david lynch made his own furniture

An emergency tribute to the artist, to the extraordinary human.

There's something unexpectedly tender about watching David Lynch report the weather. Not the surreal nightmares he crafted for the screen, but simple YouTube videos: an older man at his desk, telling us about his morning. No hidden meanings. No red curtains. Just a ritual that made me feel less alone during those endless pandemic mornings, when time seemed to blur and the world felt unreal.

I've always found myself drawn more to Lynch as an artist than his cinema alone - the raw darkness of his films speaking to truths I understand but don't always want to live inside. What moved me more deeply was watching him devote himself to craft in all its forms. How to move through the world as an artist, as a human being. Beyond the darkness of his films lived someone whose creative spirit poured into every aspect of life with surprising tenderness.

David made lovely furniture - not as a hobby or an artistic statement, but as a fundamental practice of being. In his workshop, where sawdust caught light like microscopic stars, this mythical director would spend hours with wood and tools, studying grain patterns as if they were secret maps, perfecting joints with the same obsessive precision he brought to his films. These weren't art pieces meant to shock or provoke, though they held their own strange beauty. They were tables and chairs, things meant to hold us, to last, to be useful. A Lynch table meant for Sunday dinners, for coffee cups and elbows, for the weight of ordinary lives being lived.

The comic strip he drew for years, "The Angriest Dog in the World," was perhaps his strangest meditation on stillness. The dog was so angry it couldn't move, trapped in a yard by the sheer weight of its rage, frozen in the same taut position frame after frame, day after day, for a decade. Only the words above changed, floating like disconnected thoughts over the unchanging scene. Here was a man known for his moving images choosing absolute stillness, finding meaning in what refuses to change. The dog became a koan. Was it truly angry, or merely stuck in the performance of anger? Was its stillness a prison or a form of transcendence? Lynch never explained, just kept drawing the same four panels, the same rigid dog, letting the mystery deepen with each passing year.

His dedication to transcendental meditation began in 1973, when he found himself crying in his first session, not from sadness but from recognition. For the next fifty years, he'd speak about this practice with a kind of raw wonder that made cynicism impossible. The mystery wasn't in his films or his art, he insisted. The mystery was in the silence between thoughts, in the simple act of showing up each day to face whatever rises.

Inside every human being is an ocean of pure, vibrant consciousness. When you “transcend” in Transcendental Meditation, you dive down into that ocean of pure consciousness. You splash into it. And it’s bliss. You can vibrate with this bliss. Experiencing pure consciousness enlivens it, expands it. It starts to unfold and grow. If you have a golf-ball-sized consciousness, when you read a book, you’ll have a golf-ball-sized understanding; when you look out a window, a golf-ball-sized awareness; when you wake up in the morning, a golf-ball-sized wakefulness; and as you go about your day, a golf-ball-sized inner happiness.

― David Lynch, Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity: 10th Anniversary Edition

We often reduce artists to their most provocative works. We remember the severed ear in Blue Velvet, the mystery of Mulholland Drive, the nightmare of Eraserhead. But Lynch spent his days building things to sit on, reporting the temperature, drawing the same dog, sitting in silence.

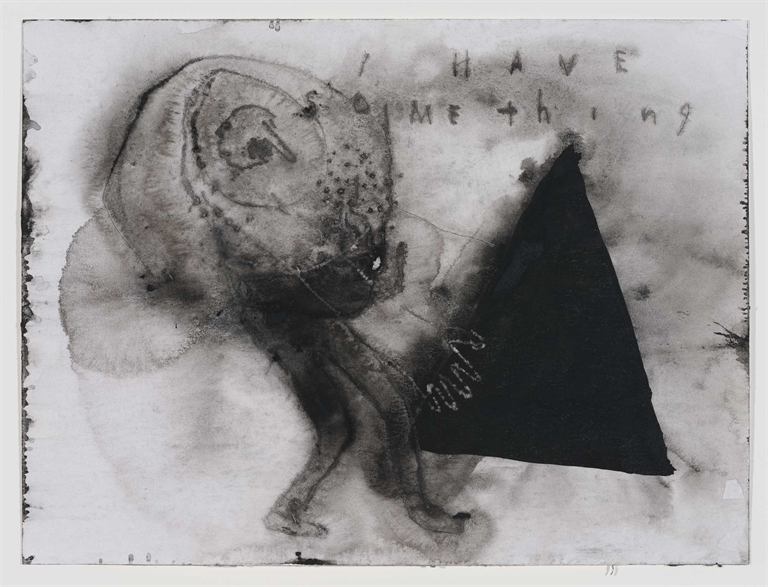

He painted constantly, an act of excavation rather than creation, thick planes of matter that seemed to have their own gravitational pull. In his studio photos, you can see how he'd build these surfaces up over months, each layer adding density until the canvas became almost geological. Unlike his films, which he'd discuss for hours, he rarely spoke about these works. They existed in a different register of his imagination, one that didn't need or want translation.

The boundaries between his arts were porous, everything bled into everything else. One piece shows a figure drowning in black paint that seems to pulse with its own heartbeat. Yet the same hands that created these fever dreams spent hours sanding chair legs until the wood was 'happy.' He opened a nightclub in Paris and obsessed over every detail. Not for art's sake, but because details matter.

What do we make of someone who could hold such extremes? Who could birth our most sadistic dreams on screen while spending his mornings telling us about the sunshine? Who could revolutionize cinema while caring deeply about the grain pattern in a chair leg?

Perhaps that's what makes his loss feel so profound. We didn't just lose a legendary filmmaker. We lost someone who showed us that creativity isn't just about the masterpieces. It's about how you pour your coffee in the morning. How you sand wood until it's smooth. How you look at the sky each day and think someone might want to know what you see. In a world increasingly engineered for maximum impact, Lynch chose to also live in life's quietest moments. To make things with his hands. To sit in silence. To report the weather.

He contained multitudes, yes. But more importantly, he showed us that maybe we all do. That the same hands that create nightmares can also build tables where people will share meals for generations. That the same mind that sees darkness can also delight in telling strangers about a sunny day.

The furniture remains. The weather reports are archived. The comic strip still makes no sense. ‘Club Silencio’ still plays his music. And somewhere, the tools in his workshop are quiet now, waiting for hands that will never return to make something beautiful and useful and strange.

"Sometimes a wind blows," Julee Cruise’s angelic voice guided us through David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, "and you and I float in love and kiss forever”. When scoring the film in 1986, he became haunted by This Mortal Coil's version of "Song to the Siren," but the licensing fees remained out of reach. Instead of compromising, he and Angelo Badalamenti began crafting something entirely new. A piece that would capture that same oceanic blend of bliss and oblivion. They needed a voice that could carry both innocence and knowing, heaven and earth. In Julee Cruise, they found something more. The resulting album was Lynch's agonies and hopes translated into sound, another bridge he built between darkness and light.

Like his furniture, like his morning weather reports, it was a thing made with care, meant to hold us, to last, to guide us through the shadows he kept mapping.

Sometimes a wind blows

And you and I

Float

In love

And kiss

Forever

In a darkness

And the mysteries

Of loveCome clear

And dance

In light

In you

In me

And show

That we

Are loveSometimes a wind blows

And the mysteries of love

Come clear.From “Mysteries of Love”

He carried others' pain with a fierce and steady compassion that feels almost extinct now. When survivors of abuse wrote to him after Fire Walk With Me, devastated that he somehow knew their private wounds, he gave them the dignity of being seen. In 1990, through FBI Agent Denise Bryson, he showed trans viewers a future where they could be respected, powerful, whole. "When you became Denise," he told her decades later in The Return, "I told all of your colleagues, those clown comics, to fix their hearts or die." The line pierces through time - both a protection and a promise.

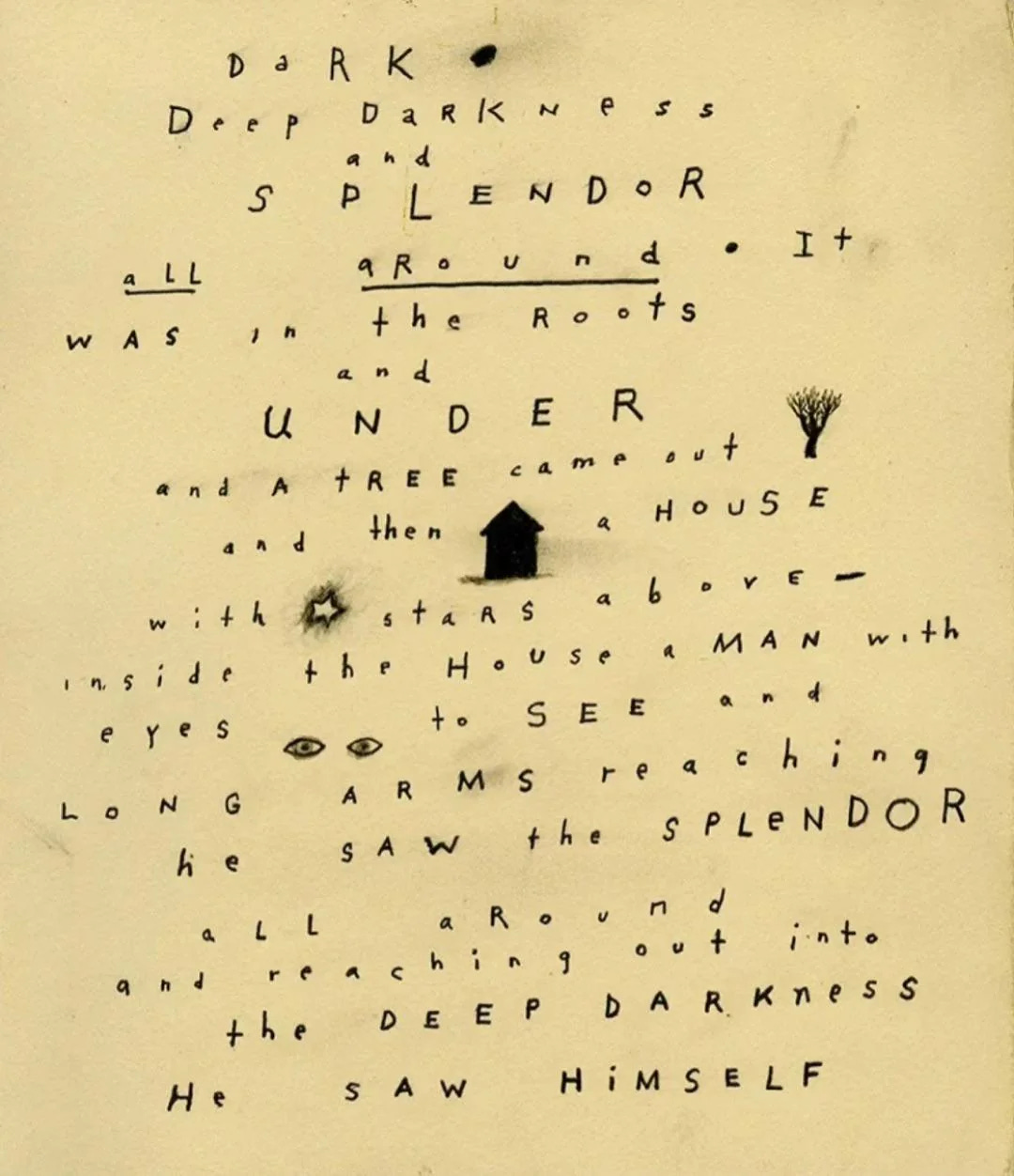

He wrote about darkness too, “dark deep darkness” and splendor all around it. He found both in his morning rituals - in meditation cushions worn smooth by decades of sitting, in the quiet acts of building things meant to hold us, in looking up each day to tell us about the light breaking through clouds. Even as his hair whitened and his hands aged, he kept walking toward brightness.

The final weather report feels impossible to watch now. The same desk, the same window, the same gentle observation of light and shadow. He taught us that negativity was like bleakness - you turn on a light and darkness goes. But he knew too that we needed both. The mysteries come clear, he wrote, and dance in light. In you. In me.

This is how time passes. Not in the dreams he gave us on screen, but in morning light catching wood shavings. In weather reports about golden sunshine. In meditation cushions holding the shape of absence. In furniture built to outlast its maker.

The last unfinished chair in his workshop will never know his hands. The tools will be passed to someone else. But somewhere, a family is eating dinner at a table he built, their plates resting on joints he carved with patience and care. They might not know his name. They might never see his films. But their lives are held by something he made in those quiet moments between dreams and dawn, between the mysteries of love coming clear.

“Negativity is like darkness. You turn on the light, and darkness goes. We're like light bulbs. If bliss starts growing inside you, it's like a light. You enjoy that light inside and if you ramp it up brighter and brighter you enjoy more and more of it and that light will extend out farther and farther. Maybe enlightenment is far away. But it's said that when you walk toward the light with every step, things get brighter. Every day, for me, gets better and better and I believe that enlivening unity in the world will bring peace on Earth. So I say, peace to all of you.”

― David Lynch, excerpt from Curtains Up

David believed that if you walked toward the light with every step, things got brighter. This morning, a day after his passing, I found myself looking up at the London sky, searching for words to describe the quality of radiance, the way clouds moved across the blue. Golden sunshine for a few brief moments, strangely. But the longer I stared, the more the sky began to feel like one of his shots - too perfect, too still, as if something sad and wonderful might tear through at any moment.

Maybe that was Lynch's real gift. Teaching us that even ordinary light can hide extraordinary mysteries. Or maybe I just miss him, miss knowing he was out there somewhere, building his tables, drawing his angry dog, looking up at the same sky and thinking we might want to know what he saw. Rest in peace, David. X

A final note for people with taste 🫦

While the internet's prioritizing hot takes and SEO-optimized nothingness, I’m trying to building something genuine with this newsletter: a sanctuary for people who believe film and television criticism can be thoughtful, accessible and fun all at once.

For the price of a truly mediocre sandwich, consider joining the resistance with a paid subscription – it keeps independent film writing alive and the algorithms at bay.

Plus, you'll get exclusive access to After Credits, my monthly handpicked selection of films & tv shows that will make your brain do the happy chemicals AND save you from doom-scrolling.

Now go forth and raise those standards, darling.

- Sophie x

Wonderful, thanks for writing this

Your tribute beautifully captures Lynch’s extraordinary ability to infuse creativity into life’s quiet moments. I love how you highlighted that “the same hands that create nightmares can also build tables”—a genuine reminder of the profound humanity within his art.