the comfort of blaming everything on butterflies

The strange death of 'global network films' marked the beginning of something worse.

The first time I watched Michael Haneke's Code Unknown (just last week), my mind kept drifting to Fredrick Jameson's post-modernist idea that we're all attempting to map our place in systems too vast to comprehend. Haneke's film, composed of roughly fifty scenes shot in unbroken long takes, seemed determined to expose the futility of such mapping.

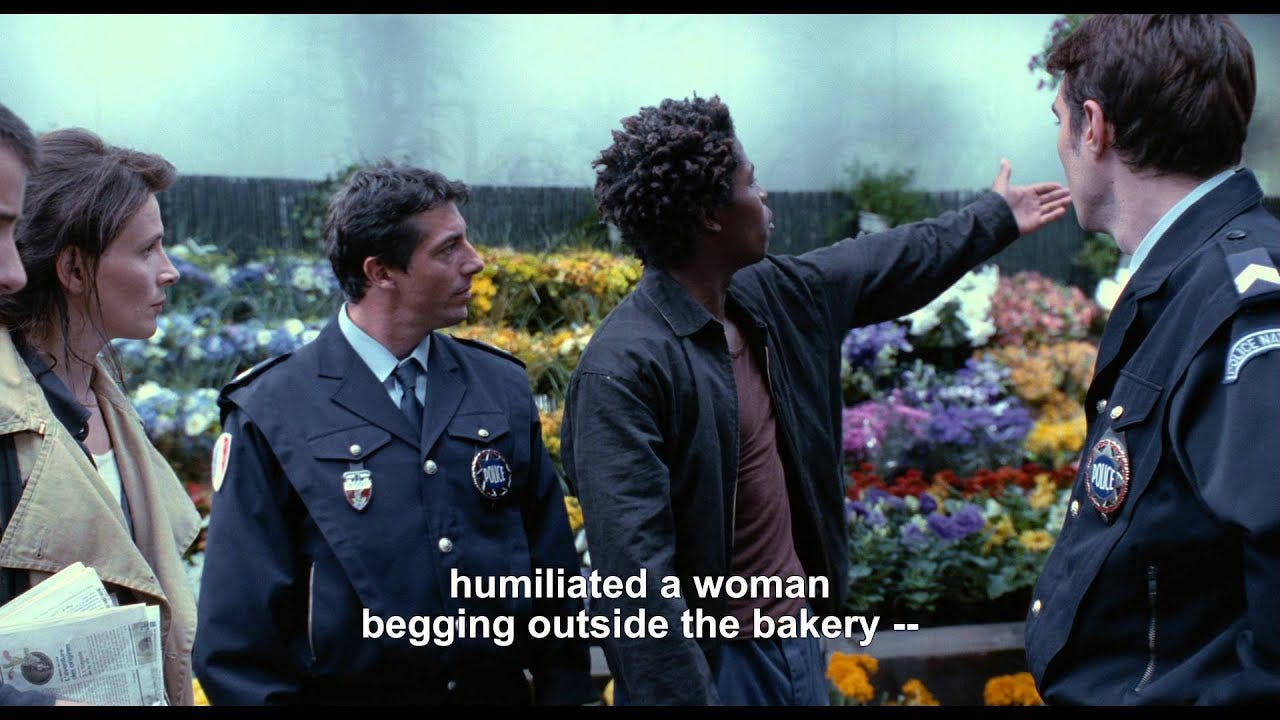

The film opens with a deaf student failing to convey an emotion through sign language, and this image of thwarted communication ripples through everything that follows. An African immigrant witnesses this casual cruelty and confronts him. A local shop owner misinterprets the escalating tension. The police arrive with their own prejudices. Each person in this sequence sees a completely different reality playing out, and Haneke captures it all in one masterful shot that somehow never calls attention to its own virtuosity.

I came to Code Unknown through Brock Eldon, one of this newsletter’s founding members (who, like all founding members, get to request one film/tv essay from me each year). When he suggested the film, I thought it might illuminate something about cinema's relationship with connection. What I found instead was a film that seemed to take perverse pleasure in denying every satisfying intersection that mainstream movies had trained me to expect – a fitting choice for a newsletter obsessed with endings, given how stubbornly this film refuses to provide one.

The contrast hit hardest in the film's Metro sequence, where actress Anne (Juliette Binoche) endures escalating harassment from a teenager while other passengers perform that studied ritual of urban unseeing. The moment captures volumes about city life without straining for significance - no swelling music to telegraph emotion, no convenient revelation about shared humanity. Even when an elderly man finally intervenes, first carefully removing his glasses in anticipation of violence, the scene refuses the easy catharsis that a Hollywood version would demand.

The film moves this way throughout, through fragments where attempted connection leads to deeper isolation, where meaning constantly slips through our fingers like sand. A Romanian woman begs on the street until police demand her papers, leading to deportation. We next see her back home, but the journey between those moments stays deliberately opaque. Anne acts in a film-within-the-film called "The Collector," but we only glimpse fragments of this performance, each one deepening our sense of lives that exceed any single frame or story.

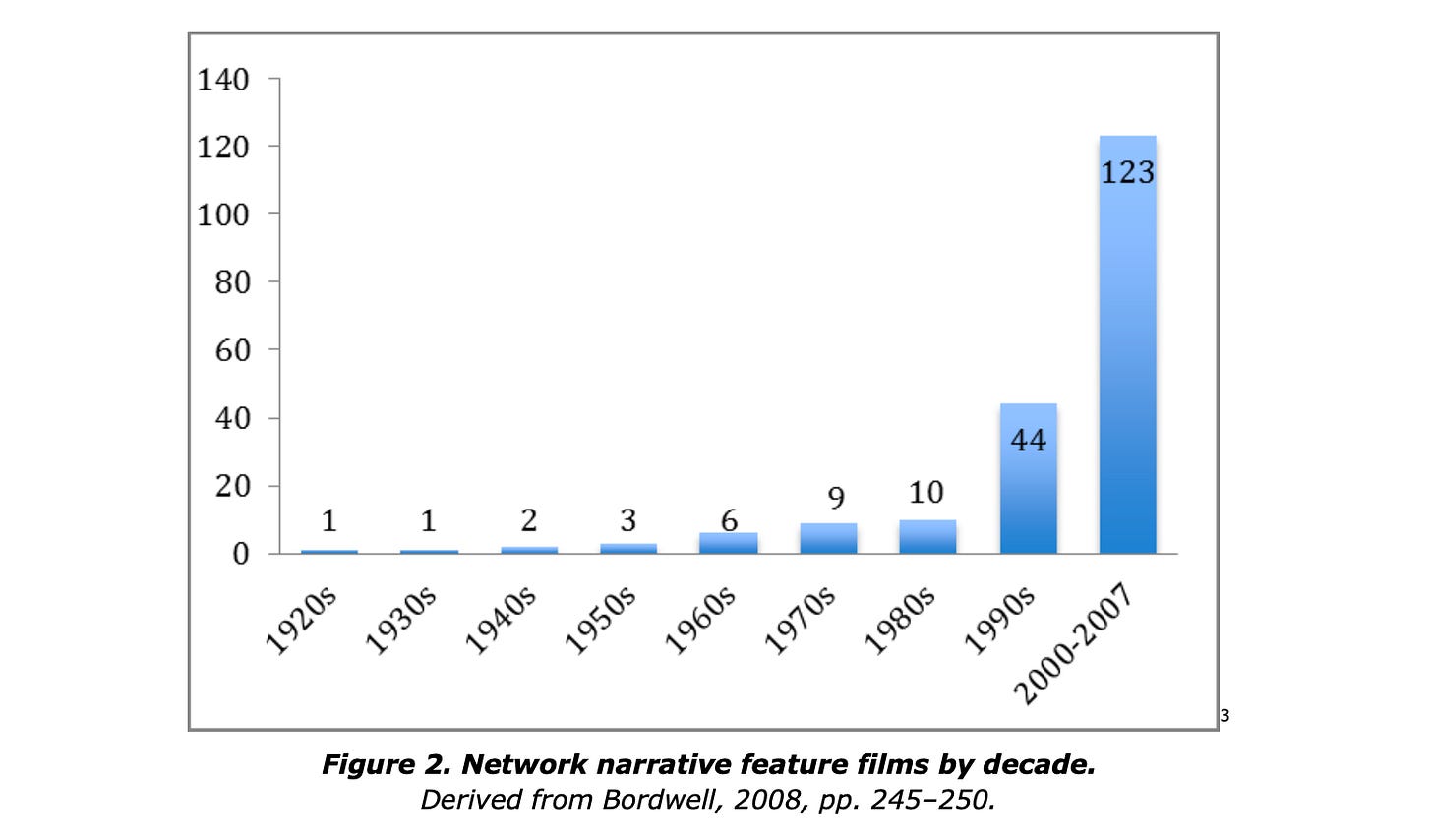

The realization started creeping in around the third abrupt cut to black - those moments where Haneke ends scenes a beat or two before conventional resolution. While other “network narrative” feature films of the early 2000s were engineering elaborate coincidences to suggest that everything was secretly connected, Code Unknown kept insisting on the spaces between, the stories we don't get to see, the connections that fail to materialize. This wasn't just artistic perversity. Through its very structure, the film illuminated something crucial about how Hollywood had been processing our collective anxiety about globalization.

All those carefully constructed intersections in films like Babel and Crash suddenly felt like elaborate defense mechanisms - ways of making vast systemic issues feel manageable by reducing them to personal epiphanies and cosmic coincidence. Code Unknown stripped away those comforting pretenses. Its fragments remained stubbornly fragmented, its characters proximate but perpetually out of sync, its narratives deliberately incomplete. The effect was oddly liberating, like finally admitting a truth we'd been working very hard to avoid.

Which made me wonder: what exactly were all those other network narratives trying so desperately to resolve?

That time BMWs solved globalization

In the early 2000s, Hollywood discovered a peculiar magic trick: if you crashed enough cars into each other, eventually they'd reveal the hidden connections binding humanity together. The trick worked best with high-end vehicles - a Mercedes in Mexico City colliding with a BMW in Morocco, the impact rippling through time zones until some vital truth about globalization emerged from the wreckage. Directors like Alejandro González Iñárritu and Paul Haggis perfected this cinematic calculus, engineering elaborate pile-ups that turned random accidents into cosmic significance.

Their films promised a seductive equation: enough carefully choreographed coincidence plus sufficient cross-cultural collision equals enlightenment. The math wasn't exactly subtle - Crash literalized it right in the title - but audiences devoured these intricately constructed networks of meaning. We wanted so badly to believe that somewhere in all our messy global entanglements, a hidden pattern waited to be discovered.

The formula proliferated through the decade like a viral trend, spawning ambitious experiments in global storytelling even as it exposed Hollywood's limits. Iñárritu's 21 Grams used a fatal car accident to weave together a mathematician, a grieving widow, and a born-again ex-con, their lives intersecting with the precise choreography of an existential ballet - a formal innovation that made visible what traditional linear narratives couldn't touch. Hotel Rwanda transformed the 1994 genocide into a node connecting Rwandan, Belgian, American, Canadian and UN bureaucracies, while Beyond Borders stretched its network across African refugee camps and conflict zones in Southeast Asia and Eastern Europe, each film straining against commercial cinema's boundaries to map previously unfilmable systems. Lord of War tracked arms dealing through a web spanning from Brooklyn basements to African warlords, each transaction another strand in capitalism's favorite spider web.

The genre kept expanding its reach, more fascinating in its noble failures than its occasional successes - these films crashed against the limits of narrative like waves against a seawall, revealing the shape of what they couldn't quite capture. By mid-decade, every global crisis arrived pre-packaged with its own set of intersecting storylines and manufactured moments of cross-cultural enlightenment, the industry's ambitious impulse to map the unmappable calcifying into formula. You couldn't throw a rock at the multiplex without hitting some character about to discover their secret connection to the military-industrial complex, but those connections revealed as much through their artificiality as their insights.

This desire for connection emerged alongside academic theories about "the butterfly effect" and "six degrees of separation," reflecting a growing awareness of hidden patterns in complex systems. But the films themselves operated on three distinct levels of networks - their fractured narrative structures, their themes of global interconnection, and their very production models. Amores Perros marked the first time private investment exceeded public support in Mexican cinema, while Babel, also by Alejandro González Iñárritu, required five different production companies spanning multiple continents just to exist. These films weren't just about global networks - they were products of the very systems they attempted to map.

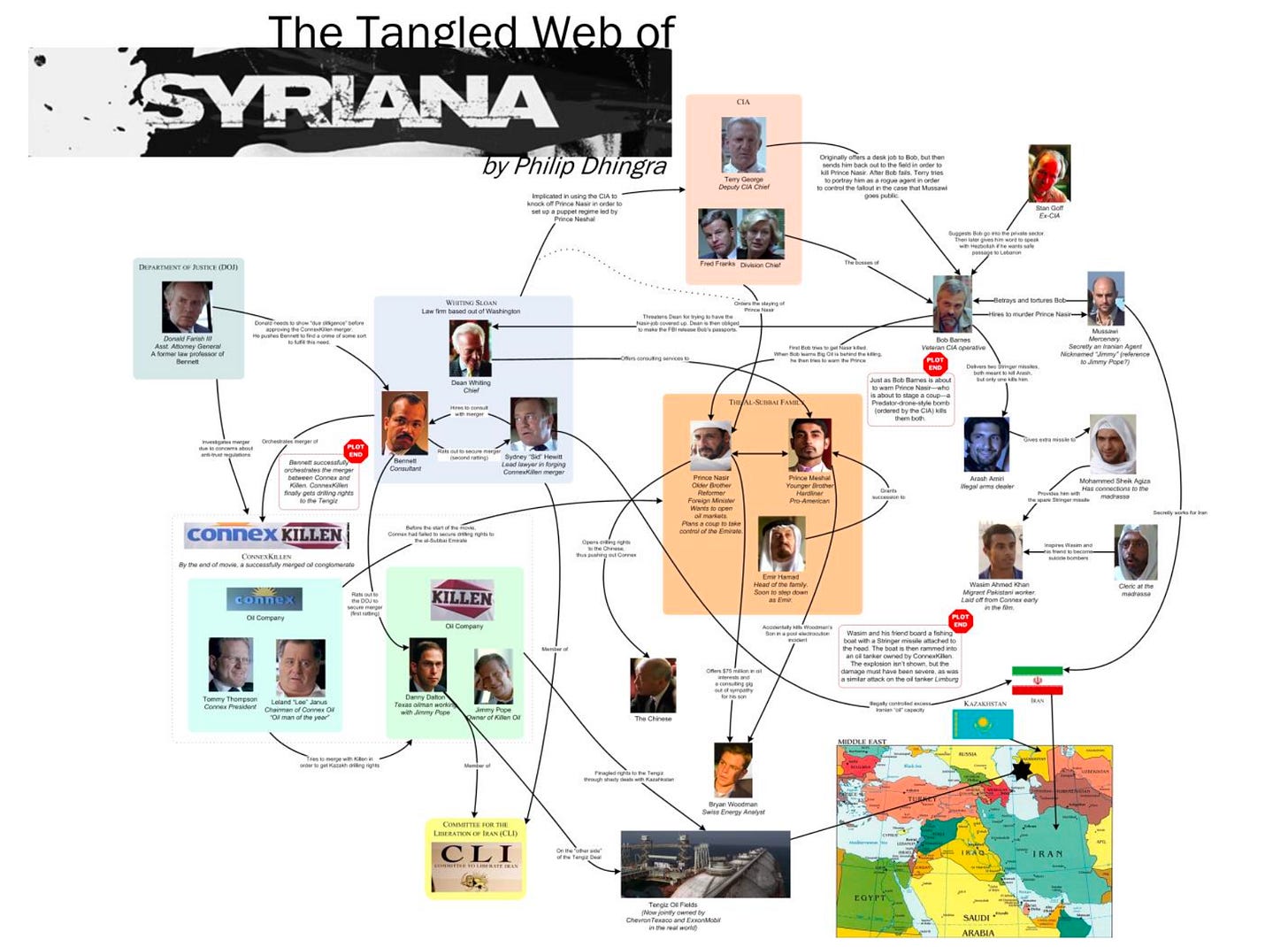

When Traffic tried to untangle the complexities of the international drug trade through interconnected storylines, it relied on what scholars termed "magical neoliberalism" - using coincidence and chance to make visible systems that seemed to defy representation. The films became increasingly ambitious in scope: Syriana spanned four continents and 220 locations in its attempt to map oil politics, while Babel wove together stories from Morocco, Japan, Mexico and the United States through the trajectory of a single bullet.

The secret ingredient in this global gumbo was what film theorists called "risk and randomness to map a fantastic network of interrelations." Characters needed to literally crash into each other because genuine connection felt increasingly impossible - every collision promised the possibility of revelation. A Mexican nanny takes her wealthy employers' children across the border: epiphany about immigration. A police officer pulls over a Black film director and his wife: epiphany about racism. A corrupt oil executive confronts the human cost of corporate politics: epiphany about capitalism.

The formula grew so reliable it practically became its own genre, with each new entry promising bigger connections and more impressive star-studded collisions. Brad Pitt discovering shared humanity in Morocco. Sandra Bullock learning tolerance in Los Angeles. Matt Damon unraveling conspiracy in the Persian Gulf. The coincidences grew more elaborate as the systems they attempted to represent became increasingly complex.

Yet even at their peak, these films contained the seeds of their own undoing. The more ambitious they became in scope, the more their attempts at connection began to feel artificial. Traffic could map the drug trade's complexity but still had to resolve through personal moral choices. Syriana's sprawling critique of oil politics ultimately retreated into individual character arcs. Babel tried to suggest connection through parallel editing and cosmic coincidence, but its very production model - designed to appeal simultaneously to multiple national audiences while maintaining Hollywood production values - ended up reinforcing the power dynamics it hoped to challenge.

By the late 2000s, the genre's central tension had become impossible to ignore: these films wanted to show systemic issues but felt compelled to make them personal; they aimed to reveal real connection but relied on increasingly contrived coincidence. The beautiful lie began to unravel. The question was no longer whether everything was connected, but whether connection itself might be part of the problem.

A system built to blame its victims

The beauty of blaming everything on a butterfly in Brazil is that no one has to face the jaguar in their own backyard. Network films of the early 2000s mastered this sleight of hand, turning systemic guilt into a kind of shell game where responsibility constantly shifted but never quite landed. In Crash, wealthy housewife Jean Cabot's (Sandra Bullock) journey from paranoid racism to manufactured enlightenment through her Hispanic housekeeper Maria exemplifies this pattern perfectly. The film suggests structural racism can be solved through individual moral awakening, transforming centuries of systemic violence into a neat character arc about one white woman learning to hug her maid. Her eventual epiphany after falling down stairs – literally brought low by her own prejudice – reveals the genre's favorite magic trick. Transforming structural problems into individual moral dramas.

Syriana perfected this diffusion of responsibility through what scholars call 'neoliberal heroes' - fragmenting its narrative between Bob Barnes (George Clooney), the compromised CIA operative; Bryan Woodman (Matt Damon), the energy analyst whose personal tragedy entangles him in oil politics; and Prince Nasir, the reformist royal dreaming of democratic capitalism. Each character embodies a different facet of systemic corruption while remaining just sympathetic enough to deflect real criticism. The film's sprawling critique of oil politics required clear villains, yet even its most corrupt characters came equipped with humanizing backstories and reasonable motivations. When Barnes ends up tortured in a basement or Woodman watches Nasir's assassination, their individual suffering becomes a convenient substitute for addressing the systems that produced it.

This approach to localized guilt offered the comfort of specific antagonists while acknowledging systemic complexity. But the resolution followed a familiar pattern - characters either fled from the system's most intensive nodes (like Jeffrey Wright's lawyer escaping to the United States) or made ultimately futile attempts at reform (Barnes trying to warn Nasir about his impending assassination). The weight of guilt proved too heavy for any individual to bear, too dispersed to effectively challenge.

But the most insidious displacement of guilt emerged through what Tania Modleski calls "the hysterical text" - network films' unconscious tendency to make women bear the psychological burden of systemic failure. Crash's treatment of Christine (Thandiwe Newton) epitomizes this pattern. After being sexually assaulted by a racist police officer, she's later forced to accept help from her abuser when he pulls her from a burning car. The film frames her wordless gesture of forgiveness as a moment of grace, transforming systemic police violence against Black women into a personal journey of healing that demands nothing from the perpetrator. Her body becomes both the site of violence and the vehicle for redemption, reproducing ancient patterns of forcing women to absorb and absolve society's sins. In Traffic, Caroline's mother Barbara becomes the repository for guilt over her daughter's addiction. While Robert actively tries to address both personal and systemic issues, Barbara faces condemnation for her passivity and past drug use. The film tells us her liberal permissiveness enabled Caroline's downfall, reproducing ancient patterns of blaming mothers for society's ills.

Babel takes this gender displacement to baroque extremes through its treatment of Susan (Cate Blanchett). Her initial preoccupation with surface concerns - refusing local water, using hand sanitizer, maintaining her appearance - marks her as frivolously concerned with aesthetics while her husband Richard grapples with "real" issues. The underlining takeaway is that feminine superficiality must be violently purged through injury and humiliation before genuine cross-cultural understanding becomes possible. Even The Constant Gardener, which positions activist Tessa as its moral center, undermines her credibility by having male characters repeatedly question her sexual fidelity, as though uncovering pharmaceutical industry crimes somehow connects to personal virtue.

Richard: “Jesus Christ! Why can’t we just relax? Why are you

so stressed?”

Susan: “You’re the reason I’m stressed; you’re the reason I

can’t relax.”

Richard: “You could if you tried.”

Susan: “You don’t think I tried?”

Richard: “You’re never going to forgive me, are you?

Dialogue from Babel (2006)

This gendered displacement of guilt operated alongside broader cultural anxieties about masculine impotence in the face of global systems. Network films emerged as traditionally male spheres of influence - government, industry, military - seemed increasingly unable to affect meaningful change in an interconnected world. The genre's repeated focus on failed fathers, compromised executives, and impotent authority figures reflected deep uncertainty about agency in networked systems.

Yet rather than examining how patriarchal power structures might themselves perpetuate systemic problems, these films displaced responsibility onto women who supposedly enabled moral decay through their own weakness or vanity. The pattern reveals how even presumably progressive critiques of globalization often reinforced existing power dynamics in their attempt to resolve systemic anxiety.

Two films nuking the formula

While mainstream cinema spent the 2000s engineering increasingly elaborate collisions between characters, two films from 1999 had already mapped the outer limits of what network narratives could achieve. In one corner stood Magnolia, Paul Thomas Anderson's sprawling opus about intersecting lives in the San Fernando Valley. The film took the DNA of what would become network cinema's favorite tricks - parallel editing, cosmic coincidence, simultaneous crisis - and pushed them past the breaking point into genuine surrealism.

Its damaged ensemble of dying TV producers, coked-out former quiz kids, and imploding self-help gurus orbited each other with the gravity of Greek tragedy filtered through late-night infomercials. The film's three-hour runtime luxuriated in the kind of connections that later movies would reduce to quick-cut montages, letting its web of relationships unspool at a pace that made synchronicity feel earned rather than imposed. When divine intervention finally arrived in a rain of frogs (yes, actual frogs falling from the actual sky), it landed with the weight of genuine revelation rather than narrative convenience. Anderson understood something that later network films would work very hard to obscure - if you want to suggest everything is connected, you need to embrace the fundamental absurdity of that proposition.

And there is the account of the hanging of three men, and a scuba diver, and a suicide. There are stories of coincidence and chance, of intersections and strange things told, and which is which and who only knows? And we generally say, "Well, if that was in a movie, I wouldn't believe it." Someone's so-and-so met someone else's so-and-so and so on. And it is in the humble opinion of this narrator that strange things happen all the time. And so it goes, and so it goes. And the book says, "We may be through with the past, but the past ain't through with us."

Quote from the Narrator in Magnolia (1999)

Michael Haneke walked the opposite path through this same creative wilderness. Rather than amplifying coincidence into cosmic significance, Code Unknown stripped away every comforting pretense of meaningful connection. Its characters passed each other on Paris streets without discovering hidden links. Its scenes cut to black precisely when other films would manufacture moments of recognition. Even its most dramatic confrontations - like the metro sequence where Binoche faces escalating harassment - refused the satisfaction of clear moral resolution or character growth. The film's structure mirrored the experience of living in an interconnected world where genuine understanding remains elusive despite constant proximity. Fragments stayed fragmentary. Stories remained incomplete. The very title mocked our desire to crack some hidden code that would make everything make sense.

These divergent approaches - Anderson's maximalist embrace of artifice and Haneke's minimalist refusal of false connection - illuminated the limitations of how other network narratives tried to process systemic anxiety. Magnolia's rain of frogs worked better than Babel's magic bullet precisely because it admitted its own unreality.

Code Unknown's unresolved tensions felt more honest than Crash's manufactured epiphanies because they acknowledged how connection often fails despite our best efforts. One film pushed coincidence past the breaking point into genuine supernatural intervention, while the other stripped away every narrative comfort to expose the gaps between people that no amount of careful plotting could bridge. Together they charted alternate paths through the creative territory that mainstream network films tried so desperately to claim - one through radical embrace of artifice, the other through radical refusal of false resolution.

Between these two poles of maximalism and minimalism, the mainstream network narrative struggled to find stable ground. Film scholars, those dutiful taxonomists of cinematic trends, had neatly divided these films into two categories: "contingency narratives" (where random car crashes revealed our shared humanity) and "world-systems films" (where Matt Damon got very serious about institutional corruption). But both branches withered on the same dying tree.

The contingency crowd kept engineering ever more elaborate collisions, like a desperate party host convinced that if they could just get the right combination of guests to bump into each other by the cheese plate, world peace might break out. Meanwhile, the world-systems directors found themselves trapped in the same corporate labyrinth they were trying to expose - their ambitious maps of military-industrial complexity kept getting refolded into tidy personal journeys toward enlightenment.

A film could span continents tracking the tentacles of global capitalism, but eventually some disillusioned white guy in expensive leisurewear had to stare meaningfully into the middle distance and deliver a monologue about how everything was connected. The genre died doing exactly what it criticized - reducing vast systems to personal revelation, like a Victorian explorer convinced he could comprehend the entire British Empire by having one really good eureka! moment about tea.

Everything's a psyop when you're terminally online

The cosmic rain of frogs in Magnolia landed in 1999. Twenty-five years later, we're scanning the skies for something darker - CERN's particle accelerator firing up during a total solar eclipse, NASA launching satellites named after Egyptian snake gods, red heifers being sacrificed in Jerusalem. The evolution from finding meaning in coincidence to suspecting conspiracy in connection marks a fundamental shift in how we process our entangled world. Those early network narratives offered a liberal humanist fantasy - that our global collisions might yield enlightenment rather than paranoia. Now even the path of the eclipse gets mapped as a connect-the-dots through American trauma, linking presidential assassination sites to chemical spills to government massacres. The pleasant fiction of meaningful connection has curdled into universal suspicion.

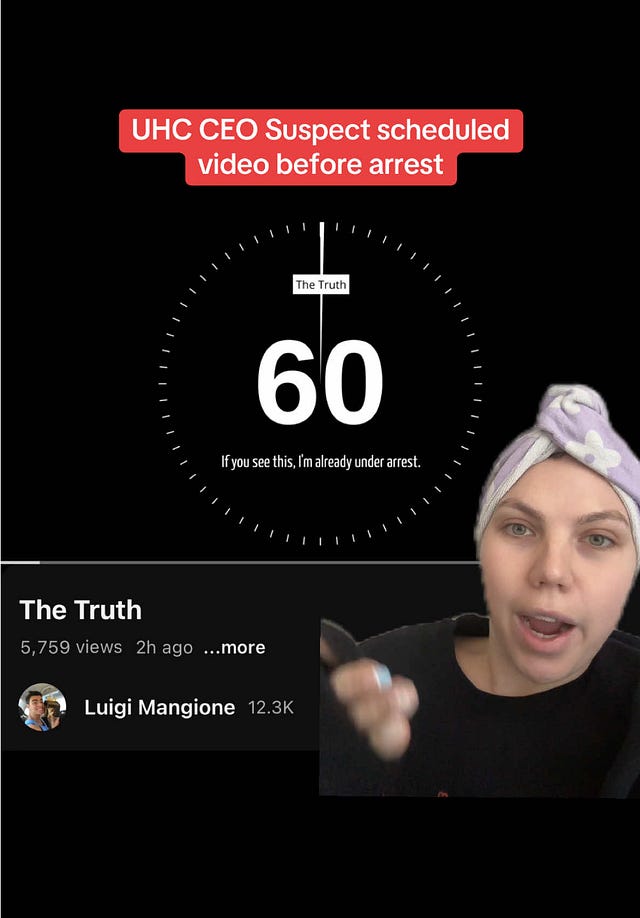

This transformation runs deeper than just increasing cynicism. When United Healthcare's CEO was gunned down in Manhattan earlier this month, social media didn't just speculate about motives - it constructed an entire alternative narrative around shell casings allegedly inscribed with insurance industry jargon. The "three Ds" of claims denial (delay, deny, defend) transformed into ballistic evidence, manufacturing meaning from corporate bureaucracy with the same determination that network films once used to extract epiphanies from car crashes.

But where Babel strained to suggest that a single bullet could reveal our shared humanity, contemporary pattern-recognition seeks to expose systems of control. Luigi Mangione’s surprisingly photogenic face sparked not just memes but elaborate theories about staged events and crisis actors. We've traded Crash's forced redemption for what cultural critics now call "Psyop Realism" - an aesthetic movement built around heightened awareness of propaganda and subversion in everyday life.

The structure of the internet itself encourages this conspiratorial mindset. As anthropologist Kathleen Stewart noted, the Web's architecture of endless hyperlinks naturally feeds the three cardinal rules of conspiracy thinking:

nothing happens by accident,

nothing is as it seems,

and everything is connected.

But this affinity has evolved beyond just making conspiracy theories easier to produce and consume. Social media's algorithmic architecture creates filter bubbles that feel like personally curated investigations rather than manufactured echo chambers. This paranoid pattern-recognition now pervades culture at every level. When Virginia Sole-Smith suggests parents need not restrict their children's food choices, the internet erupts in predictable fury - over 1,700 Washington Post commenters decrying her as anti-science, as if letting children learn to trust their own appetites amounts to societal collapse.

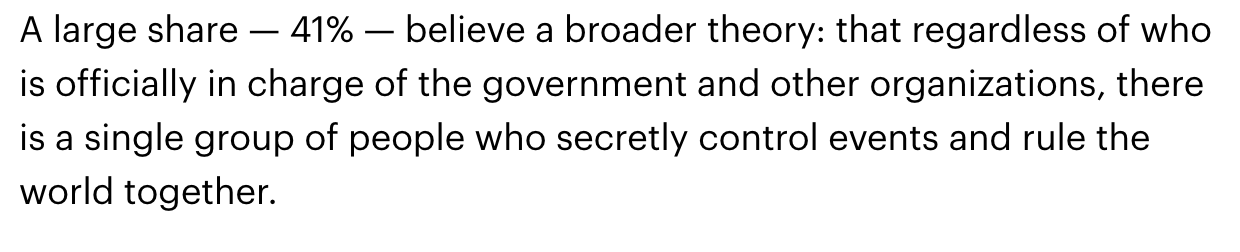

Each revelation reinforces what cultural theorist Mark Fisher termed "the weird and the eerie" - the creeping sensation that seemingly natural phenomena are actually orchestrated by hidden forces. A 2023 YouGov poll found 41% of Americans believe a single group secretly controls world events. The percentage rises among both the very wealthy and very poor, suggesting that economic precarity at either extreme breeds suspicion rather than solidarity.

The bitter irony is that this evolution simply inverts rather than escapes network narratives' original sin. Where films like Syriana used coincidence to make systemic issues feel personally manageable, contemporary conspiracy thinking deploys the same techniques to identify convenient villains. Both approaches avoid confronting the genuine horror of systems that operate without central control or clear antagonists. As political scientist Michael Barkun notes, conspiracy theories began shifting in the 1960s from imagining tight-knit groups of plotters to vast impersonal systems. Yet we still anthropomorphize these networks, reimagining institutional forces as intentional agents because the alternative - that no one is truly in control - feels even more terrifying.

This might explain why Code Unknown's refusal of false connection resonates more strongly now than when it was released. Its fragments and ellipses mirror our contemporary relationship with truth - always partial, constantly slipping away, resistant to both conspiracy and comfort. We're all amateur semioticians now, searching for meaning in every cultural artifact while simultaneously suspecting that meaning itself might be a psyop. The fascinating horror of our moment isn't that everything is connected, but that we can't stop trying to connect everything, even as we trust connection less and less.

Meaning-making as mass delusion

Something shifted in us between Magnolia's divine intervention and this month's conspiracy-laden breaking story. The fantasy of meaningful connection - that comforting lie of early 2000s cinema - has given way to endless pattern recognition without purpose. I keep thinking about those shell casings at the United Healthcare shooting, inscribed with corporate jargon like some twisted art installation. We don't need Hollywood manufacturing coincidences anymore. We're too busy constructing our own labyrinths of meaning, each new cultural moment another dot to connect in an increasingly desperate search for order.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Those early network films, for all their forced coincidences and manufactured revelations, at least betrayed a kind of desperate optimism. They emerged when "bearing witness" still felt like a revolutionary act, when the spectacle of suffering might somehow yield transformation rather than content. Traffic's Robert Wakefield could retreat into private rehabilitation, The Constant Gardener's Justin could die exposing pharmaceutical corruption, Hotel Rwanda's Paul could save his refugees - each protagonist discovered their impotence and promptly transformed it into the kind of personal journey that wins awards. Their failures were perfectly calibrated for more empathy and less systemic change, converting global catastrophe into individual character development with the precision of a corporate retreat. Now our failures are algorithmic, our revelations pre-formatted for maximum engagement, our very awareness of disconnection repackaged as proof of our entanglement in systems we can analyze endlessly but never escape.

The machinery of contemporary capitalism has evolved beyond those clumsy early attempts at displacement, perfecting a form of alienation that makes disconnection feel like empowerment. Women still shoulder the psychic burden of systemic failure, but now through an infinitely more sophisticated mechanism - every woman artist an industry plant, every cultural contribution evidence of manipulation, every success story proof of shadowy backing. The same patriarchal anxieties that once required elaborate narrative gymnastics now reproduce automatically, turning even resistance into content. The weight of unresolved guilt presses down harder than ever, but we've lost the ability to feel its pressure without suspecting manipulation.

Our networks have perfected what those early films could only gesture at - the transformation of systemic violence into personal narrative. But where Traffic strained to make the war on drugs intimate through a judge's daughter's addiction, our current systems excel at making intimacy itself feel systemic. Each attempt at genuine connection arrives preemptively corrupted, suspected of being engineered even as we engage with it.

We've traded magical neoliberalism for magical thinking of a darker sort, replacing forced epiphanies about shared humanity with equally forced cynicism about shared complicity. The rain of frogs at least announced itself as divine intervention. Our current networks operate through a more insidious magic - one that transforms even our suspicion into proof of its power.

I find myself returning to that moment when everything changed, when we stopped expecting connection to save us and started suspecting it might be the thing we needed saving from. The systems we built to bring us together now excel at keeping us apart, not through elaborate conspiracies but through mechanisms so ordinary they've become invisible. We map eclipse paths through tragedy because facing our actual condition - genuine disconnection within systems designed to simulate its opposite - requires admitting that no hidden code will make sense of what we've built.

The weight of this realization changes everything it touches. Even the sky above us becomes another text to decode, another pattern to map. Generation by generation, we've perfected a peculiar form of loneliness - one that mistakes endless analysis for genuine understanding, forever searching for meaning in the very mechanisms designed to keep us searching. The true brilliance of modern capitalism isn't that it built systems to keep us apart - it's that it convinced us finding the right pattern might somehow bring us together.

P.S. Apparently hitting that little heart button is the equivalent of leaving a good tip for the algorithm™ gods. So if you enjoyed reading this, please give it a like.

A final note for people with taste 🫦

While the internet's prioritizing hot takes and SEO-optimized nothingness, I’m trying to building something genuine here: a sanctuary for people who actually give a damn about films and television.

For the price of a truly mediocre sandwich, consider joining the resistance with a paid subscription – it keeps independent film writing alive and the algorithms at bay.

Plus, you'll get exclusive access to After Credits, my monthly handpicked selection of films & television that will make your brain do the happy chemicals AND save you a bunch of time.

Now go forth and raise those standards, darling.

- Sophie x

Interesting retrospective.

I've always liked "systems novels" (Pynchon, Delillo, Stephenson) but I've never liked those global interconnectedness movies. I never even considered their similarities or differences until this article.

Crash really bothered me right from the get-go. I think it's right in the first scene that the dialog posits "In LA, a car crash is the only way we can touch each other" which stank of writerly metapoetics rather than actual experience. I have the same problem with both Haggis's AND Cronenberg's Crashes: vehicular accidents are NOT INTIMATE AT ALL. Not even metaphorically. Not poetically. That said Cronenberg's Crash I have a whole different discussion about.

I think my biggest takeaway from your various topics in this one essay is that there is a sublime need to an arts and politics of agency. The only solutions are agentic ones, but people are rather tired in their lack rather than focused on creating agency.

This is a fantastic piece of analysis and criticism.