congratulations you have permission to watch everything wrong in 2025

Because someone needs to tell you it's okay to break every viewing rule that exists.

My partner started watching Harry Potter with Deathly Hallows Part 2.

The revelation happened while making carbonara. Between stirring pasta and crumbling pancetta, he mentioned how much more electric Voldemort's final duel felt when it served as his introduction to the series. My hands froze mid-pancetta-crumble. The pasta water bubbled over in protest. Starting with the climactic battle at Hogwarts meant only one thing - this beautiful madman had decided to experience the entire series in reverse.

"You started with the ending?" I asked, trying to process this rebellion. He nodded, continuing to grate parmesan with infuriating nonchalance, as if he hadn't just admitted to watching one of the most meticulously plotted film series backward - like walking through the Great Hall from graduation day to sorting ceremony.

His disregard for proper viewing order feels especially radical in 2025, when streaming platforms have turned entertainment into pure commodity. Netflix's "Play Something" button and recommendation algorithm feel like surrender flags from a company that knows we're barely paying attention. They've even started designing content specifically for distraction - uniform, safe programming that former producer

describes as instantly recognizable: "Oh, look at those two couples kissing. One's wearing pool flippers. That must be a romantic comedy." The victory isn't in making something good - it's in making something that keeps you subscribed.We've reached two simultaneous yet opposite crises in how we consume stories: either we're treating them like homework that requires rigid rules and proper order, or we're so checked out that entertainment has become background noise for our scrolling. We're all trying to be the valedictorian of pop culture - dutifully making our way through canonical watchlists, saving arthouse films for when we're "ready" (like they're fine wines that might spoil if opened too soon), treating entertainment like a graduate thesis we need to defend. Watch in order. No skipping episodes. Avoid spoilers at all costs. God forbid you admit you've never seen The Wire - the pearls, they will be clutched.

My partner's accidental viewing anarchy made me question everything I thought I knew about experiencing stories. As he proclaimed, there's a particular joy in breaking the unwritten laws of watching things "properly." Like discovering that eating dessert first doesn't actually ruin dinner - it just makes you appreciate the sugar rush differently.

So here's your 2025 permission slip to watch things wrong. To skip the boring episodes, to start with the ending, to mix up the timeline until it barely resembles the original. Because sometimes looking at something sideways lets you see it straight on for the first time.

Permission #1: You can start with the ending

The best part about watching The Matrix Resurrections before any other Matrix film? That moment when you realize you've been experiencing the exact same confusion about reality as Neo. Every reference feels like a prophecy. Every callback becomes a mystery. You're not just watching someone question their reality - you're living it. The whole "there is no spoon" thing hits different when you have no idea why there isn't a spoon in the first place.

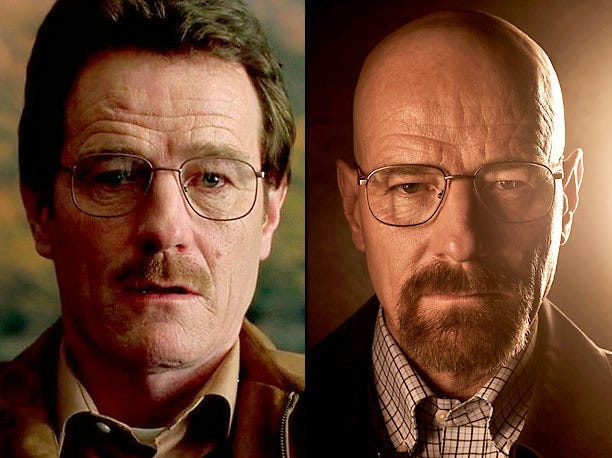

Remember when AMC used to market Breaking Bad as "Mr. Chips becomes Scarface"? They got it backwards. Start with "Ozymandias" - watch the empire crumble before you see its foundation. Suddenly Walter White's journey transforms from a steady descent into darkness into something far more unsettling: a man reverse-engineering his own destruction. Each earlier episode becomes a breadcrumb leading not forward to his downfall, but backward to the moment he convinced himself he could control chaos.

This backwards alchemy works precisely because we've been trained to view stories as rigid exercises in proper progression. Netflix wants characters to narrate their own actions like confused tour guides. Meanwhile, Mad Men's finale - Don Draper finding enlightenment and a Coke commercial at a California meditation retreat - becomes absolutely unhinged as your entry point. Every previous moment of Don straightening his tie or charming a client illuminates not who he'll become, but who he's desperately trying to escape.

The whole "watching things in order" doctrine feels like those people who insist you need to read James Joyce's entire bibliography before touching Ulysses. As if stories were math equations that only work when solved in the proper sequence. But narratives aren't instruction manuals - they're kaleidoscopes. Sometimes you need to turn them upside down to see all the patterns hidden inside.

Permission #2: You can watch only the parts you want

I watched every Paris Geller episode of Gilmore Girls and skipped the rest. This feels like admitting to a crime in certain circles, like telling a sommelier you drink wine through a crazy straw. But I got exactly what I needed from Stars Hollow. A hyper-concentrated shot of pure overachiever energy, stripped of all those saccharine coffee shop scenes.

The cinematic universe doesn't collapse when you abandon ship halfway through. My life got measurably better after deciding Inception ends when the top starts wobbling (and that’s coming from someone who’s obsessed with endings). The last season of Game of Thrones exists in a quantum state on my hard drive - watched once but at large forgotten, like Schrödinger's disappointment waiting to be unveiled (and that’s a marketing campaign I had to work on).

And those sacred-text filmographies that Film Twitter used to pester you about? No one's checking your homework. You can skip straight to Wong Kar-wai's In the Mood for Love without watching his entire back catalog. Start with Mulholland Drive and let the rest of Lynch's work exist as gorgeous possibilities. The cinema police won't break down your door if you decide Reservoir Dogs is the only Tarantino you need.

Maybe the real artistry is found in knowing when to walk away. In cherry-picking the moments that actually matter to you instead of trudging through every minute of so-called required viewing like some cinematic martyr. The only person who needs to appreciate your viewing choices is you - and possibly that one character who makes the whole thing worth watching.

Just ask Paris Geller.

Permission #3: You can give things half a chance

I lasted exactly three episodes of Dune: Prophecy before accepting defeat. The whole time I kept thinking: I love HBO. I love science fiction. I even love watching people have tense conversations in dimly lit rooms. And yet, every minute felt like being trapped in a very expensive, very beige waiting room where everyone speaks in whispers about space politics.

The streaming model has perfected this kind of slipshod filmmaking, designed for an audience they assume is barely paying attention. Several screenwriters claim Netflix executives routinely tell their writers to "have characters announce what they're doing so viewers who have the program on in the background can follow along."

This background-noise approach to content hasn't stopped the streaming era from turning entertainment into endurance sport however. We're all competing in some imaginary marathon where finishing every show in our queue equals cultural victory. Dropping a show mid-season now carries the same weight as leaving a party without saying goodbye - a social faux pas that demands explanation. But here's the thing about marathons - even professional runners know when to sit one out.

You can give something an honest chance without committing to a long-term relationship with your sofa. Watch a few episodes. See if it clicks. If it doesn't, move on. The algorithm will suggest something else, the group chat will survive without your hot takes, and life will continue its regularly scheduled programming. This isn't about avoiding things outside your comfort zone or dismissing shows before they "get good." It's about recognizing the difference between challenging art that rewards patience and ‘content’ you're only watching because everyone else seems to be watching it too.

Every hour spent forcing yourself through a show you're not enjoying is an hour you could spend discovering something you might love. Or learning to make soufflé. Or finally organizing your Google Drive folders. Or literally anything else that doesn't make you check how many minutes are left in an episode.

Besides, you can always read the Wikipedia summary if you need to know how it ends.

Permission #4: You can let art hit you where it hurts

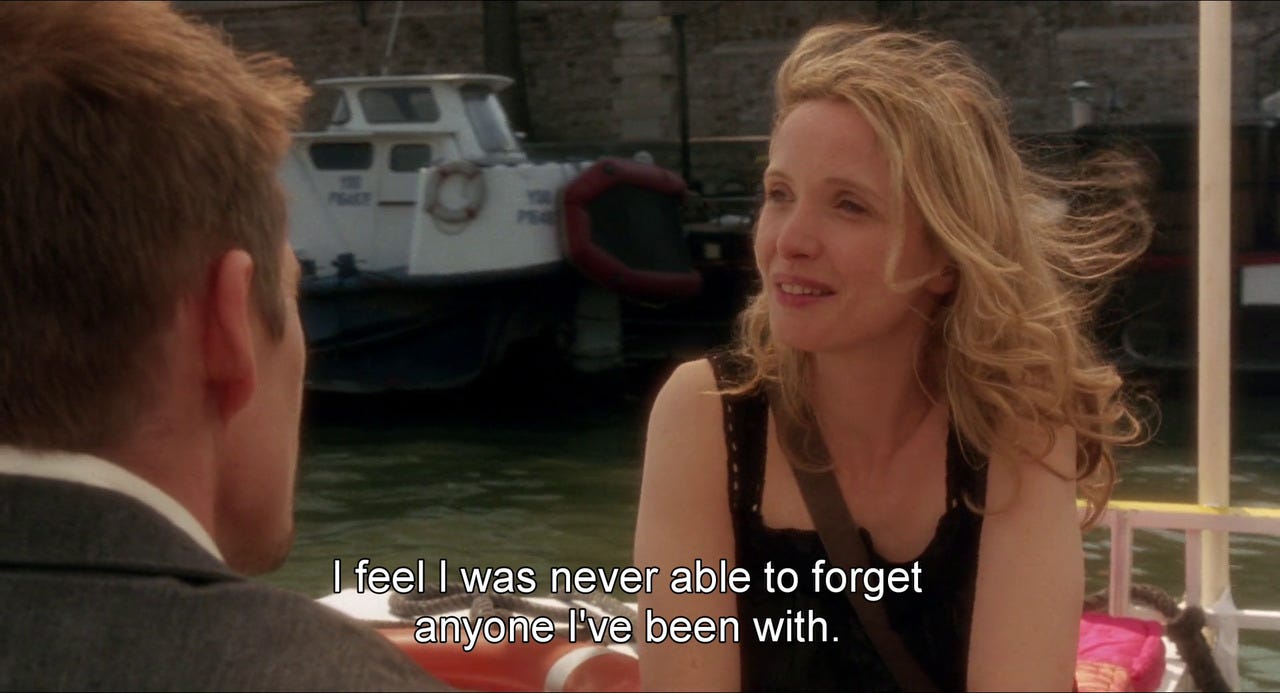

The best film criticism I've ever written came from rewatching Before Sunset during a summer storm in Athens. Rain hammering against windows while Jesse and Celine walked through sun-drenched Paris. Lightning illuminating my notebook where I'd scrawled "THE BOAT SCENE - WHY DOES IT HURT LIKE THIS?". Not exactly Cahiers du Cinéma material, but infinitely more honest than pretending I only cared about the tracking shots.

Here's your permission to stop pretending you're above getting personally wrecked by art. To admit that yes, you've memorized that monologue about love being "about damage control" not because you're studying screenplay structure, but because it articulates something you've never been able to put into words. To acknowledge that certain films live in your bones, not just your brain.

We've created this bizarre separation between appreciating art and feeling it. Being moved by something does not make your engagement less valid. Relating too deeply to Celine's fear of missing life's big moments does not mean you’re not paying enough attention to the film's commentary on American imperialism or whatever.

This is your permission slip to let art matter on a cellular level. You can circle the scenes that gut you. You can write embarrassingly earnest notes in the margins. You can let yourself get lost in the moment before dissecting how it was constructed. The algorithms want us to consume films and television in neat categories - "prestige drama" or "comfort watch." But the most electric cinema lives in that messy space between appreciation and pure feeling. The sun keeps setting in Celine's apartment. Nina Simone keeps singing about truth. Jesse keeps missing his plane. Some scenes deserve to be felt before they're dissected.

Permission #5: You can have ‘inconsistent’ taste

The film critic who told me years ago I couldn't possibly appreciate Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles if I also loved Magic Mike XXL can cordially get bent. He delivered this verdict at a panel about "serious cinema," adjusting his tortoiseshell glasses with the gravitas of someone about to explain why fast cutting is killing culture. The cultural hierarchy needed maintenance, apparently, and he'd volunteered for the job.

Film criticism spent decades building walls between what counts as legitimate cinema and what gets dismissed as mere entertainment. The sacred and the profane, filed away in their proper little boxes like a film snob's taxonomy of worth. Pauline Kael got dragged for daring to suggest that trash cinema might have vital energy that self-serious art films sometimes lack. The audacity of finding value in both Brian De Palma's sleaze and Bergman's existential crisis.

“Movies are so rarely great art that if we cannot appreciate great trash we have very little reason to be interested in them.”

- Pauline Kael

But 2025 belongs to the omnivores. To the viewers who understand that Douglas Sirk's melodramas have more to say about American excess than most prestige pictures. Who can trace the line from German Expressionism through Tim Burton straight to the latest superhero spectacle without having an aneurysm about the death of cinema.

Your viewing passport no longer requires consistency. Cross those borders. Ignore the guards. The same eyes that weep through Ozu can sparkle at Step Up 2: The Streets. The brain that processes Tarkovsky's long takes can also appreciate the precise timing of a Sandra Bullock pratfall.

The only bad taste is pretending you only have one kind of taste. The rest is cinema.

The French New Wave started because some film critics got bored with rules and decided to break everything. They turned their cameras into the sun. They jumped through time. They made Jean-Paul Belmondo talk directly to the audience. Fifty years later, we're still arguing about proper viewing etiquette while missing the point entirely. Cinema thrives on revolution, not regulation.

So take these viewing permissions and make them your own. Watch the ending first. Mix high art with high camp. Skip the boring parts. Let art break your heart. And if anyone questions your choices, just tell them you're conducting an elaborate viewing experiment. They can't argue with science.

P.S. Apparently hitting that little heart button is the equivalent of leaving a good tip for the Substack feed™ gods. So if you enjoyed reading this, please give it a like.

A final note for people with taste 🫦

While the internet's prioritizing hot takes and SEO-optimized nothingness, I’m trying to building something genuine with this newsletter: a sanctuary for people who believe film and television criticism can be thoughtful, accessible and fun all at once.

For the price of a truly mediocre sandwich, consider joining the resistance with a paid subscription – it keeps independent film writing alive and the algorithms at bay.

Plus, you'll get exclusive access to After Credits, my monthly handpicked selection of films & tv shows that will make your brain do the happy chemicals AND save you from doom-scrolling.

Now go forth and raise those standards, darling.

- Sophie x

Goddamn, yes, this has been my approach to media/art for a long time. Back in the days of network tv (yeah, yeah, I's old) you just tuned into whatever was on, at whichever point it was on. 20 minutes into a movie, 50 minutes in, maybe it was the third in a series, who even knew? You turned it on and just started watching, because that's what was on. And holy shit did we all fall in love with so many movies and shows via this method. Often because they came across as vastly more intriguing than they actually were. What did that line mean? Who was that specific character? When I would finally watch the whole movie all the way through, most of these gripping moments turned out to have been boringly setup in the parts I missed, nothing mysterious about it at all.

This was true for shows, too - what episode was this? What season? You didn't freaking know, you just tuned in and experienced it.

As a lifelong comic book reader this was something I was groomed for - Fantastic Four issue #242 is on the spinner rack at the grocery store? Well, that's what you were reading. God knows if you'd ever tumble upon #243 a month later or any of the ones before it.

I'm always baffled when people "complain" that they have to watch every Marvel Cinematic everything just to follow the uber-plot. Like they might not realize one character who shows up in one scene was actually introduced in some other tv show or movie. My god, who cares. It doesn't actually keep you from understanding the essentials, or even most of the minutiae.

To this day, I never binge watch anything. I watch most movies in 2-3 sittings. And sometimes, I still love fast forwarding 20 minutes in first, just to see how it plays. Keep the mystery of storytelling alive! And don't make it a job, ffs.

I feel like the James Joyce in order thing comes from when people who start with Finnegans Wake or whatever are like "You can't convince me this dude writes regular, meaningful prose" so it's like, "Look, if you start from Dubliners and go from there you will very clearly see the development from canny regular prose to uncanny experimental art." So it just became a way to do it logistically.

Some of your points remind me of this great line from a rom-com script a friend of mine wrote, where a guy always watches only the beginning and end of When Harry Met Sally because "I don't like the scenes where they argue."

I do love your idea of starting a person with Matrix Resurrections to indulge in the disorientation of it.

And Breaking Bad is a great point too. First (linear) watch thru you're like "Oh no we're watching Walt lose his soul!" Second watch thru you're like "Holy fuck this guy was cracked from the beginning." The actual murders start much earlier than it feels. So you can skip the first watch effect if you start at the end.

One thing I was glad to give up in cinephilia ages ago was the feeling like I "need" to see anything in particular. This goes for canonical classics ("You haven't seen Glengarry Glen Ross??!"), event franchise releases ("Yeah but how do you know you won't like it if you don't watch it?"), or awards season slurry ("But what was your opinion on The Green Book?").

I learned from writing reviews in college that sometimes you get "coverage brain" where you not only feel you have to keep up with the most significant whatever focus (so like recent releases, recent indie releases, briefly I got paid for Japanese movies reviews and felt like I needed to cover every mentionable jedaigeki), but you also feel like you have to perceive the movie in a particularly critical or insightful way. And whereas that can help you to some degree learn how to think of your own taste and values, after a certain point it makes watching a movie a procedure rather than an experience, and for a lot of types of movies that kills the value.

Genuinely speaking, if I was still reviewing movies like I did on IMDb all those years ago, I probably would have hated I Saw the TV Glow. It is NOT plotted well. But it's my favorite movie of the year, because its universe reflects people I once knew. Coverage brain would have killed that for me.