "show nuts, whatever" was their actual legal position. Then the suits rolled in with their content guidelines thicker than a Catholic school rulebook. It worked, technically. They got their advertiser-friendly wasteland. And all it cost them was everything - watching that $1.1 billion evaluation nosedive into WordPress pennies felt like watching someone set fire to the MoMA and calling it strategic downsizing. The market speaks in numbers but this felt personal, like getting a break-up text written in Excel formulas.

Six years later, I’m watching Skarsgård's Orlok claw its way out of Eggers' imagination and it feels like finding a time capsule buried in obsolete code. That specific frequency we used to chase through ask boxes, before venture capitalists decided to baby-proof the internet's most fascinating experiment. His performance pulses with the kind of voltage that makes studio executives reach for their pearls and their psychological profile templates. But I know this creature. I know the precise frequency where art stops explaining itself and starts eating you alive. The kind that makes you want to grab the nearest person by their shoulders and scream "don't you feel that?". But they won't feel it. They weren't there when we learned to transmute our shadows into light.

"He's gross, but it is very sexualized. It's playing with a sexual fetish about the power of the monster and what that appeal has to you. Hopefully you'll get a little bit attracted by it and disgusted by your attraction at the same time."

— Bill Skarsgård on Nosferatu’s Count Orlok 🙂↕️

These days I scroll past the latest villain origin story and taste copper in my mouth. The franchises want us docile, need us reaching for narratives that explain away the magnetic pull of what should repel us. But back in that digital underworld, we knew better. We wrapped ourselves in darkness without needing it notarized first. Now Skarsgård stalks through Hollywood's carefully plotted gardens like a match looking for kerosene, each performance a middle finger to the content moderators who thought they could edit the teeth out of our monsters. Hopefully, he carries the truth we carved into Tumblr's walls. It’s the fiercest art that leaves you bloody and breathless, wondering why you're still begging for more.

P.S. Apparently hitting that little heart button is the equivalent of leaving a good tip for the algorithm™ gods. So if you enjoyed reading this, please give it a like.

A final note for people with taste 🫦

While the internet's prioritizing hot takes and SEO-optimized nothingness, I’m trying to building something genuine with this newsletter: a sanctuary for people who believe film and television criticism can be thoughtful, accessible and fun all at once.

For the price of a truly mediocre sandwich, consider joining the resistance with a paid subscription – it keeps independent film writing alive and the algorithms at bay.

Plus, you'll get exclusive access to After Credits, my monthly handpicked selection of films & tv shows that will make your brain do the happy chemicals AND save you from doom-scrolling.

Now go forth and raise those standards, darling.

- Sophie x

What an absolutely gorgeous piece. I have never understood why today's film execs insist on sanitizing villains. I don't want to know their tragic backstory and I don't want them to be "humanized." Doing so completely removes that gut feeling that makes them so compelling. It's almost like l'appel du vide... you know it's horrifying. You know it's wrong, but still there is temptation. Bill has always done an incredible job of portraying that in his work, and I admire him for it. Thank you for your article! It was a delightful and wildly entertaining read!

This is fucking brilliant. I'm not sure I agree with a word of it, but I'm too dazzled to care.