bridget jones and the dying art of being a loser

Or what Bridget Jones' burnt pasta tells us about performative loserdom.

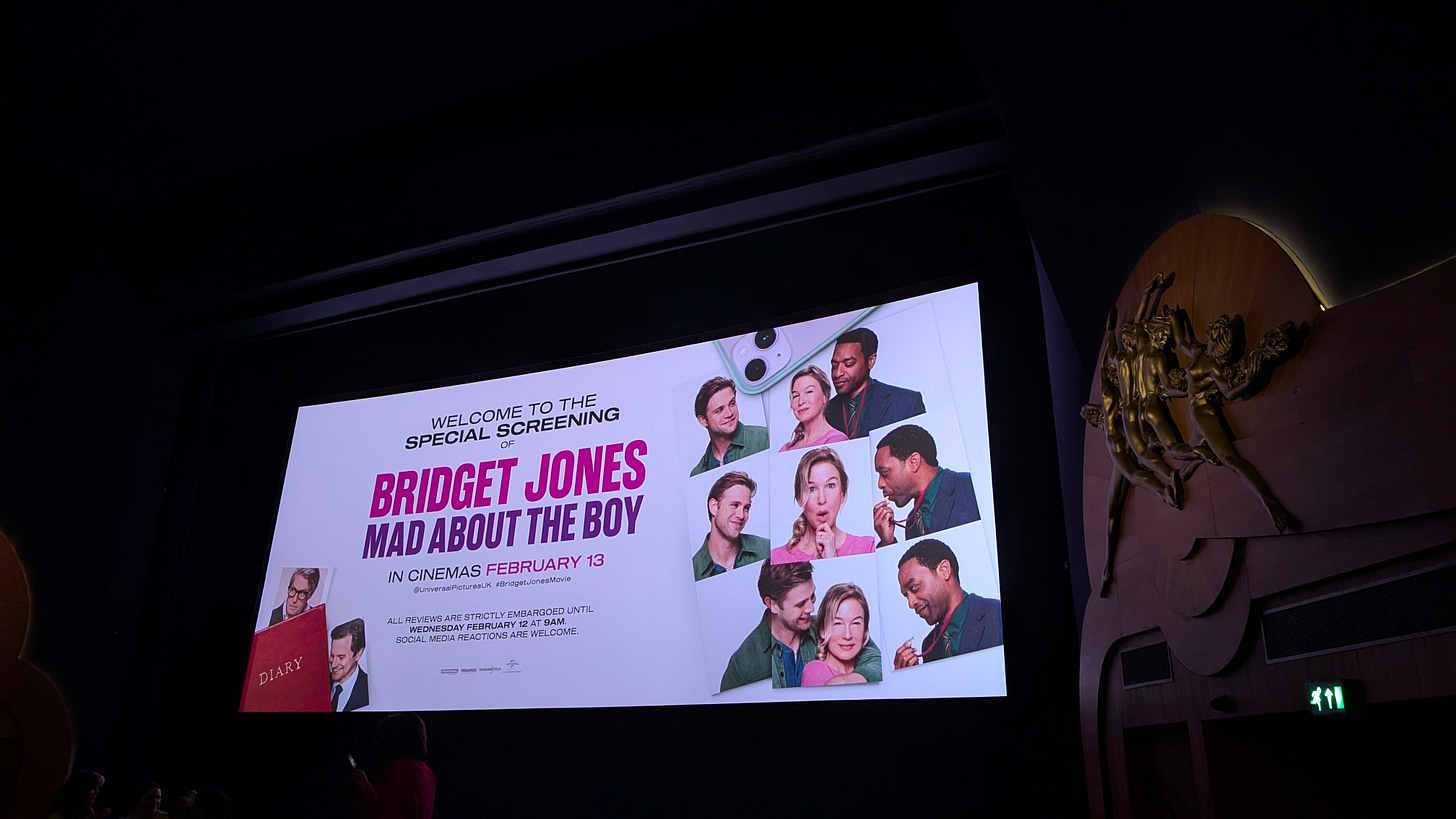

I spent last week drinking wine and rewatching the Bridget Jones franchise after seeing Mad About the Boy at a press screening. The new film stars Chiwetel Ejiofor's abs and finds Bridget at 51, a widow juggling motherhood, a love life, and a career while single-handedly raising two children. The premise sounds like a 30 Rock parody until you're watching it unfold, at which point it transforms into something far more unsettling: a mirror reflecting the slow, agonizing death of our ability to be genuine, actual losers.

My wine-addled brain kept circling back to that dinner party scene from the first film. You know the one. Bridget, alone in her kitchen, staring down at ingredients like they’re inscribed in ancient Sanskrit, radiating the unhinged confidence only achievable when you seriously believe blue soup is the next culinary revolution. The kind of confidence that whispers, “Yeah, this definitely won’t send my guests sprinting to update their living wills while Google-mapping the nearest ER.” Oh, honey, it absolutely will.

But that’s not why it haunted me. It’s because that scene astutely encapsulates what being a “loser” meant back in 2001. Bridget’s obsessive weight calculations, her PhD-level talent for torpedoing professional opportunities, her magnetic attraction to men who treat emotional availability like it’s a highly contagious disease—none of this read as elegantly constructed quirks designed for mass consumption. These were genuine, unadulterated Ls that came with genuine, unadulterated consequences: social exile, career annihilation, the gnawing realization that basic adult competence might forever remain a cruel mirage, shimmering just beyond your grasp, something you’re too damn tired to chase anymore.

I live this shit in my bones. Thirty-two years of my dyspraxic body quietly raging against the machine of physics. Watch me try to carry three things at once during work meetings, my water bottle performing its daily betrayal as I attempt to project competence in front of people who definitely noticed the coffee stain blooming across my shirt.

My dyslexia, on the other hand, makes reading feel like Russian roulette. Fifth grade, standing in front of twenty-three kids who already think I'm…eccentric, watching words scramble and dance while my teacher's mouth gets progressively tighter. High school poetry slam where I had to "start over" four times, with every restart clicking like a tiny bullet in the chamber of my reputation. University seminars spent praying nobody asks me to read the passage out loud. The self-proclaimed "loser" label wasn't some constructed aesthetic. It accreted organically, like moss, over years of verbal missteps and muttered apologies, pursuing me into adulthood with the same unsettling tenacity as the ex who still stalks your Stories.

It's in Mad About the Boy where something shifts. Bridget evolving from chaos vector to chaos whisperer. Past the usual explosions lurks a woman who's learned to wear her mess like armor. I know this dance, the crawl from thinking every fuck-up needed fixing. That just a bit more effort is the answer. Like if we just read enough Judith Butler we'll unlock the secret to soup that doesn't qualify as bioterrorism, or finally understand why that guy who talked about Foucault for four hours at the bar never texted back. Or all those nights squinting at finance blogs thinking THIS would transform us from people who say "stocks" into people who grasp what dividends actually do.

Then suddenly you're thirty-something realizing growth isn't about hammering yourself into someone else's template of success. It's about figuring out which parts of your chaos to keep as battle scars and which ones to finally let rest.

some bodies refuse to win

The early Bridget Jones films capture something about losing that we've lost. I remember one of my favorite scenes, the book launch disaster. Yeah, the one where Bridget showed up in full Playboy regalia while everyone else channeled their inner Ruth Bader Ginsburg. But it wasn’t just the costume that was a total screw up. It was Bridget's diary entry before: sitting in semi-darkness for weekends watching cricket with Daniel's hand down her bra, occasionally mustering a weak "Was that a run?" while dreaming of mini-breaks and riverside picnics in floaty white dresses.

This is Bridget who spends nights kneeling on towels, simultaneously waxing her legs and watching Newsnight, desperately trying to form one coherent opinion about current events. The scene, as you would expect, unfolds like a slow-motion car crash. "Mr. Fitzherbert-Willoughby has taken full responsibility..." she begins, her body going against every social rule she's memorized. The silence that follows fills the room like smoke, punctuated only by the gentle clink of wine glasses. This isn't the kind of failure you package for likes. It's pure uncut social embarassment, the kind that has you counting calories at 4 AM and wondering if your body is somehow getting smaller but denser.

Theory skips right over bodies like mine and Bridget's. Zizek spent his career writing about ideology, those invisible social rules that structure how we move through the world, the ones supposedly running in our mental background like well-behaved software. He talks about how we internalize these rules so deeply we follow them without thinking. Butler pushed this further, arguing that our very identity is built from countless small performances: the way we move, speak, present ourselves, accumulating over time into what looks like a coherent self.

But what happens when your body refuses to run the program?

When it treats every social norm like a suggestion and every performance like improv night? "How can I have put on 3lb since the middle of the night?" Bridget wrote in her diary. "Could food react chemically with other food, double its density and volume, and solidify into ever heavier and denser hard fat?". It is in these moments, where loserdom reveals itself as something beyond performance or counterperformance. It's the body's stubborn insistence on its own reality.

we’re now rehearsing our rock bottom

Sephora is teaching nine-year-olds that being a loser means having fixable skin. Apparently, you’ll now find nine-year-olds on birthday scavenger hunts in their stores, racing between displays of molecular repair serums. "What color is the cap of Drunk Elephant's Lippe Balm?" they chant, not knowing they're being groomed to one day film themselves crying about their pores in front of $300 worth of acid treatments. These kids will grow up to package their skin struggles into perfect three-act structures: the close-up of acne scars (raw vulnerability), the self-care shopping spree (sponsored by Sephora, obviously), and finally the healing journey reveal (filmed in portrait mode). I think about this while trying to remember if I've washed my face today.

This commodification of authenticity reaches its apex in what Maytal Eyal terms "McVulnerability"— that synthetic fast-food version of human emotion that's simultaneously everywhere and nowhere. Her Atlantic piece documents how tears transform from genuine expression into social currency, tracking influencers who pivot seamlessly between sobbing confessionals and supplement sponsorships. Trisha Paytas lives and breathes this type of faux-vulnerability, filming herself watching herself cry in an infinite regression of monetized emotion. When she breaks down over relationships, trauma, or pizza toppings, she's not experiencing vulnerability but she’s perfecting its performance.

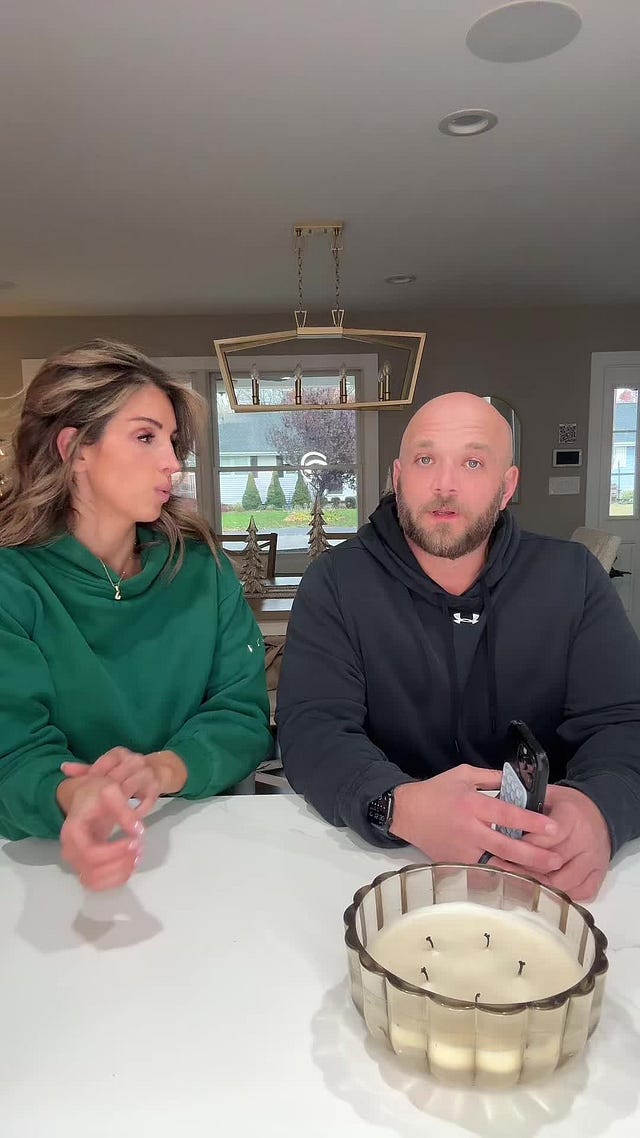

TikTok trends like "We Listen and We Don't Judge" add to the faux-loserdom pile. Two impossibly successful people sit in their kitchen (which looks like Architectural Digest hate-fucked Williams Sonoma) trading confessions about their supposed inadequacies. From this backdrop of Viking appliances and children's artwork arranged by color theory, they confess their struggles: hiding in bathrooms to avoid parental duties, stealing fries from their toddler's meals, pretending to work while actually napping. Their revelations land softly, cushioned by evidence of their fundamental competence: The kitchen declaring "we summer in spaces you couldn't afford to winter in”. The teeth suggesting their orthodontist vacations in St Tropez. The fuck-yeah energy of someone who's never had to beg their bank to extend their overdraft.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Five minutes into Bridget Jones’ Baby, Bridget is face-down in festival mud after attempting to introduce a band. The film presents this glorious failure like a middle finger to the gods of self-improvement. No amount of professional success can vaccinate you against being fundamentally incapable of remaining vertical in public. Some of us simply lost that lottery.

Tell the Bees maps other ways in which we've drifted from Bridget's dedication to public humiliation. "Over the past few years, something has shifted in the perception of acceptable recreational behavior," they write, watching millions transform their bedrooms into metropolitan monasteries. "People are gleeful to admit they have no hobbies, no interests, no verve." A TikTok of someone declaring their mattress their spiritual homeland accumulates 28 million disciples.

Bridget Jones, more often than not unknowingly, has always refused this notion of cultivated inertia. Even when she experiences success, it doesn’t immunize her from being fundamentally impossible to fix. "The culture yearned for Brat Summer because we've been fossilized," Tell the Bees notes.

But Bridget shows up to a christening in what appears to be a wedding dress because her limbic system interprets "appropriate attire" as a personal attack. She’s climbing fences in shoes that cost more than my mortgage but provide approximately the same structural support as wet paper.

She maintains the ideal of someone who hasn't yet discovered they could build a brand around being a loser entirely.

bridget is still losing at 51 (but in new ways)

British cinema's architecture of feminine catastrophe has served us endless iterations of women learning to navigate wine glasses without causing property damage. Now Mad About The Boy ruptures this well maintained ecosystem, forcing a reckoning with what happens when the rom-com heroine outlives her own happily-ever-after.

The streets of London spread beneath Bridget’s feet like a map of everything time refuses to fix. Four years after Mark's death, she still sets pasta ablaze and remains fundamentally unclear on Newton's laws, but these familiar incompetencies have transmuted into a vocabulary of survival. How many times can you read your dead husband's obituary before the words stop making sense? How many parent-teacher conferences can you survive while pretending your world hasn't tilted on its axis?

The reviews paint her as older, sadder but none the wiser but they miss how wisdom sneaks in through the back door while you're busy setting appliances on fire. When twenty-nine-year-old Roxster (I’m sorry I still don’t understand why we’re trying to make Leo Woodwall happen but that’s for a different essay) comes back after ghosting her, the film reveals its true preoccupation. The old Bridget would have turned this into a project of self-actualization. This Bridget simply files him under "survivable disasters" alongside that time she attempted soufflé for the PTA meeting.

"I don't think I'll ever let go of Bridget," Renée Zellweger tells The Hollywood Reporter. This version of Jones measures time differently: not in cigarettes smoked or calories consumed but in how many minutes since she last thought about Mark, how many times she's explained to five-year-old Mabel why Daddy lives in the stars, how many times she’s proudly told Daniel Cleaver to fuck off, how many times she’s nonchalantly showed up in pyjamas during school pick-up, how many times she's managed to feed her children something that wasn't entirely beige.

Indeed, Zellweger argues our Bridget has evolved: "Is she more measured? Probably. Does she have time to worry so much about herself? Not as much. But familiarly, she is concerned about if she's measuring up." Our girl's still counting, sure, just not calories anymore. This time around it’s the small victories that add up to surviving.

Watching the film on the big screen, I sat there, absolutely transfixed, as she prowled through Tinder with the signature Bridget-like delusion. Through back and forth texts with a stranger, all while having a literal barn owl as her backdrop. Bridget radiates such profound conviction in her own fuckability that I found myself screaming into my scarf. Because this is what happens when you let a woman exist beyond the suffocating perimeter of aspirational Mcvulnerability. This version of Bridget prowls through life with the authentic loserdom that makes you want to build altars in its honor.

time doesn’t fix everything (thank god)

My brain interprets deadlines as suggestions. Appointments as abstract art. I’ve never used a to-do list in my life because frankly, I can’t maintain one. The world moves in straight lines while I spiral through time zones of my own dys-creation. Lauren Berlant called this cruel optimism, that state where your attachment to fantasies of "the good life" actively impede our flourishing. In that sense, hope itself becomes a kind of time trap. Every morning I wake up absolutely convinced that this time I'll discover the secret algorithm of functioning adulthood, or that somehow the accumulated weight of being a loser will finally melt into percipience, like pressure turning coal into diamonds (spoiler alert: the pressure just makes more coal).

In The Aftermath of Feminism, Angela McRobbie interprets Bridget Jones's relationship with time as political failure. Her framework positions Bridget's perpetual catastrophes as "infectious girlishness". This reading filters Bridget through what McRobbie terms the "postfeminist masquerade", a performance of emphasized femininity that works to undo feminist gains. The kitchen disasters, the romantic misfortunes, the professional blunders all become evidence of women's voluntary re-submission to patriarchal standards under the guise of "choice." Your inability to quote Kafka? A symptom of internalized oppression rather than admitting to the idea that some forms of being cannot keep up with linear progress altogether.

Yet at 51, Bridget still hasn’t quite mastered the art of winning. The coveted power mum mantle remains beyond her reach. She still gravitates toward emotionally unavailable men. Even the simple task of retrieving her Netflix password confounds her. But rather than recycled plotlines, these traits carry the accumulated weight of a life lived through as, yes, an authentic loser. In the final chapter of Jones, time itself becomes the object of cruel optimism. This is what Berlant might call a "situation", when crisis transcends temporary state and becomes pure ontology.

The critical dismissal of Bridget as post-feminist fantasy ignores this. Katarzyna Smyczynska argues in The World According to Bridget Jones that the franchise "indicates areas in women's lives in which certain inadequacies have not been done away with." But this understates the case. Bridget's inadequacies haven't simply persisted. They've evolved alongside technological and social changes she can barely comprehend. Sure, the medium may be new, but the underlying grammar of loserdom remains unchanged.

This matters especially now, when loserdom itself has become a form of cultural capital. You know the format: Part one: the mascara-streaked confessional. Part two: the rock bottom montage. Part three: the glow-up revelation, soundtracked by that one Lizzo song about being your own soulmate. The comments section performs its assigned role: "I needed this today" and "you're so brave for sharing." Queen shit. We love a healing journey. Link in bio for 20% off BetterHelp.

Many creators monetize vulnerability like any other commodity.

But others film through tears because they've spent weeks alone with postpartum depression, or because they're processing trauma and can’t afford therapy. The real problem isn't creators oversharing but how online platforms compress every messy human experience into neat three-act structures.

making losing less like a chapter and more like the whole damn book

This compression of time serves the same function as theoretical frameworks that try to make disaster meaningful. When we interpret sustained inadequacy as infantilization, we are showing our own investment in progress narratives. Because how post-modern to think time should add up to something more than itself!

Being a loser demands a different relationship with time altogether. It accumulates like sediment in your bones. Like poetry instead of profit. Like those water rings on your parents’ coffee table that refuse to fade even though you've finally learned to use coasters. Time doesn't develop, it deepens. Resonates rather than resolves.

The optimism turns cruel when we convince ourselves that time contains some inherent logic, that our disasters will eventually settle into meaning if we just keep experiencing them long enough, if we just keep better journals, if we just download one more productivity app.

My tolerance for manufactured loserdom vanished somewhere between my third autoimmune diagnosis and watching my late grandma piece herself back together after burying her own daughter. Some forms of truth emerge only through duration. We should feel allowed to inhabit time that promises nothing except its own continuation.

Bridget's consistent inability to master her circumstances isn't regression, resistance, or even particularly interesting rebellion. It's existence in a world that absurdly demands both instant transformation and the perfect preservation of your past self. This doesn't make Bridget a feminist hero or a postfeminist cautionary tale. No. It plainly makes her a document of how time actually operates on lived experience. Or perhaps a reminder that sometimes duration itself is the point.

The market knows how to package a good loser these days. It can sell you rock bottom, sell you rock bottom adjacent, and absolutely sell you the climb back up. But it can't sell you Bridget Jones at 51, still writing diary entries that go nowhere, still making the same mistakes with better phones, still eating burnt toast decades later.

That's the threat, isn't it? Not that we lose, but that we lose to make it mean something. It’s terrifying to think that some of us keep existing in unmarketable time. Because what's scarier than a woman who refuses to be a Before or an After? A woman who's just...During. Indefinitely.

A final note for people with taste 🫦

While the internet's prioritizing hot takes and SEO-optimized nothingness, TFS is trying to build a sanctuary for people who believe film and television criticism can be thoughtful, accessible and fun all at once.

For the price of a truly mediocre sandwich, consider joining the resistance with a paid subscription – it keeps independent film writing alive and the algorithms at bay.

Plus, you'll get exclusive access to After Credits, my monthly handpicked selection of films & tv shows that will make your brain do the happy chemicals AND access to my more personal posts and essays.

Now go forth and raise those standards, darling.

- Sophie x

What's next on the list? What do you think of Mickey 17?

You’re a fantastic writer - I read a lot on film and rarely come across stuff that blends the personal with serious critical engagement this well. Rare professional jealousy, ha! I’m maxed out on new paid subscriptions for the moment but if that changes you’ll be in line! I have also never seen the BJones films which is crazy given that the originals came out when I was in high school/college. Maybe that will be my end-of-February comfort binge because I really need one!