scorsese and my therapist agree

How I spent £9,000 on therapy to learn what Scorsese had been telling me through whip pans and Rolling Stones songs.

My therapist and Martin Scorsese spent years trying to tell me the same thing: that goodness isn't what I thought it was. My therapist did it through careful silence and pointed questions. Scorsese did it through Catholic guilt and tracking shots. It took me three years of therapy and two decades of watching his films to finally understand what they meant.

"Sometimes," my therapist said during one of our early sessions, uncrossing her legs and leaning forward in that way therapists do when they're about to ruin your whole week, "we confuse being good with being convenient for others." The kind of statement that makes you want to crawl out of your skin, or at least pretend your phone is ringing and leave therapy early. But there it was, hanging between us like a verdict.

Good girls make terrible protagonists

The first time I watched Mean Streets in my mid twenties, I sat in my cramped London flat, takeaway containers creating a fortress around me, and thought it was about loyalty. About Charlie trying to save Johnny Boy, about doing the right thing. It took two years of therapy - and approximately £9,000 in South London therapist fees - to realize what Scorsese was actually showing us: how salvation and self-destruction wear the same face, especially when you're raised on a cocktail of cultural Catholic guilt or, in my case, its Greek Orthodox cousin. Charlie's movement between the neon-red bar and the sacred quiet of church isn't just Scorsese's signature visual dialectic - it's the exhausting choreography of someone trying to reconcile who they are with who they're supposed to be. The camera stalks him through these spaces like an uneasy conscience, never letting him settle into either world completely.

Being the third child in a Greek family means you learn this choreography early. You become fluent in the language of expectations before you can even speak. Sunday lunches in our Athens home were award-winning performances - my mother's hands moving across the blue and white tablecloth with the same nervous precision that Scorsese captures in his signature tracking shots. Understanding everything, fixing everything, being everything – these weren't just expectations, they were survival strategies. Between bites of spanakopita and carefully measured silences, I watched my sisters navigate their assigned roles - the savior and the rebel - while I perfected my part as the medium shot between extremes, the steady-cam operator of family harmony1.

"Your constant need to be good," my therapist said during one particularly brutal session, her voice gentle but unflinching, "is its own kind of violence." The words hit like one of Scorsese's quick zooms to a character's face right before their world implodes. In Greek families, we're taught that goodness is next to godliness, but Scorsese understands what my therapist was trying to tell me - sometimes godliness is just another word for self-erasure. I thought about how in Taxi Driver, it's not the actual violence that's most disturbing - it's those moments when Travis stares at himself in the mirror, rehearsing who he thinks he needs to be. The layers of performance so thick they become reality.

The way Scorsese frames violence - quick, brutal, but somehow inevitable - reminds me of how cultural expectations can wound. In Mediterranean families, we don't need baseball bats or guns; we have raised eyebrows over coffee and carefully curated photo albums that tell the story of who we're supposed to be. My mother's photo albums are arranged in meticulous attention - every image carefully selected to construct a narrative of perfect family synergy. The violence isn't in the blow, but in the thousands of tiny cuts that shape you into someone more digestible for public consumption. It's in the way my sister's biology degree became a "phase" in family conversations, in how my mother still introduces me as "the one who got a Distinction at uni" rather than "the one who writes about films."

Trying to save everyone is another form of running away

The thing about watching Bringing Out The Dead post-therapy is that you start seeing your ex-therapist's greatest hits everywhere. Scorsese's camera follows Nicolas Cage's Frank Pierce through New York's streets in long, unbroken takes - the same way my mind used to race through endless loops of other people's problems. Those signature Scorsese frames, fluid but relentless, mirror the exhausting momentum of trying to save everyone. My version played out in a flat in Wandsworth with significantly less cocaine (none, actually) but the same suffocating need to fix everything, save everyone, be the solution to problems I hadn't even been asked to solve2.

"What would happen," my therapist asked during one session, her voice cutting through my rapid-fire list of weekly accomplishments and obligations, "if you stopped trying to be good?" The question hung in the air like smoke in a Scorsese wide shot. She let the silence stretch, a technique Scorsese himself might appreciate - the way he holds on faces a beat too long, pushing past performance into raw truth. I pressed my fingernails into my palms until they left marks, thinking about how my mother's perfectionism had become my own personal prison, how my sisters' paths had somehow become my roadmap, how every family gathering felt like a scene from Casino - everyone performing their roles with such practiced resilience that we'd forgotten it was a performance at all.

During one particularly exhausting week of being everything to everyone, my therapist said something that cracked my chest open: "Performance is a form of hiding. Even perfect performance." I thought about how Scorsese frames those fantasy sequences in King of Comedy, letting them bleed into reality until we can't tell the difference anymore. How Rupert Pupkin's delusions feel less like madness and more like survival strategy. My therapist called it "maladaptive coping." Unfortunately, it works - until it doesn't. Like how Scorsese's characters always think they've got the system beat until the system beats them back. Every Sunday dinner was another performance where I'd walk the highwire between authenticity and acceptance, thinking I was pulling it off, never realizing that the audience could see the trembling in my hands the whole time.

It wasn't just me seeing these patterns anymore. Like that virtuosic shot through the Copacabana in Goodfellas, once you notice it, you can't look away. I started recognizing it everywhere: in my dad's constant need to keep busy with 'chores he can't get away from' (classic avoidance, my therapist would say), in my sister's careful curation of the burnout aesthetic (Scorsese would approve the production design), in my own exhausting pursuit of some impossible standard of Greek daughter excellence. The family dynamics playing out like a perfectly choreographed scene where everyone knows their marks but nobody remembers who wrote the script.

The close-up doesn't lie

Here's what Scorsese understands about Catholic guilt that my therapist understood about Greek family dynamics - the real violence isn't in the explosion, it's in the anticipation. It's why his camera doesn't just capture moments, it stalks them. That slow dolly in Mean Streets when Harvey Keitel walks into the bar, the camera following like an uneasy conscience. Some would call it a director’s style but I see it as psychological excavation3. Both Scorsese and my therapist understood that the real story lives in the spaces between what we're willing to show and what we're desperate to hide.

My therapist deployed the same technique through silence. Early sessions felt like those claustrophobic Scorsese close-ups - nowhere to hide, no quick cuts to save you. "Notice what happens when you sit with discomfort," she'd say, while I squirmed under the weight of my own gaze. Like Travis Bickle practicing his lines in the mirror, except my audience was a therapist with immaculate posture and a talent for weaponizing silence. The thing about both therapy and Scorsese films is that they're obsessed with patterns. Remember how Henry Hill in Goodfellas repeats his father's mistakes while convincing himself he's different. The camera swooping and swirling around him like fate itself, each tracking shot a perfect circle of repetition. My therapist called this "intergenerational patterns." Scorsese calls it storytelling. And I call it Thursday nights at my parents' house4.

"We often recreate what we're trying to heal," my therapist said once, after I'd spent twenty minutes describing my elaborate systems for managing everyone else's emotions (we debated if I should use a spreadsheet or not). The same week, I rewatched Casino and finally saw what Scorsese was doing with Sharon Stone's Ginger - how her desperate clutching at money and control was really just a child's fear of abandonment dressed in sequins. The way he films her counting room scenes like a church confession, the money sliding through her fingers like rosary beads.

Scorsese's later films get quieter, more contemplative. The Irishman isn't about the violence of bullets but the violence of time, of choices, of the stories we tell ourselves. My therapist would appreciate how he lets De Niro's Frank Sheeran sit in that nursing home chair, the camera steady and unflinching, as he faces the emptiness he's spent a lifetime trying to fill. Sometimes healing looks like finally letting the camera catch you exactly as you are5.

Perfect performance is perfect prison

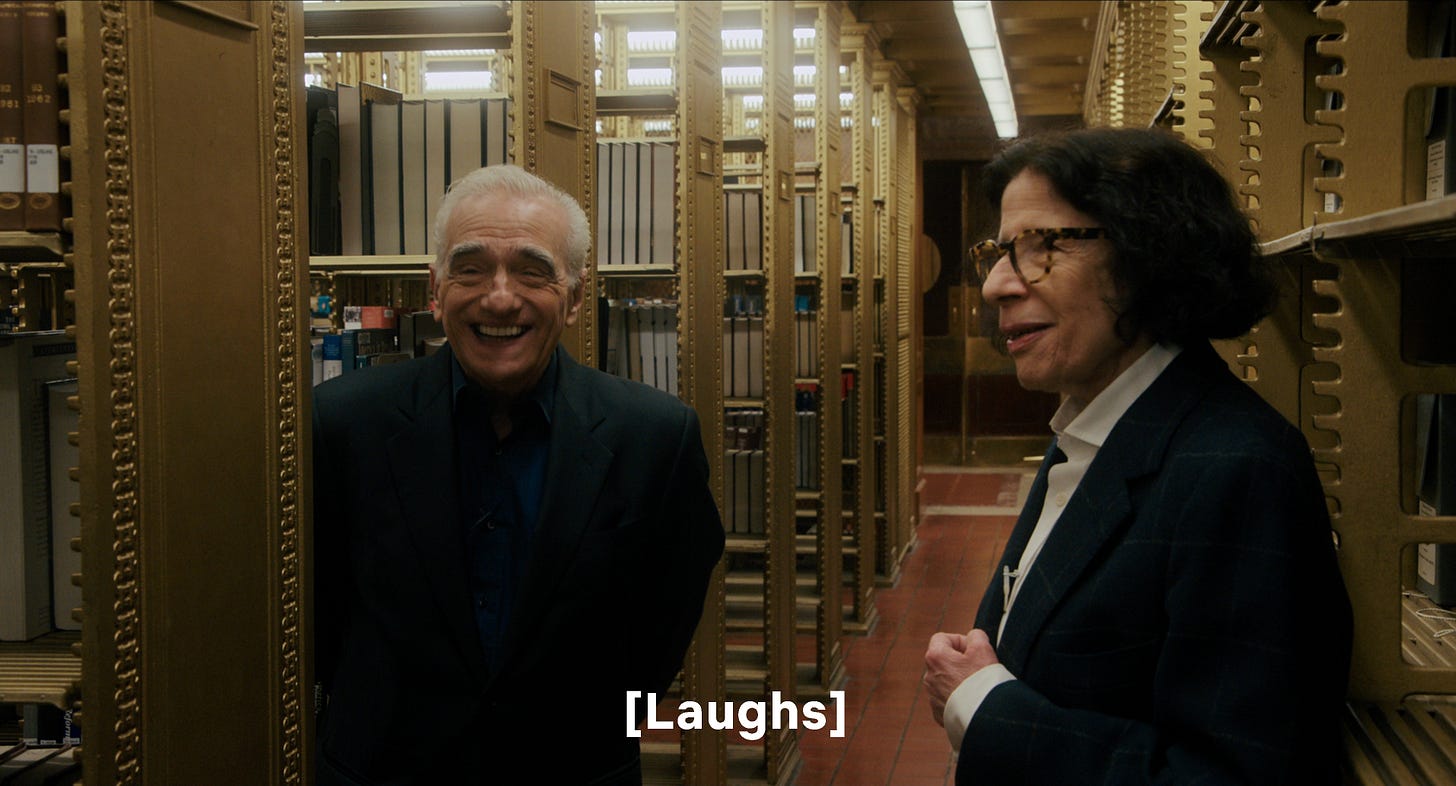

In Pretend It's a City, Fran Lebowitz tells Scorsese, "I'm not successful, I'm lucky - there's a difference6." His laugh in response isn't just delight - it's recognition. You can hear decades of Catholic guilt dissolving in that sound, the same way my nervous laughter in therapy started softening into something more genuine. Watch Scorsese's later films and you'll see a similar transformation - the frenetic energy of Goodfellas giving way to the measured contemplation of Silence, the quieter but no less profound wrestling with faith and identity. It's the same evolution my therapist witnessed in me, from rapid-fire deflections to actually sitting with discomfort.

Recently, during a family dinner, my mother was doing her usual dance of overdelivering - rearranging plates, adjusting portions, orchestrating harmony through controlled chaos. I watched her hands move with a careful calibration between love and control. But something was different this time. Maybe it was the three years of therapy, or maybe it was all those hours spent studying Scorsese's frame compositions, but I finally saw what both had been trying to teach me about negative space - sometimes what's not being said is more important than what is.

The mushroom risotto sat in the center of the table like one of Scorsese's religious artifacts in Mean Streets - something sacred and complicated. My mother adjusted its position three times, her movements echoing the way the camera circles Jack LaMotta in Raging Bull, both hunter and hunted. "Mama," I said, using the Greek that always sounds softer than English, "it's perfect as it is." She stopped, hands hovering mid-adjustment. In Scorsese's films, these are the moments he holds on - when the performance cracks and something real bleeds through. When Travis Bickle's practiced smile slips, when Henry Hill's cocaine-fuelled confidence falters.

"Your mother's perfectionism," my therapist had said months earlier, "isn't a command to be followed. It's a wound asking to be witnessed." The words came back to me as I watched my mother's hands finally settle in her lap, the way Scorsese's camera sometimes finds stillness after chaos. In The Irishman, the camera doesn't chase action anymore - it waits, observes, lets truth surface in its own time. I thought about how both Scorsese and my therapist had taught me the same lesson: often times the most profound act of love is simply bearing witness.

Letting boring win is a radical act

The last time I saw my therapist, I spent ten minutes talking about the weather. Not my usual performance art piece about being Everyone's Emotional Support Person™, not my greatest hits compilation of Weekly Achievements in Being Good. Just... London weather. Grey, drizzly, perfectly boring London weather. She didn't say much. She didn't need to. Like Scorsese's best endings, the real catharsis wasn't in what was said, but in what finally didn't need saying anymore.

I keep thinking about the end of The Age of Innocence, how Scorsese lingers on Daniel Day-Lewis’ Newland Archer sitting outside Michelle Pfeiffer’s Countess Olenska's apartment in Paris, choosing not to go up. The camera holds steady on the space between desire and duty, between who we are and who we've learned to be. It's the kind of ending that would have frustrated me before - all that build-up for someone choosing not to act? But now I understand what both Scorsese and my therapist were trying to show me: sometimes the most courageous shot is the one where nothing (extraordinary) seems to happen.

I don't go to therapy anymore, but Scorsese's films keep doing the work. Late at night, I find myself back on that grey couch, watching Alice Hyatt (Ellen Burstyn) singing in that dive bar, raw and unpracticed but finally, devastatingly herself. Rupert Pupkin alone in his basement, when the applause track cuts out and there's just silence. Sam 'Ace' Rothstein, staring at himself in the mirror while putting on his suits in that montage - each one another layer of armor that won't protect him anyway. All these moments land differently now - not because they're more meaningful, but because I finally understand what both Scorsese and my therapist were trying to tell me: that the most violent thing we do to ourselves is pretending to be who we think we should be, instead of who we are.

And the most courageous thing? It's letting the camera roll anyway. Even when - especially when - we don't know our lines7. Sometimes the steadiest shot is the one that captures us exactly as we are: imperfect, unfinished, still in production.

P.S. Apparently hitting that little heart button is the equivalent of leaving a good tip for the algorithm™ gods. So if you enjoyed this essay, please give it a like. And if you're sharing any of these takes in the wild (bless you), tag me - I love seeing which parts made you go "YES FINALLY SOMEONE SAID IT." Links are also deeply appreciated because, you know, sharing is caring and all that cinema-loving jazz.

The irony of a Greek family using silence as a weapon would not be lost on Scorsese's Catholic sensibilities.

Though at least Frank Pierce got a cool ambulance. All I got was chronic high-functioning anxiety and a concerning ability to function on four hours of sleep.

The 180-degree rule exists to be broken, just like defense mechanisms. Both my therapist and Scorsese taught me that.

Though if we're being honest, my family drama's soundtrack is less "Gimme Shelter" and more "Zorba the Greek" meets existential crisis.

The nursing home scenes in The Irishman cost millions to make. Therapy in London costs about the same.

Possibly paraphrazing this quote. It’s been a while since I’ve seen this brilliant doc.

If Scorsese reads this, I hope he appreciates how I ended on a moral revelation without resorting to voice-over. My therapist would be proud.

I have a feeling you're also a Sopranos fan. Fantastic piece -- although even you couldn't convince me that Mean Streets isn't overrated.

Sophie, this piece hits so close to home for me—it's uncanny. Like you, I've found myself unpacking years of tangled expectations and ideals, not just in therapy, but in those deeply personal conversations films seem to hold with us. There's something revelatory in his framing of characters who grapple with internal prisons of 'goodness,' a quiet violence against self that resonates all too well.

Your words bring out a truth that’s been my own therapy too: realizing that we’re not obligated to perform ourselves into corners of convenience for others. Scorsese’s films are like mirrors, both brutal and comforting, in how they linger on the rawness of these realizations. Thank you for putting into words what so many of us feel but rarely find ways to express—about family, self-worth, and the quiet liberation of letting go. It’s healing in itself to read this, and I’m grateful you shared it.