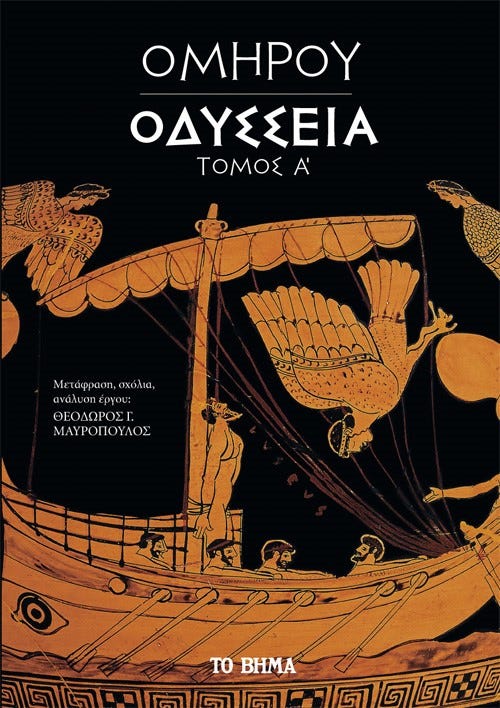

everything i need from christpher nolan's odyssey (an extremely greek perspective)

Three thousand years of Greek inheritance, and all it took was one IMAX camera to make me question who stories really belong to.

My relationship with Odyssey1 manifests in three distinct forms:

what was forced upon me in that sweltering Athens classroom,

what I absorbed through cultural osmosis in the decades since,

and what I'm now watching Hollywood attempt to reshape into their latest exercise in classical devastation.

The text requires a particular type of engagement from its reader, one that my high school teacher understood better than most. Her wire-rimmed glasses caught the afternoon light as she tapped the weathered copy of Odyssey. "Poetry," she declared, "requires ακρίβεια." In Greek, that word carries the weight of centuries — it demands exactness, perfection, truth that cuts like a blade. Though it also means 'shit is expensive!' which feels cosmically appropriate given what I'm about to tell you about Sir Christopher Nolan's newest venture.

Odyssey followed me out of that classroom and into the streets of Athens like an intellectually transmitted disease, infiltrating every corner of my adolescent existence. My classmates and I absorbed Homer's verses with the same inevitability as the city's dust and diesel fumes. Resistance was futile and complete surrender was the only option.

For my generation, Homer2 wasn't just another dead white guy haunting the curriculum (though he very much was that too). His work possessed us with the persistence of a particularly determined poltergeist, manifesting in our gestures when we argued about anything from playground politics to market prices, our voices unconsciously channeling his rhythms. We were teenagers in Athens, and Homer had colonized our entire framework for understanding the world whether we liked it or not.

These memories surfaced with surprising clarity when Universal Pictures announced Christopher Nolan would direct The Odyssey, described in their press release as a "mythic action epic." The phrase landed like a discordant note in an otherwise familiar melody. In Greek, we have a word for this too - παραφωνία - literally "beside the voice," when something is almost but not quite right.

Because Odyssey has never been about action, not really.

It's about time and memory, about how ten years can feel like both an eternity and a heartbeat, about how home becomes an abstract concept rather than a GPS coordinate when you've been away too long. When Odysseus finally returns to Ithaca, his old dog Argos, weak and neglected after years of waiting, recognizes his master through his disguise and then dies. Heartbroken yet finally at peace. This is Homer's world, honey. Absence accumulates like compound interest, and life steamrolls forward while you're out there chasing your destiny and trying to avoid being turned into swine by extremely otherworldly witch-goddesses.

My relationship with Odyssey has evolved from those classroom days, through years of watching films and writing about how stories translate across mediums and cultures. Each time I return to it, I find new layers of meaning, new threads to pull. But Greek holds meanings English can only circle, like a shark afraid of commitment. Certain words carry entire worlds that resist translation:

μῆτις flows through Odysseus's blood — wisdom earned through suffering, intelligence that borders prophecy, survival instinct elevated to art. Think Jason Bourne meets Gandalf (Mediterranean’s version).

νόστος haunts every homecoming — the price we pay for transformation, the way return becomes impossible once we've changed too much. It's that feeling when you visit your hometown and your favorite diner is now a Sweetgreen (or the UK equivalent, Tossed or something).

I've found myself straddling two conflicting emotional states since Nolan's adaptation was announced. Equal parts anticipation and apprehension. His filmography clearly reveals a director OBSESSED with time (Memento, Inception, Interstellar) but also the weight of return (The Prestige, Dunkirk). In theory, he is uniquely suited to capture the temporal gymnastics of Homer's epic.

But watching Hollywood's endless parade of sword-and-sandal spectacles has long taught me that the gap between reverence and entertainment isn't as simple as Athens versus Los Angeles. It's about what we choose to preserve, what we allow to evolve, and what gets lost when you try to translate poetry about fate and divine punishment into something that can sell popcorn.

Now Nolan stands at this crossroads, armed with IMAX cameras and a $250 million budget, ready to attempt what countless others have tried before:

Can he convince the world that an ancient meditation on time, memory and homecoming deserves the same technical precision as nuclear physics?

epic adaptations and other greek tragedies

The “greatest story ever told” is about a man who refused cartography — or at least that's what 108 writers and academics declared in 2018 when they crowned Odyssey above Orwell's warnings, Shelley's monsters, and every other narrative that rewired human consciousness. Not a single Greek judge on that panel (lol), a fact that would be deliciously ironic if it wasn't so predictable. The West loves to claim the classics, but rarely gives the descendants of their creators a voice in the conversation. And yet. They stumbled into truth anyway. This epic possesses an infinite half-life, radiating meaning long after its original context has crumbled into dust.

My teacher, who'd earned her perpetual existential fatigue after three decades of making teenagers care about hexameter, understood Homer as literature's first methodological anarchist. Odyssey is a decade of supernatural wandering after Troy detonates across 12,110 verses (a number I had to memorize or forfeit my place in third-year classics). Gods playing chess with mortal lives. Monsters that exist simultaneously as flesh-eating horror shows and walking philosophical propositions. Nothing says "let's examine the human condition" quite like forcing your protagonist to do catastrophe calculus between Scylla and Charybdis.

Baby, this isn't your standard hero's journey.

This is Homer grabbing narrative convention by the throat and saying "watch this."

His true insurrection wasn't plot but architecture. He begins with his hero stranded on a nymph's island, peak classical hubris getting its comeuppance, then proceeds to absolutely demolish linear time itself. Through an interwoven labyrinth of flashbacks, divine tea spilling, and narrators who wouldn't know the truth if it bit them on the bum, we piece together both journey and void. What does a decade of absence carve into a marriage? Into a child? Into a kingdom? While Penelope turns women's work into psychological warfare, Telemachus wanders the Mediterranean chasing paternal phantom. The gods watch from their cosmic balcony seats, debating free will versus fate like the world's first philosophy department, tenure guaranteed.

Many filmmakers have attempted to capture it all, with results ranging from revelatory to catastrophically misconceived. The 1950s presented Kirk Douglas in Ulysses, achieving somewhat genuine psychological depth despite the period's post-war propensity for martial pageantry. Giuseppe de Liguoro's 1911 L'Odissea transformed silent film's constraints into narrative advantages — his practical effects more philosophically coherent than any subsequent CGI spectacle.

Then arrived Troy (2004). Reader, here comes a confession so mortifying it might require a trigger warning. For an extended period of my adolescence — a period I'd prefer to attribute to temporary insanity — I had this film on repeat. It was one of those rare instances of "representation matters" that had my pubescent brain doing somersaults. "Hollywood finally cares about Greek mythology!" I probably squealed, while simultaneously doodling Achilles in the margins of my history notes. Ah, the folly of youth. Because knowledge, as we all eventually discover, is a poisoned chalice, and growing up means watching your childhood heroes get unceremoniously defaced like a poorly-maintained Caryatid.

Brad Pitt's Achilles, sculpted like a Michelangelo David with a spray tan, certainly redefined the aesthetics of Bronze Age combat. But the film's methodical eradication of the divine? That, my friends, was a cinematic sin far more unforgivable than simply butchering the source material.

One thing you need to understand about Greek literature and mythology is that gods aren't narrative ornament. They're the metaphysical operating system beneath every human choice. They're the original uncertainty principle incarnate. The 2010’s Clash of the Titans remake doubled down on this emptiness, turning rich mythology into a mindless CGI monster mosh pit. (Even the 1997 television adaptation, despite rendering Mount Olympus indistinguishable from provincial theater's greatest hits, grasped this essential truth.)

Fast forward to today. 2024's The Return, starring Ralph Fiennes and Juliette Binoche, attempted a course correction — or so I've heard. ( I haven't actually subjected myself to this cinematic endeavor yet as I’m waiting for the UK release). Word on the street – or, more accurately, whispers from my film critic comrades – is that it does try to isolate the epic's denouement to mine the psychological depths of homecoming. But apparently, it misses the mark by, you know, neglecting the whole "compelling characters" thing, which, last I checked, is kind of essential when adapting a story about a dude's decade-long journey home.

Which leads us to a far more intriguing question: Is the issue truly a lack of fidelity to the source material? No, I don’t think so.

I believe the real enigma is this:

Which slivers of Homer's epic universe do film studios and filmmakers deem worthy of their contemporary audiences?

What narrative morsels are deemed palatable, digestible, or even recognizable to the modern cinematic palate?

even bob dylan wants a piece of homer

History repeats itself first as preservation, then as controversy. In the 6th century BCE, Athens initiated one of civilization's earliest efforts to preserve texts, ensuring that works like Odyssey were meticulously safeguarded. Today, the epic remains a lightning rod for cultural debate. Movements like #DisruptTexts, founded in 2019, aim to diversify school curricula and rethink the traditional canon, sparking discussions about the relevance of classical texts in modern classrooms. And while advocates emphasize critical engagement over removal, misunderstandings about the movement have fueled controversy, often overstating claims of "banning" Homer.

My teacher would have savored this particular taste of drama (though she'd probably note that controversy has always swirled around these verses like wine in a kylix). Even in antiquity, critics like Zoilus of Amphipolis earned nicknames (“Homeromastix“ / “Ομηρομάστιξ“) for daring to question the epic's authority. Three thousand years of readers, and we're still arguing about what it all means.

Upon researching this essay, I found this incredible example of Homerists critiquing other Homerists:

“While I wholeheartedly agree with the essence of Fogagnolo’s analysis, I believe that what makes this passage especially susceptible to Zoilus’ criticism is the fact that Homer has Hermes voice his sexual desire for his half-sister in front of their father! It is almost as if the poet forgot the nature of the relationship between the characters when composing this tale.”

Absolute scenes.

The text deserves this scrutiny, of course, particularly regarding its treatment of women. For every moment of startling feminine agency - and there are many - Homer's epic reflects the patriarchal structure of its time. Women become prizes of war, objects of exchange value. Yet within these constraints, the female characters operate with remarkable complexity. Women like Penelope wield μῆτις, a word that English flattens to "cunning" but actually encompasses an entire ecosystem of intelligence, wisdom, and tactical thinking.

The divine women inhabit an even more fascinating space. Circe and Calypso wield power that makes heroes tremble, yet their stories often get reduced to simplified temptress narratives. In the Greek text, Circe, a woman without a κύριος aka a man), emerges as a master of μεταμόρφωσις - not just physical transformation but fundamental change in nature. Her pig spell reads less like magical mischief and more like divine commentary on human nature. (What better way to reveal a man's inner beast than turning him into one?)

Calypso, meanwhile, offers Odysseus the ultimate escape from patriarchal expectations: immortality itself (just ask Jeff Bezos). His rejection of divine love for mortal marriage becomes less about fidelity and more about choosing human complexity over divine perfection. All while the gods watch from Mount Olympus, eating their popcorn and placing their bets.

The gods themselves deserve closer reading than Hollywood's tendency to treat them as particularly dramatic weather events. When Athena shrouds Ithaca in mist upon Odysseus's return, the Greek word ἀχλύς suggests something far beyond atmospheric conditions. This is the disorientation of homecoming itself — the way time and distance transform both returner and returned-to beyond recognition.

I think about this every time I visit Athens. The city simultaneously exists as my childhood memory and as its current reality, both versions somehow equally true and equally false. Every immigrant who has ever found their hometown simultaneously familiar and foreign knows this particular flavor of divine pranking.

This interplay between transformation and disorientation reverberates beyond mythology into modern storytelling. In Bob Dylan’s Nobel lecture (sent to the academy with an audio link in which he reads aloud), between namedropping Proust and confessing to drinking problems —academic cosplay this is not— he dismantles six millennia of scholarly pretension.

In the following excerpt, he points at our spectacular capacity for self-sabotage and said 'same’:

“In a lot of ways, some of these same things have happened to you. You too have had drugs dropped into your wine. You too have shared a bed with the wrong woman. You too have been spellbound by magical voices, sweet voices with strange melodies. You too have come so far and have been so far blown back. And you’ve had close calls as well. You have angered people you should not have. And you too have rambled this country all around. And you’ve also felt that ill wind, the one that blows you no good. And that’s still not all of it.”

Dylan gets it because he's lived it. When you realize you're 'one against a hundred' and your only way home is through yet another transformation, another identity shift, and another story that needs telling, you know what that feels like. Dylan continues:

“When Odysseus in The Odyssey visits the famed warrior Achilles in the underworld – Achilles, who traded a long life full of peace and contentment for a short one full of honor and glory – tells Odysseus it was all a mistake. “I just died, that’s all.” There was no honor. No immortality. And that if he could, he would choose to go back and be a lowly slave to a tenant farmer on Earth rather than be what he is – a king in the land of the dead – that whatever his struggles of life were, they were preferable to being here in this dead place.”

Three thousand years of tenured professors scribbling about heroic ideals, and it takes the guy who went electric at Newport to point out the primitive human talent for turning our catastrophes into songs worth singing.

nolan 🤝 homer: control freaks, a love story

And so we arrive at Sir Christopher Nolan, cinema's most expensive case of divine possession. The man spent six months perfecting Interstellar's sound mix with Hans Zimmer — not the score, not the whole soundtrack, just the mix. He is every Greek god's favorite kind of mortal: the one whose hubris manifests as pure, crystalline obsession.

Nothing exists in Nolan's universe without submitting to his exacting specifications. Control, to him, isn't just artistic vision — it's metaphysical imperative. Where other directors might accept the laws of physics, Nolan treats them like a first draft that personally insulted his mother. I won't even start speculating about his morning toast routine. Some psychological wounds are better left unopened.

Homer’s pantheon would approve the Nolan-esque, of course. The gods orchestrate reality through sound itself, and I'm not being metaphorical here. In the poem, the Sirens offer Odysseus a seductive trade: abandon your journey home to hear the glorious tales of Troy, the same battles that made up the Iliad. Their verses deliberately mirror particular Iliadic formulas, weaving the language of war and conquest into their melody.

When they invite Odysseus to their island, they're inviting him to desert not just his ship but the entire poem he inhabits; to transform from the cunning survivor of the Odyssey back into a traditional warrior-hero of the Iliad.

For Nolan, whose layered sound design in films like Inception used audio cues to signal shifts between dream levels (the infamous dream stacking!), the epic's auditory architecture is bound to have him HYPED UP. I can already see him hunched in a hermetically sealed sound booth in London, surrounded by enough processing power to launch several Mars missions, asking increasingly metaphysical questions into the void:

How do I capture divine speech that flickers between mortal disguise and immortal revelation?

Surely I can’t just add reverb and call it “god voice”?

What frequencies should I play with to make Athena speak simultaneously as both goddess and a mentor?

How do I create a soundscape where the sound of poetry and prophecy interweave?

It can't be just obvious distortion but a subtle manipulation of rhythm, meter…and even resonance?

Should I just TENET this and go full-on temporal?

I know what you’re thinking. Shit dude, this is next-level quantum superposition in audio form. Confirmed, my dear Nolanphile. It absolutely is. And if there’s a maniac out there who can attempt to pull this off with a straight face, it is Sir Christopher Nolan.

*no such calculator exists but if you want a deep dive on Nolan plot twists, upgrade your subscription, message me and I shall deliver.

filming the gods (a technical proposal)

This divine quantum mechanics extends throughout the epic. When the gods intervene, they operate through what the text calls ἐπιφάνεια — manifestation that is simultaneously revelation and concealment. Zeus's will expresses itself through weather, bird signs, and human actions, all carrying different levels of divine transparency. Poseidon's anger becomes indistinguishable from the sea itself (Cue Nolan nodding in fervent agreement). The gods are, in effect, additional dimensions of reality that mortals glimpse only in fragments.

So here's where Nolan's adaptation faces its Charybdis: How do you film quantum superposition? Hollywood has trained us to expect divine intervention as either obvious special effects (lightning bolts, glowing figures) or purely psychological metaphor (“Maybe the gods were inside Odysseus’s head all along!”). But Odyssey will require something far more sophisticated. When Odysseus speaks to Athena, the conversation happens on at least three levels simultaneously: practical discussion of tactics, psychological exploration of wisdom, and genuine divine communion. All are equally real, equally present. And I’m not even joking.

The epic's divine machinery isn't decorative — it's deeply structural. Following might be Nolan's origin story of mindfuckery, but not in the way you'd expect. Working with $6,000 and borrowed 16mm film, he couldn't rely on fancy tricks to show his protagonist's descent into criminal obsession. Instead, he turned limitation into methodology. Actors rehearsing each scene like theater, every take precious because film stock was too expensive to waste. "You take it away and show them what they had," his burglar Cobb declares—a philosophy of revelation through removal that feels weirdly perfect for depicting divine intervention.

It sure must be nice, of course, to graduate from borrowed 16mm film to IMAX cameras, but Nolan's obsession with making the impossible feel tangible hasn't changed since those Following days. His documented preference for in-camera effects and practical illusions (e.g. the rotating hotel corridor in Inception, Interstellar's tesseract built as a physical set) springs from an understanding that reality straining to represent the impossible creates its own kind of magic.

Odyssey demands exactly this type of tactile wonder. How can we watch Athena transform Odysseus — making him taller, broader, his hair flowing like hyacinth — if it looks like a standard CGI wipe? No. Her divine touch must feel more real than real, a trick of the light that's subtle enough to make us question reality itself.

The brand new IMAX technology, the big budgets and the even bigger obsessions might actually serve the text in that sense. So yes, to go on the record here, Nolan can tinker obsessively with wave sounds for two entire lunar cycles if it means he gets this one right.

time is a flat circle (and nolan's about to prove it)

Try explaining Odyssey's timeline to someone who's never read it. Watch their face transform from polite interest to existential bewilderment as you detail how Homer casually dropkicks linear narrative into the Aegean. Our poet launches his epic with a divine coffee klatch on Mount Olympus, then pirouettes backward and forward through a decade of adventures that may or may not have happened the way our unreliable narrator claims they did. If your listener's still following by the time you get to Odysseus telling stories about himself in the third person like some Bronze Age Instagram caption, buy them a drink. They’ve earned it.

Now imagine pitching this structural chaos to a major studio in 2024. "It's a three-hour epic where time isn't just non-linear!! It's actively hostile to the concept of linearity itself!!!". The studio executives would need smelling salts. Lucky for us, Nolan's built his entire career on making audiences question whether time flows like water or crystalizes like ice.

Professor Christos Tsangalis argues that Homer's real revolution wasn't just jumbling up his story's chronology for kicks. The poet invented an entirely new framework for humans to process existence through narrative. Before Odyssey, tales of warriors returning from war played out like ancient Greek road trip movies — get from point A to point B, maybe battle a monster or two, roll credits. But Homer gazed at that format and thought: "adorable, but what if we made it about the existential vertigo of trying to return to a self that might not exist anymore?"

When Odysseus recounts his wanderings to the Phaeacians, we're witnessing Western literature's first great unreliable narrator in action. He sits at their feast spinning tales about himself that might be lies but contain deeper truths than mere facts ever could. Nolan's protagonists would feel right at home in this metaphysical maze. His characters exist in perpetual states of psychological flux, trying to crystallize fluid memory into something stable even as the act of remembering transforms the memories themselves.

Nolan's fascination with consciousness experiencing time as psychological construct rather than linear progression runs through his entire body of work. The Prestige's dueling magicians sacrifice their present selves to past fixations. Memento's Leonard Shelby, unable to form new memories, exists in an eternal now haunted by an unfixable past. Cobb in Inception can't trust his own perception of duration any more than Odysseus can rely on his grip on reality. They're all trapped in labyrinths of their own making, where past and present dance like particles in quantum superposition.

"Time is the most cinematic of subjects," Nolan says in an NPR interview, "because before the movie camera came along, human beings had no way of seeing time backwards, slowed down, sped up." Nolan is correct here. “People have no organ to perceive real time.” Pascal Wallisch, Clinical Associate Professor of Psychology at NYU, says. “The passage of time has to be inferred from other things, and this is highly malleable. So a filmmaker has tremendous degrees of freedom to play with that presumption.”

Perhaps this explains why Christopher Nolan seems like such an eerily good match for this material. Where other directors treat time as mere foundation for their narratives, Nolan transforms it into an active psychological force. In Dunkirk, he used the compression of time to create claustrophobia despite vast open beaches. In Insomnia, endless daylight becomes a weapon that works against human nature itself.

Odyssey offers him the ultimate canvas for this approach, a story where time isn't just bent but actively hostile to linear experience. It gives Nolan the chance to push even further into that unstable territory between memory, identity, and time, where psychological and temporal displacement become indistinguishable.

What I love about his NPR interview is the moment he lets the mask slip. "As I get older," he admits, "as my kids get older, your sense of time changes — that feeling of losing things and things slipping away and things moving ahead without us."

Strip away the theoretical physics and multidimensional metaphysics, and you'll find Nolan's just been making increasingly elaborate therapy sessions about his fear of time all along. And with The Odyssey, I desperately want him to take everything he's learned about warping reality and unleash it on Homer's cosmic scrambling of chronology.

Though maybe this time around, Christopher, let's make sure we can actually hear what the gods are saying over Hans Zimmer's existential bass drops.

rewriting the women who wait

Look, I love Christopher Nolan's work with the fervor of someone who spent her teenage years explaining Memento's timeline to increasingly frustrated friends. I really really do. But loving something means being honest about its flaws, and my god, does this particular genius have his blind spots. My fellow Nolan devotees: breathe deeply, perhaps pour yourself something strong, and read this next part with curiosity - not straight-up judgment. Let’s do this.

Nolan's cinematic tryst with the fairer sex has, shall we say, a certain reputation. The man who likes to bend time like intricate origami somehow is known to portray women in his universe as a beautiful equation meant to make men sad about architecture. Mal haunts the Inception dreamscape like a virus in the system, her entire existence compressed into an infection in Cobb's subconscious. Dr. Brand in Interstellar solves quantum gravity between coffee breaks but spends her screen time mooning over Edmund's frozen corpse in space (girl, I promise there are other fish in the sea...or at least other scientists in the multiverse). Even Miranda Tate gets the dubious honor of dying TWICE in The Dark Knight Rises — once as Bruce Wayne's lover and again as Talia al Ghul, her character arc collapsing into a black hole of daddy issues.

These women orbit Nolan's protagonists with the predictability of celestial bodies, their gravitational pull measured only by how thoroughly they can traumatize the male psyche. In Nolan's universe, emotional complexity often comes with a Y chromosome requirement.

The cast list for The Odyssey reads like the group chat of my DREAMS — Lupita Nyong'o, Charlize Theron, Zendaya, and Anne Hathaway stacking talent upon talent (manifesting a scene where Theron throat-punches a cyclops with that Atomic Blonde skillset). On paper, these powerhouses could transform Homer's divine women into the cosmic forces they truly are...except the cast alone doesn’t soothe my present anxieties.

With The Odyssey, Nolan faces something belonging to an entirely different constellation. Ancient Greek scholars branded it πολυγύναιος — "woman-rich" — a text so dense with female complexity it makes the Iliad look like a CrossFit bros group chat. These women inhabit interior worlds as vast as Odysseus's ocean, each one orchestrating her own symphony of power moves beneath society's surface. Their dreams spiral beyond the boundaries of bronze-age patriarchy. Their schemes rewrite the rules of divine and mortal authority.

In the epic, while our protagonist gets to galavant around the ancient world having divine hookups with beautiful goddesses (the OG James Bond, if you will), Penelope is stuck in Ithaca fending off 108 entitled suitors who want to wife her up and steal her kingdom. To bring this back to today’s culture, think of the most insufferable men you've ever encountered on dating apps, multiply that energy by a hundred, add some Bronze Age entitlement and a literal kingdom as the prize. That's Penelope's daily reality. But my girl weaponizes the domestic sphere like a chess master. Penelope's loom becomes her war room. The suitors admire her dedication to grief while she orchestrates their annihilation through seemingly dutiful needlework.

The power dynamics at play are crucial here. The disparities, the double standards, the sheer audacity of it all, aren't subtle. Where Odysseus gets freedom of movement and action, sailing seas, battling monsters, bedding goddesses, Penelope must work within suffocating constraints. Penelope's famous weaving becomes more than clever subterfuge — it's an entirely different manifestation of power than her husband's brute force solutions. Her work is one of calculated undoing, of creating something whose only purpose is to be unmade.

Her violence destroys nothing. His, in contrast, destroys everything.

My teacher loved comparing Penelope's intellect to Odysseus's strategic brilliance, a compliment that revealed more about academia's limitations than her actual complexity. How perfectly academic, measuring female intelligence only by its proximity to male benchmarks. Nonetheless, as the genius playwright Brian Friel claims, every translation is an interpretation, and every interpretation is a reflection of its time. Odyssey keeps transforming precisely because we keep bringing our own blind spots to its pages.

My biggest issue with Tenet has always been about Kat Barton. In theory, she's a towering presence (Debicki is literally 6'3"), an art appraiser with enough savvy to navigate international art fraud. In practice, she becomes another woman whose primary narrative function is to be abused, rescued, and defined entirely through motherhood.

I imagine Circe watching from her island palace, mixing a potion of particularly refined spite. Homer's divine women transcend these simplistic boxes by design. When she transforms men into swine, she's conducting a philosophical inquiry into human nature itself. Calypso, in turn, forces Odysseus to confront the ultimate choice between divine perfection and messy mortality. These women don’t “drive” the plot. They're existential challenges that rewrite the rules of the plot itself.

The text's brutality toward women also requires our unflinching attention. When Odysseus returns and orders death for the slave women who slept with (or were raped by) the suitors — "Hack at them with long swords, eradicate all life from them" — we see how violence against women operates across class lines. This isn't background color or period detail. It’s central to understanding how power flows through this world. The "idealized" society takes this violence for granted, but it also depends on it.

Even the mortal women refuse to follow convenient narrative paths. Nausicaa encounters a shipwrecked stranger radiating divine energy, a setup practically begging for the standard princess-meets-hero romance. But instead, she navigates the situation with political precision that would impress Lady Macbeth herself. The Greek word for her response, θάμβος, captures something far beyond simple attraction. It's the vertigo of recognizing divine possibility in human form, the moment mortality brushes against something infinite.

Any modern adaptation would likely reduce this to romantic subplot fodder but Homer gives us a masterclass in female agency that needs no male validation to justify its existence.

And then there's the pièce de résistance, the beating heart of this adaptation. Nolan's entire career has been building towards this. A story about time! Memory! Shifting planes of reality! Are you kidding me! But the women of Odyssey have been playing these games since before Rome was a twinkle in Romulus' eye. They weave and unweave time itself, transform bodies and souls, challenge every boundary between the divine and the mortal. Boundaries, blurred. Realities, bent. Time itself, subject to their craft.

To honor the spirit of this woman-rich epic, Nolan must confront its horrific truths without narrative submission. People marginalized by the Western canon have long approached these texts both as endorsements of their authors' values and as evidence of how awful those values could be.

I do not want to see neither a sanitized “feminist” revision (please no Barbie in Ithaca) nor plain period-accurate barbarity.

I want to see an adaptation that exposes the full moral complexity of its world. Acknowledging both the distance between their time and ours, and the disturbing similarities that persist.

re-mystifying the poem, not preserving it

We Greeks can be weirdly protective of our cultural exports, especially the ones that helped shape Western civilization. It's the equivalent of watching your brilliant child get repeatedly miscast in school plays. You know they're capable of Shakespeare, but someone keeps putting them in productions of High School Musical. Our first instincts? Panic, pride, and a whole lot of protective side-eye with a side of freddo.

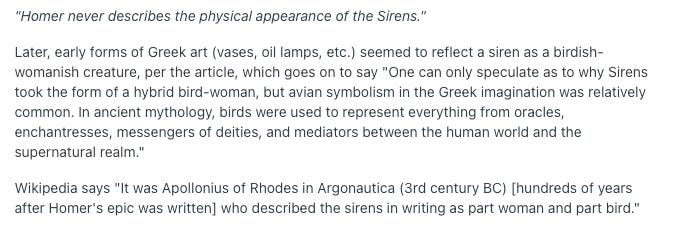

Beyond that bubble, Odyssey stirs a different kind of conversation. I used to think the biggest zeitgeist-y hullabaloo around the poem was: “Is it too patriarchal? Too ancient? Too revered to touch?”— the usual cocktail of highbrow fretting. Then I discovered a separate corner of the galaxy where Odyssey might as well not exist. Call it the black hole of “I literally never heard of Homer until YouTube told me Nolan was directing something.” And that, weirdly enough, rattled me more than any ban or boycott ever did.

captures this tension of cultural decay in her reporting on the response to Nolan's adaptation announcement: 23-year-old influencer Matt Ramos broadcasting his Homer revelation to 12.8 million viewers, each reply more gleeful than the last about their own artistic blind spots. The shame flows backward now, targeting anyone who dares suggest these gaps might matter. Welcome to 2025, where knowing things makes you the asshole.The Parthenon restoration project in Athens mirrors our fraught relationship with ancient texts. Tourists arrive expecting crystalline wisdom carved in marble, find instead a perpetual construction site. The scaffolding has outlived my childhood, will likely outlive me. Yet we persist in trying to rebuild something that was never whole, as if enough meticulous engineering could strip away history's accumulated grime. Hollywood approaches Greek tales with similar hubristic optimism. Just need to make it more "accessible," more “smooth” around its jagged edges and into something more “palatable” for modern sensibilities.

But Odyssey bleeds. After slaughtering the suitors, Odysseus forces their women to scrub the gore from his halls before he hangs them, their feet "twitching but not for very long." His coastal raids treat women as spoils of war, property to be claimed alongside cattle and gold. The text makes us watch every horror. Slavery, divine cruelty, sexual violence against women, men slicing each other open for sport. When Odysseus captures Polyphemus's island, his men gorge themselves on wine and meat while enslaved women wail in the background. The poem doesn't look away.

This brutality matters beyond mere shock value. Umunc's work on generic hybridity illuminates why: real narrative power emerges from letting contradictions crash together. Shakespeare grasped this centuries later, interweaving aristocratic drama with ribald comedy, metaphysical inquiry with vulgar spectacle. Odyssey charted this territory first. Its protagonist oscillates between tactical virtuosity and ruinous vanity. After the famous "Nobody" wordplay blinds the Cyclops, Odysseus can't resist screaming his real name across the waves, earning a curse that drowns most of his crew. Glory and idiocy arrive in the same breath.

These aberrations form the text's essential architecture. As Chartier argues in Cultural History: Between Practices and Representations, such patterns carry "historically transmitted meanings" that resist modernization. Penelope's nightly unraveling of her weaving undermines the very foundation of masculine authority. Her domestic craft weaponizes a funeral shroud into an instrument of political resistance. The gods embody this duality too, debating fate while behaving like a dysfunctional family on a reality show. Mount Olympus meets Real Housewives, except when someone gets voted off the island they actually die.

Modern adaptation demands more than surface renovation. It requires re-mystification. Odyssey's potency dwells in its refusal to resolve its own contradictions, its insistence that violence and wisdom, glory and ignominy spring from identical soil. Nolan's version must embrace this fundamental disorder. No traditional hero's journey, no facile moral victory. A faithful adaptation won’t paper over these realities with IMAX spectacle or high-flown dialogue. It’ll have to shove them in our faces, forcing us to confront exactly how messy the foundations of “Western civilization” can be.

We’ve come to inhabit, as

writes in her brilliant recent piece, a culture where ”ignorance has become an accepted trait, being learned a social faux pas”. Odyssey offers an antidote. Not because it's ancient or canonical, but because it isn’t interested in playing it safe. It shows us a world where triumph comes tainted with atrocity, where even the gods can't keep their stories straight.Do modern audiences actually deserve that complexity?

Do we even want it?

If this is the culture we’re heading towards, maybe we’ve lost the appetite for a story that won’t just sit there and behave.

What makes me hopeful is that Odyssey continues to rattle the foundation of every new age that stumbles upon it—ours included. Ancient Athenians found in it a sophisticated exploration of divine law versus human agency (particularly with the hacking the Greek language itself parts). Medieval Christians discovered an allegory about the soul's journey (though they conveniently glossed over all that polytheistic sex). The modernists, bless their anxious hearts, unearthed enough psychological complexity to keep Freud's couch busy for centuries.

So maybe we don’t deserve this complexity, that’s true, but we need it all the same.

finding my way back to the text

Memory plays tricks in Mediterranean light. I remember the weight of my school copy of Odyssey, its pages dog-eared and annotated in teenage scrawl. I remember sunlight streaming through classroom windows while my teacher's voice wove stories of homecoming and transformation, of mortals and gods playing their eternal games of fate and chance.

I remember thinking: this is mine. This story belongs to me, to my language, to the very stones of Athens that I walked past every day.

Now Hollywood comes calling for Homer again. Another adaptation, another journey across those ancient seas. Part of me wants to guard this text like Athena watching over her favorite hero. Fiercely, jealously, with godly determination. The same part that bristles every time someone mangles the pronunciation of "Odysseus" or reduces Penelope's political genius to wifely devotion.

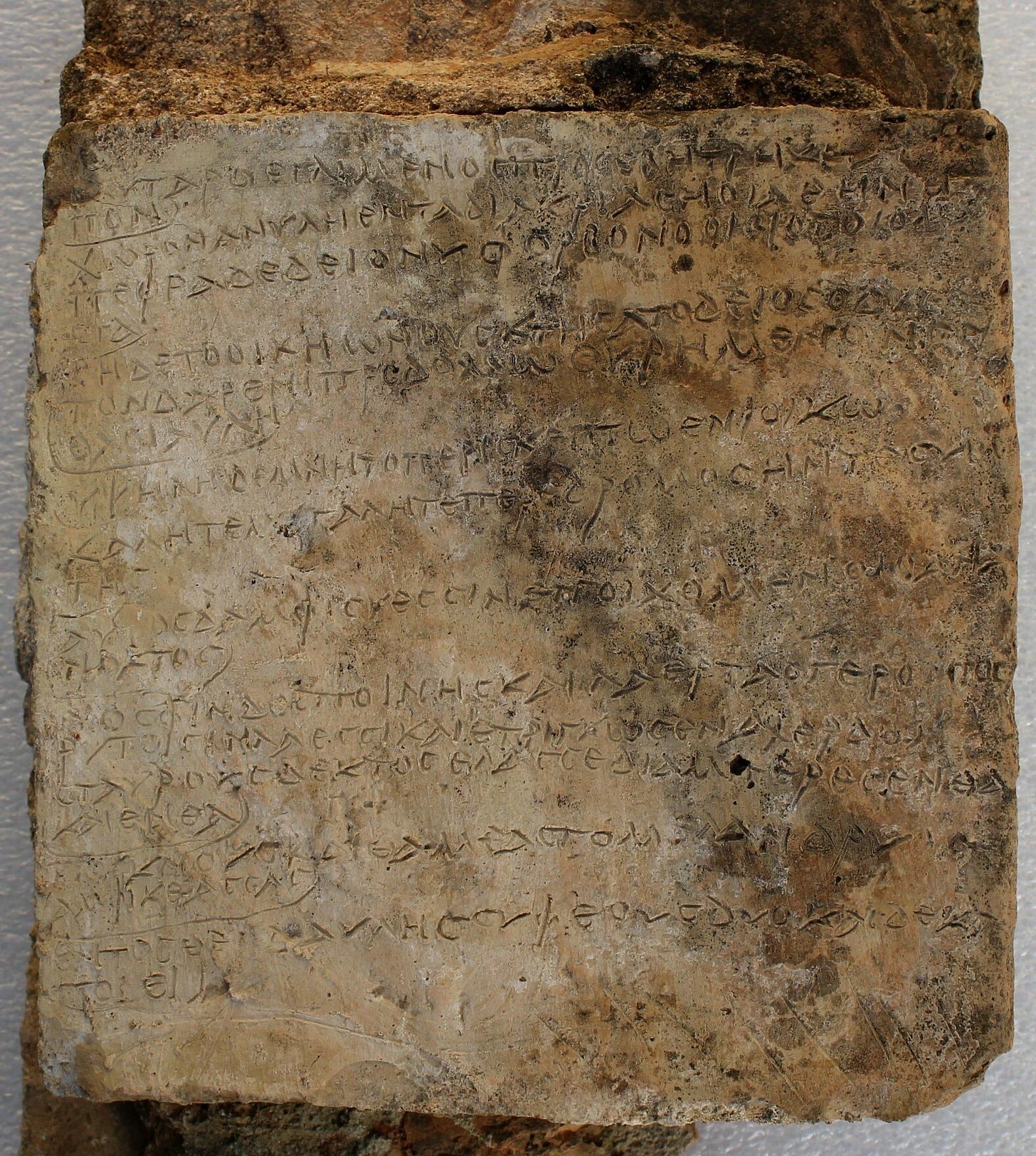

But stories, like heroes, must wander. They must face transformation, encounter strange new shores, risk being changed by the very journey they undertake. When Penelope finally recognizes her long-lost husband, Homer captures this eternal dance between preservation and change in words that still quicken the pulse:

‘οὕτω τοι τόδε σῆμα πιφαύσκομαι· οὐδέ τι οἶδα,

ἤ μοι ἔτ᾽ ἔμπεδόν ἐστι, γύναι, λέχος, ἦέ τις ἤδη

ἀνδρῶν ἄλλοσε θῆκε, ταμὼν ὕπο πυθμέν᾽ ἐλαίης.’

ὣς φάτο, τῆς δ᾽ αὐτοῦ λύτο γούνατα καὶ φίλον ἦτορ,

σήματ᾽ ἀναγνούσῃ τά οἱ ἔμπεδα πέφραδ᾽ Ὀδυσσεύς·

R. F. Kuang's Babel has famously said, "an act of translation is always an act of betrayal", and I couldn’t agree more. But this translation from Emily Wilson speaks most authentic to me:

Now I have told the secret trick, the token.

But woman, wife, I do not know if someone—

a man—has cut the olive trunk and moved

my bed, or if it is still safe.”

At that,

her heart and body suddenly relaxed.

She recognized the tokens he had shown her.

Perhaps what I really want from Nolan isn't perfect preservation but fearless exploration. Not another careful museum piece that treats Homer's epic like some fragile ancient vase, but what every woman who has read the Odyssey has yearned for: the courage to name that outré ache that Wilson called "intimate alienation". That sensation of being both deeply connected to and fundamentally distanced from this masculine text.

I want him to show us Penelope's hands, thick and muscled from her endless labor at the loom, while her husband's adventures earn him immortal fame. I want him to name the violence plainly. Not just the glorious spearing of suitors, but the hanging of the slave women, strung up like birds in a snare, their feet twitching in the air. To make visible what centuries of translators buried beneath heroic platitudes.

Because Odyssey isn't just a Greek story anymore. And I have to accept that.

It belongs to everyone who has ever been lost, everyone who has ever struggled to find their way home only to discover that home itself has changed in their absence. It belongs to every woman who has had to weave and unweave her own fate, every child who has searched for an absent parent in the face of strangers, every wanderer who has chosen painful mortality over comfortable oblivion. It belongs as much to the silenced as to the singers. It belongs to everyone who has ever recognized themselves in its brutal revelations about power and gets to tell their story of home.

When I walk through Athens now, past tourists snapping photos of ancient stones, I sometimes catch echoes of Homer's verses in the evening air. They mingle with car horns and coffee shop chatter, with children's laughter and old women's gossip, with all the sounds of a city that has survived its own endless transformations and occupations.

These days, those verses feel like a knife twist in my gut. Wilson understood this visceral discomfort when she became the first woman to translate the poem into English. Where others saw heroic glory, she exposed the raw machinery of power grinding beneath. Where others wrote of "maids" and "servants," she wrote "slaves”. Where others reached for grand, archaic language to elevate the text — "Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns" — Wilson stripped it bare: "Tell me about a complicated man." She knew that ornate language was just another way to "silence dissent," to make power seem natural and exploitation inevitable.

So yes, I will watch Nolan's adaptation with my heart in my throat, hope and fear wrestling like Proteus shifting shapes. I will wince at every modified plotline, smile at every captured nuance, argue passionately about creative choices with friends who know the text by heart. I will most certainly cry my eyes out with pride.

But mostly, I want to feel that same vertigo I felt when I first realized that everything I thought I was protecting — the poetry, the tradition, the sacred memory of it all — was just another way of keeping others out.

P.S. If anyone from Sir Christopher Nolan’s team wants to talk, my DMs are open.

A final note for people with taste 🫦

While the internet's prioritizing hot takes and SEO-optimized nothingness, I’m trying to building something genuine with this newsletter: a sanctuary for people who believe film and tv criticism can be thoughtful, accessible and fun all at once.

For the price of a truly mediocre sandwich, consider joining the resistance with a paid subscription – it keeps independent film writing alive and the algorithms at bay.

Plus, you'll get exclusive access to After Credits, my monthly watchlist of films & tv shows that will make your brain do the happy chemicals AND save you from doom-scrolling.

Now go forth and raise those standards, darling.

- Sophie x

You’ll see I purposefully use ‘Odyssey’ (the poem) and ‘The Odyssey’ (Nolan’s adaptation). The poem in its original form does not have a ‘the’ but Universal seems to use it.

Homer’s identity is a hugely debated topic. Some scholars claim he is solely responsible, others claim he doesn’t exist in the first place while some anthropological evidence suggests a woman could be behind it all. For the purpose of the essay, I’m making some significant simplifications but this is a remark worth noting.

I hope Nolans odyssey will be more like Eggers Northman than Gladiator II. In his previous films Nolan showed that he cared about physics(Interstellar black hole is the most accurate). I hope he cares also about history and mythology. I think the costumes will look authentic and his insistence on practical effects will create something that will look good.

I also had a long, long Troy phase. Someone needs to form a support group for people like us...

I really liked this. Parsing your Greek took me right back to learning it at school, and made me desperate to go back to Athens. Did you ever read Pat Barker's books? The Silence of the Girls is really more about the Iliad, but in the context of a consideration of all the different recent interpretations of Homer I'd guess it's one of the most popular (though, yeah, not a film). And my guess is that it could be a good example of what you said you don't want: a modern-day feminist retelling of a Bronze Age story (see also: Madeline Miller and all her imitators).