dark arts for democrats 2028

Because someone has to franchise corruption before someone else does (again).

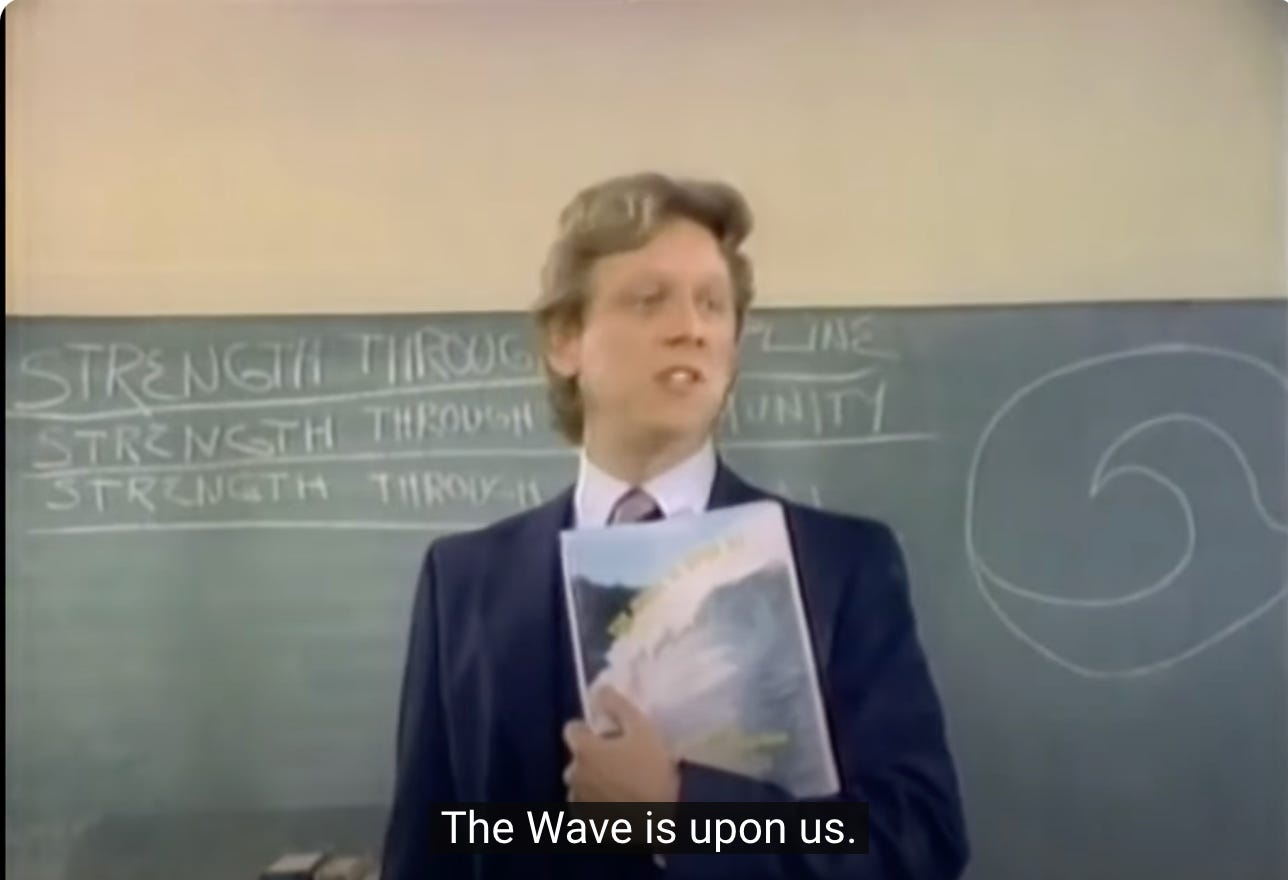

Last night, I watched "A Face in the Crowd" for the fifth time since the election. My apartment's turned into a private cinematheque dedicated to media manipulation and power – the kind that would make Pauline Kael write a 5,000-word essay about American decay through the lens of my coffee cup collection.

For weeks now, I've been processing election results through cinema's most unsettling insights about demagoguery, propaganda, and mass psychology. At first, I told myself this was research: understanding how Trump expanded his coalition across demographics that should have been untouchable to him (like asking why anyone would choose Buddy over Will Ferrell in "Elf," but with devastating real-world consequences), making sense of how a man facing 91 felony charges somehow gained support rather than lost it. Pure academic curiosity, obviously.

But somewhere between "Network" on a Tuesday evening and "The Wave" on a Sunday morning, a more uncomfortable truth emerged. I wasn't watching these films to understand what went wrong. I was watching them to understand what Trump's team got right.

Ezra Klein from the New York Times wrote that the path forward requires curiosity rather than contempt. He's correct, but not in the way he thinks. The real curiosity we need isn't about Trump voters' motivations – it's about why Democrats remain so committed to losing honorably.

Maybe that's why I've been mainlining these specific films (among others) on repeat. Because while everyone else dissects polling data and demographic trends, I keep thinking about how Machiavelli would interpret our current moment through cinema. The man understood something Democrats keep forgetting: power works through stories, not facts. Through narratives that make people choose chaos over order, villains over heroes, comfortable lies over uncomfortable truths.

The four films I've been obsessing over aren't just prescient about our political moment – they're instruction manuals in disguise. Each one reveals a tactical insight so sharp it could cut through the fog of "when they go low, we go high" idealism (a phrase that aged about as well as "actually, maybe Musk will make Twitter better"). The kind of insights that would make Machiavelli say "finally, someone gets it.

Will studying these films' darkest lessons about power make you uncomfortable? Maybe. But discomfort is the point. When a man who attempted to overthrow democracy on January 6th can expand his coalition while openly promising to be a dictator on "day one," maybe Democrats need to get comfortable with being uncomfortable.

What follows is my attempt at a field guide to political storytelling, extracted from cinema's most ruthless lessons about power. Each section breaks down a specific tactical approach that Democrats need to master – because their opponents already have.

Lesson #1: Create the crisis, sell the solution

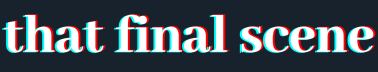

(Or: What "A Face in the Crowd" knew about manufacturing outrage)

A 1957 film accidentally created the perfect playbook for modern political warfare, and America's right wing studied every freaking page without realizing it. While film critics masticate endlessly over Andy Griffith's performance as Lonesome Rhodes, they miss the raw blueprint "A Face in the Crowd" provided for turning anxious citizens into profitable true believers. Through Rhodes' meteoric rise, Kazan and Schulberg mapped out a methodology so effective that modern political operators study it like scripture: identify pre-existing social fractures, amplify them into full-blown crises, then sell solutions that make people feel powerful without threatening the actual power structure. The same blueprint that Rhodes used to build his media empire now shapes our political landscape, where manufactured outrage drives everything from campaign donations to voter suppression efforts.

Rhodes turns garden-variety anxiety into premium cable drama. Every small-town fear - communists under the bed, city folk corrupting our youth, moral decay at the sock hop - becomes a limited series event with matching merchandise. Each crisis arrives with its own QVC collection. Worried about communists? A vitamin supplement makes taking your daily dose feel like joining the resistance. Concerned about urban decay? That official Rhodes-branded jacket transforms you from teenager hanging out to soldier in the war for American values.

He understood something beautiful: people will absolutely buy anything that makes them feel like the main character. Each carefully packaged crisis comes with its own character arc, complete with costume changes and speaking parts. You become the star of your own patriotic crusade, with the merch to prove it. Rhodes created the template that MAGA would turn into a franchise operation. Take any fear, add a logo, and monetize the apocalypse while everyone's busy picking out their costume for it.

Kazan's direction chronicles this evolution through his audience's metamorphosis. Early crowd scenes capture standard American faces - exhausted workers, worried parents, citizens desperate for answers. But by mid-film, these same faces radiate with true believer fervor, requiring their daily dose of manufactured outrage to function. The lighting shifts from documentary-style naturalism to theatrical extremes, turning every Rhodes broadcast into a revival meeting where the congregation performs their assigned roles with increasing zealotry. The camera lingers on faces illuminated by television screens - people who've graduated from spectators to soldiers in an engineered reality.

Today's right-wing media empire runs on pure Rhodes methodology: find a real anxiety (immigration, abortion rights, economic inequality), strip it of context until it fits into perfect story packages, add characters, build tension, deliver catharsis. The left keeps trying to sell complex systemic solutions while the right peddles simple narratives complete with merchandise lines.

The film's most brilliant sequence reveals the endgame. Rhodes runs a summer camp for budding authoritarians - complete with merit badges for crushing democracy. His "Fighters for Freedom" youth program turns parents misty-eyed as their kids transform from TikTok scrollers into uniformed warriors. These kids get starring roles in a story about saving America from threats Rhodes invented over breakfast. It's like getting cast in the school play, but the play comes with a sense of purpose, belonging, and power in a world that feels increasingly chaotic.

This explains so much about 2024. Latino voters, Black men, young women - all choosing to join narratives that should make zero sense for them. But Rhodes understood. Give people a crisis they can actually solve, and they'll pick it over abstract systemic problems every time.

Democrats could absolutely master this playbook. Take real economic inequality and turn it into weekly battles against specific corporate villains. Transform vague concerns about democracy into tangible fights at your local election board. Give everyone a character arc, meaningful action scenes, and victories worth celebrating.

Because that's the beautiful trick these films revealed. Power works through stories that make people feel like main characters. Time to start writing better ones.

Lesson #2: Don't fight rage, monetize it

(Or: How "Network" turned anger into prime time gold)

I'm watching Diana Christensen turn Howard Beale's breakdown into ratings gold, and all I can think about is how Democrats keep losing the rage game. When Beale announces his on-air suicide plan, those executives don't panic - they calculate. Their faces light up with market analysis while discussing how to package mental collapse for prime time. In 2024, this scene burns differently. Every time progressives meet raw voter fury with another policy paper about structural reform, I want to scream. The right has built a rage empire with merchandise, membership tiers, and private jet tours, while Democrats keep trying to fact-check their way out of an emotion fight.

Diana Christensen could very much be the greatest campaign strategist in history. She turned one man's mental breakdown into must-see TV that people consumed like prescription anxiety meds. Faye Dunaway plays her like she's conducting an orchestra of mass hysteria - every focus group testing a different shade of rage, every set piece designed to make Beale's rants feel like religious revival meetings. Even the commercial breaks hit like perfectly timed intermissions in a Broadway show about the end of the world.

Diana's mastery lies in making everyone feel like they belonged in Beale's breakdown. That "I'm mad as hell" moment became their Woodstock - a shared ceremony where screaming out your window at 3am suddenly felt like joining the coolest cult in town. Every person who opened their window, every voice that joined the chorus became part of something bigger than their studio apartment and their microwaved dinner. They graduated from passive viewers into card-carrying members of the Angry As Hell Club, with Diana collecting dues in Nielsen ratings. The power moved through belonging. The rage was just her background music.

The film reaches full power in that boardroom scene where Arthur Jensen converts Beale to corporate cosmology. He stands there preaching the gospel of international finance while studio thunder rolls in the background like God himself just joined the board of directors. Beale, our prophet of anti-corporate rage, transforms into Wall Street's favorite apostle, and his audience absolutely eats it up. Diana built such a perfect temple of outrage that they stayed even when their high priest started worshipping the golden calf.

The congregation showed up every night for their scheduled programming because Diana made the ritual matter more than the message. By the time Beale's ratings dropped, it had nothing to do with selling out - his particular brand of rage just went out of season, like last year's designer handbag collection.

Diana stripped power down to its purest form. She created a megachurch of manufactured outrage so perfect even Machiavelli would slow clap. The studio became her temple, the audience her devoted congregation, every commercial break a perfectly timed "amen." She understood the simple truth: people will absolutely worship anything if you build a beautiful enough temple around it.

Want to build a movement that actually moves? Start with Diana's approach. Create beautiful spaces for communal emotion, give people starring roles in something bigger than themselves, and turn every commercial break into a chance for connection. The blueprint for a better democracy is right there on screen, wrapped in production values so good you almost forget it came from a villain.

Lesson #3: Make them feel chosen

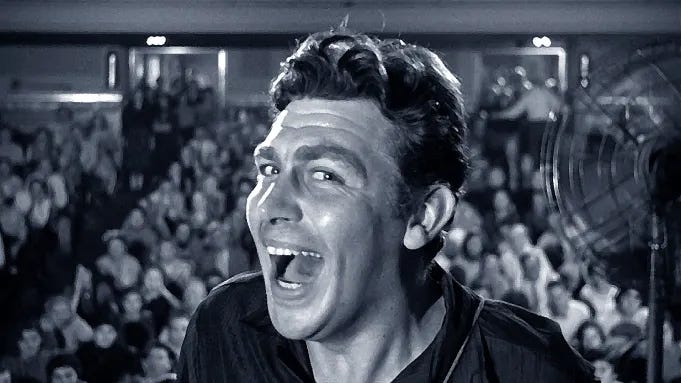

(Or: How "The Wave" turned regular kids into willing fascists)

I keep thinking about that moment in 1981’s TV movie "The Wave"1 where those kids in 1967 California smirk about fascism saying it could never happen here. My history teacher loved screening this film, claiming it would inoculate us against authoritarianism. But sitting right now, rewatching those bored teenagers in their squeaky plastic chairs transform into true believers, I see a masterclass in what Trump understood and Democrats missed. Director Alexander Grasshoff builds his opening with deliberate mundanity - fluorescent lights, linoleum floors, notebook doodles - because the ordinary matters. These aren't special kids. These aren't radicals. These are average American teenagers who become something terrifying through one simple technique. Being made to feel extraordinary.

Ron Jones turned a regular California classroom into the world's most effective dictatorship starter kit. His students went from doodling in their notebooks to becoming the kind of true believers who'd report their own mothers for incorrect salute technique. The special gestures, the membership cards, the rules about how to sit - every detail worked like a perfectly calibrated filter, turning regular teenagers into extras from a very special episode of Triumph of the Will.

The camera tells the whole story. First you get standard classroom shots, all squeaky chairs and fluorescent despair. Then The Wave kicks in and suddenly these kids look like they're filming the season finale of Succession. The lighting hits different - Wave members glowing like they just discovered Facetune, while everyone else fades into that specific shade of irrelevance you only find in high school hallways. Every small adjustment - the way they walk, the coordinated moves, the membership perks - transforms these normal kids into characters in a show about belonging. A show where every episode ends with someone getting upgraded from background extra to series regular, just for saluting the right way at lunch.

The most visceral sequence spans ten minutes tracking The Wave's spread beyond Jones' classroom. These students transform with terrifying precision - the invisible ones strutting through hallways, former outcasts embraced by their new hierarchy, a shy kid becoming an enforcer, a popular girl turning informant against non-members. Each change works like its own short film - hunched shoulders straightening into military posture, casual social butterfly routines hardening into militant precision. Their faces in close-up tell everything. That smug satisfaction of finally being on the inside, of having secret knowledge that marks you as special. MAGA perfected this psychology. Every red hat, every coded phrase like "Let's Go Brandon," every special rally gesture creates layers of insider knowledge, a world where membership means more than just yard signs and brat summer memes.

By day three, The Wave has developed its own economy of social capital. Members create special study groups, reserve cafeteria seats, organize Wave-only parties. Jones barely needs to enforce membership anymore because the students do it themselves, turning exclusion into currency. The film captures this through increasingly claustrophobic framing - hallway shots that once showed teenage chaos now display orchestrated patterns, Wave members moving in coordination while non-members get pushed to the frame's edges.

The experiment worked because students felt ownership over their transformation. Getting in required proving worthiness through action. Learning special phrases. Recruiting others. Enforcing group norms. Every new rule they created, every ritual they developed made them more invested in the system. Trump's base operates the same way - spreading Q drops, sharing conspiracy theory memes with each other, going on each other’s podcasts. They're not just accepting an ideology. They're actively building it. Meanwhile, Democrats keep trying to sell policy positions like they're hawking solar panels at a county fair. They offer voter registration while MAGA offers secret knowledge. They send donation emails while the right creates entire alternative social worlds.

Here's my Machiavellian pitch for the soul of democracy: steal every psychological trick that works. Create local "democracy defense" groups with their own rituals and recognition systems. Replace those sad little "I Voted" stickers with gear that marks specific levels of involvement. Transform donor programs into tiered societies with special access and responsibilities. Build encrypted communication channels for coordinating local action. Create special training programs that graduates have to teach to others. Yes, I'm suggesting we use cult psychology for democracy. Yes, I know how that sounds. No, I don't care anymore. Because watching The Wave after the 2024 election, one thing becomes crystal clear: the only thing worse than using these techniques is letting your opponents be the only ones who do.

Lesson #4: Weaponize the truth

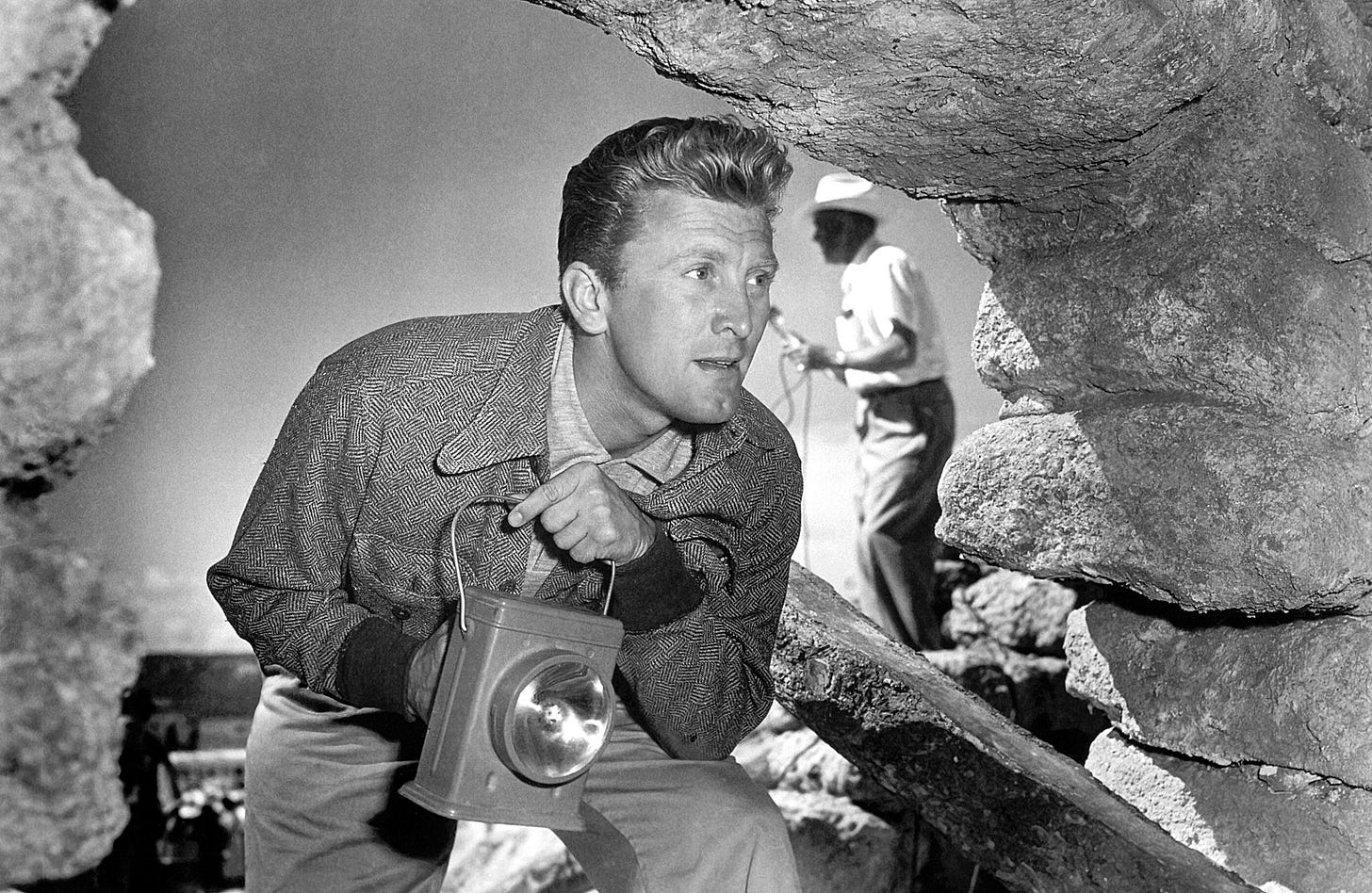

(Or: Why "Ace in the Hole" proves insiders beat fact-checkers)

Here's a thought about conspiracy theories in 2024: people don't believe in QAnon because they're stupid. They believe because it makes them feel smart. "Ace in the Hole" understood this psychology back in 1951, and watching it today feels like reading a playbook for every Trump-era grift.

Billy Wilder builds the film around a simple cave collapse in New Mexico. A man named Leo Minosa gets trapped while hunting for Native American artifacts. The rescue should take hours. But Kirk Douglas' Chuck Tatum, a washed-up reporter desperate for a big story, convinces everyone to take a slower, more dramatic route. The real story unfolds through Wilder's methodical tracking shots of how the rescue site transforms. First come the news trucks. Then the food vendors. Soon there's a Ferris wheel against the desert sky, children eating cotton candy while a man slowly dies underground.

One of the film’s most devastating sequences focuses on the engineer who designed the original rescue plan. In his first scene, he presents a simple solution - dig directly to Leo. Six hours, maximum. But Tatum pulls him aside, frames a more complex plan as an opportunity to showcase "innovative engineering techniques." The engineer's face flinches as greed wrestles with conscience. The camera holds on him just long enough to see conscience lose. By his next scene, he's giving technical interviews to national press, explaining why his complicated solution is the only way forward.

This is where Wilder twists the knife. A full thirty minutes of the film follows different characters discovering "the truth" about Tatum's manipulation. Each revelation becomes a seduction. The deputy sheriff figures it out during a late-night patrol, catching Tatum orchestrating photo ops. Instead of exposing the fraud, he starts coordinating crowd control to maximize media coverage. The local diner owner realizes the truth when he overhears Tatum coaching Leo's wife - but by then his cash register overflows with tourist money. By now, tourists are buying souvenirs of a man's slow death. Vendors are hawking hot dogs while rescuers perform for the cameras. Everyone getting their taste of the action while pretending to care about the tragedy. The real profit comes from letting people feel like savvy players instead of guilty bystanders.

Wilder shoots these revelations like noir confessionals, all harsh shadows and tilted angles. But they're really recruitment scenes. Each new conspirator gets pulled into what Tatum calls "the good seats" - positions of privileged knowledge that feel more valuable than truth itself. A small detail makes this point perfectly: everyone who knows "the real story" starts eating at a private table behind the diner counter. They share knowing looks over coffee while the tourist masses fight for regular seats.

The modern propaganda machine works exactly like Tatum's carnival. Give people inside access to "hidden knowledge" and they'll help you bury the truth while thinking they're excavating it. Every conspiracy theory Facebook group, every extremist pipeline, every radicalization YouTube channel runs on the same code: make people feel smart for being fooled. The game is about feeling like you're clever enough to see through them while spreading them further.

The left keeps trying to expose corruption while the right builds franchises around it. They've turned "doing your own research" into a multi-level marketing scheme where every participant feels like an investigative journalist uncovering deep truths. The product isn't information, isn’t data - it's the feeling of being an insider, a player, someone smart enough to see how the game really works.

Most corruption spreads through FOMO. Tatum's diner counter became power's perfect petri dish - everyone who walked past those "special" tables in the back learned exactly how exclusivity breeds complicity. These weren't just the best seats in the house; they were boxes at the corruption opera, with a perfect view of everyone else standing in line. Wilder knew truth works better as a VIP room than a spotlight. His circus didn't need security because the marks protected their own con, too invested in their roles as inside players to ever break character. Forget exposing corruption - franchise it. Build a members-only club where everyone gets to feel like they're running the biggest game in town, even as the game runs them.

For Democrats, the lesson lands like brass knuckles. Stop treating truth like a weapon of shame. Turn it into a form of privileged access. First, build your back room. Start small - a Discord server where people feel special just for having the link. The diner counter goes digital.

Then layer your access like a Russian nesting doll of bullsh*t. Make getting "inside" feel like levels in a game. Basic membership means you've seen the truth. Silver tier means you help spread it. Gold tier? You get to invent new "truths" for the plebs below. Every level up makes people feel smarter, more important, more invested in maintaining the whole pyramid of lies.

Tatum's carnival worked because everyone got a piece of the action but no one got enough to feel satisfied. The engineer tasted fame but wanted fortune. The sheriff grabbed local power but dreamed of national office. The hot dog guy made bank but imagined becoming the next carnival king. Keep them hungry. Keep them climbing. Make them think the real prizes wait just one level up.

The epilogue (Or: How I’ve probably lost it)

When I tell people I'm writing a Machiavellian playbook for Democrats from old movies, they think I've finally lost it. But Andy Griffith hawking fascism-flavored vitamins in "A Face in the Crowd" just gets it in a way that none of my fancy poli-sci professors ever did. While they were teaching theory, Hollywood's best villains were running a masterclass in how power actually works.

My Google searches now think I'm planning a coup, which I guess is technically true if you count "saving American democracy with tips from cinematic sociopaths" as suspicious behavior. But between Rhodes selling outrage like snake oil, Christensen turning mental breakdowns into prime time gold, and Tatum franchising corruption like it's a McDonald's - they've given us better tools than any campaign strategist's PowerPoint ever could.

These old films knew something we forgot. Power doesn't speak the language of policy papers. It speaks pure showbiz, baby. So let’s start taking notes for 2028.

P.S. Apparently hitting that little heart button is the equivalent of leaving a good tip for the algorithm™ gods. So if you enjoyed this essay, please give it a like. And if you're sharing any of these takes in the wild (bless you), tag me - I love seeing which parts made you go "YES FINALLY SOMEONE SAID IT." Sharing is also deeply appreciated because, you know, sharing is caring and all that cinema-loving jazz.

German film director Dennis Gansel and Rat Pack Filmproduktion premiered their update version of the Wave story “Die Welle” at the Sundance Film Festival on January 18, 2008 (Jones/Neel/Hancock attended). It places the story in a present day German high school, and is a modern take on the story. Original Third Wave teacher Ron Jones has a brief cameo appearance in the film (sitting at a restaurant table during the town tagging sequence). Ron also appears in the German DVD extras, visiting the set during filming.

Your writing is a revelation.

Though I disagree with some of the opinions expressed here (we're allowed, I'm not going to unfriend Sophie (lol)) you've illuminated here why art needs to be understood by political types.

In my own experience in journalism, political writers tend to look down on elements of culture like cinema. It's about who has the best narrative and the Dems lost on narrative. These are useful reflections, but if there's a general lack of nuance in most film crit, it's a hundred thousand times worse in politics. It's been interesting but also discouraging to observe as an outsider. It differs from pundit to pundit but the lack of artistic/cultural awareness is bad.

We expect our politicians to know something of history, and we should expect them to know the arts.